A version of this story originally appeared on OceanBites

Conservationists can't tackle all of the ocean's problems at once, so scientists are helping them triage

The ocean contains many vulnerable ecosystems that need protecting. So where should we start?

The word triage, derived from the French trier, "to separate out," entered the English lexicon during World War I, when the Brittish found themselves fighting alongside the French. The four-year struggle ravaged Europe, leaving over 20 million soldiers injured and at least 8 million dead. Ironically, the French may have first used the term in the 1800s during the Napoleonic Wars, when they fought against the United Kingdom. In everyday civilian life, medical triage is still used in hospital emergency rooms and acute emergencies where medical professionals with limited resources need to rapidly assess the needs of many patients. Despite its flaws, the triage system strives for the best overall healthcare outcome by prioritizing treatment of the most vulnerable.

Ecosystems as Casualties

In a sense, human-driven global warming has declared war on the world’s ecosystems, and the casualty of this war is biological diversity. On land, the increasing occurrence of wildfires is interrupting natural cycles of habitat recovery, making forests and grasslands less hospitable to life. At the poles, ice melt is driving animals that live on ice shelves to extinction, while the accompanying sea level rise is reshaping the world’s coastlines. In the ocean, increasing seawater temperatures are killing off coral reefs that support the most species-rich ecosystems on the planet.

.jpg)

Bleached coral on the Great Barrier Reef in Australia.

"Bleached coral (24577819729)" by Oregon State University

At the same time, humans are fishing, hunting, mining, drilling, and otherwise exploiting these very same ecosystems. Like the doctor on the battlefield or the nurse in the emergency room, conservationists face the dilemma of triaging efforts to ameliorate the environmental one-two punch posed to ecosystems by climate change and direct human exploitation.

In one of the first studies of its kind, a multinational team of scientists hailing from institutions in Spain, New Zealand, and Australia looked at the dual impacts of climate change and overfishing. Their findings provide a framework for prioritizing marine conservation efforts.

Mapping Diversity and Impact

Coral reefs, which cover less than one-tenth of the ocean floor, but are estimated to harbor upwards of a quarter of marine species, are among the most biologically diverse habitats on earth. They are rivaled only by terrestrial rainforests. Reefs support ‘ecosystem services,’ a term used to describe the resources they provide to humans. Some ecosystem services provided by coral reefs include fish populations, erosion control, and disinfection. Fish are part of a larger picture of biological diversity, but as predators their abundance can be used as a proxy for diversity in reefs. As a result, scientists can use fish populations to understand the health of complex coral reef ecosystems found in the tropics.

But global fish populations don't just fluctuate based on reef health. They're also facing unprecedented pressures from hyper-efficient modern commercial fishing operations. It's impossible to stall the the multi-billion dollar commercial fishing industry, so lead scientist Francisco Ramírez and his colleagues focused their efforts on hotspots of biological diversity particularly susceptible to commercial fishing. They hoped to identify the marine habitats most affected by both global warming and commercial fisheries, helping conservationists prioritize interventions in these most vulnerable locations.

To find these locations, Ramirez an his team had to collect and combine multiple types of data: the biodiversity of ocean habitats, historical ocean warming records, and historical fishing records.

To determine the areas with the highest occurrence of the largest number of species—the greatest biodiversity—Ramírez and co-workers mapped the global distributions of over two-thousand marine species, including mammals, birds, and fish. They then used this data to create a convenient index that could be used to compare the biodiversity of the world’s oceans.

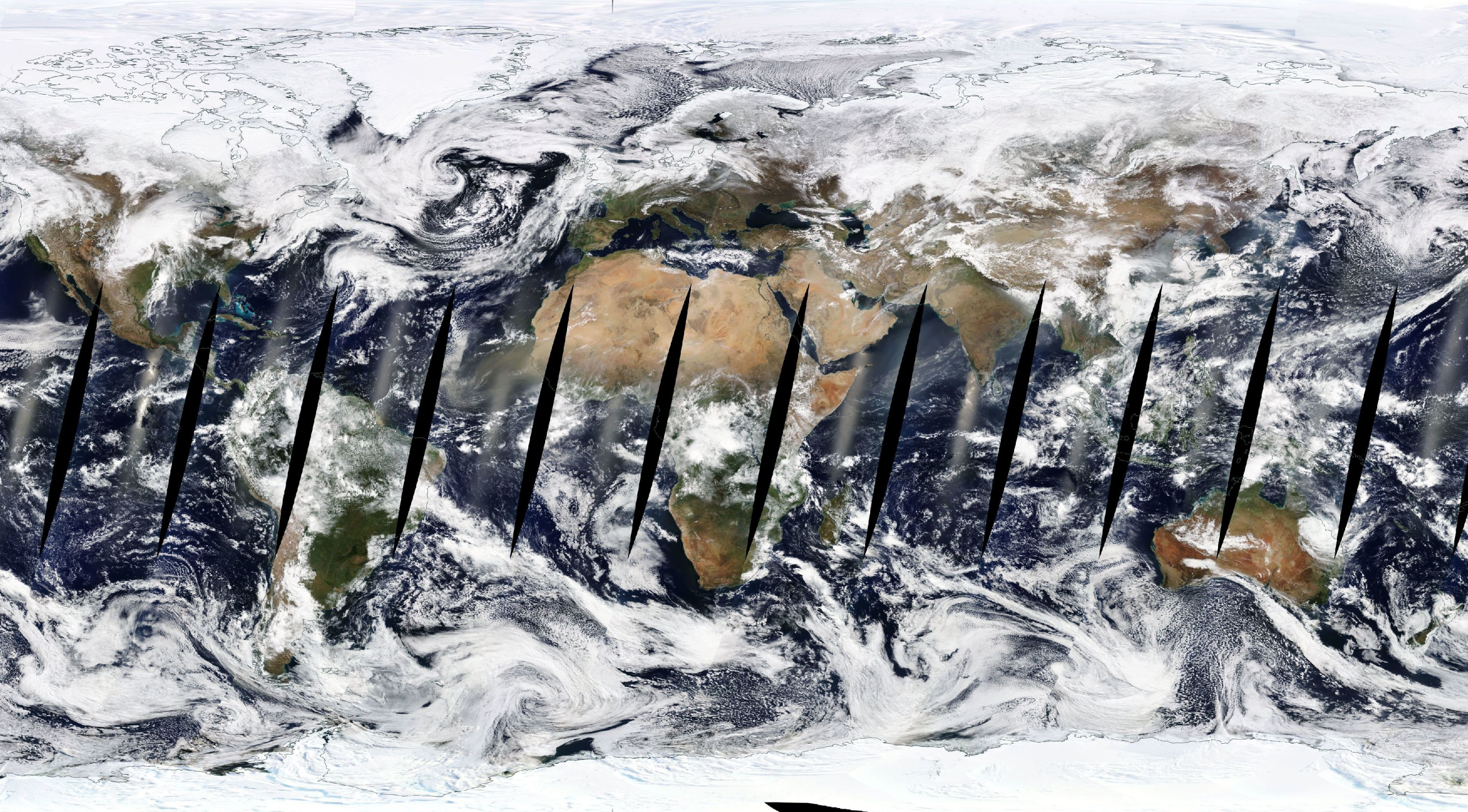

The team next sought to assess how particular ecosystems might have been affected by the dual impacts of climate change and commercial fishing. To look at climate change, Ramirez and his colleagues curated three decades of satellite images, constructing a kind of stop motion animation documenting changes in ocean currents, sea water temperatures, and levels of photosynthesis by tiny plankton that form the foundation of the marine food chain.

NASA Earth Observing System Data and Information System (EOSDIS) data on NASA Worldview provides the capability to interactively browse and layer satellite imagery and data. You can observe the entire Earth as it looks during specific times and dates. Similar data was used to create animated timelines of ocean currents in this research.

Static image from interactive NASA Worldview

Then, the team focused on fishing, overlaying satellite observations with fishing records collected since by commercial fishermen, which provide a rough picture of changes in ecosystem composition over time.

As with biodiversity, the researchers combined all of this data into a convenient index that combined seawater temperature, plankton photosynthesis, and changes in ocean circulation to compare the cumulative environmental impacts in specific locations.

Hotspots of Climate Change Impact

Ramírez and colleagues noticed a few interesting things. They saw a general warming trend in the world's oceans and a corresponding deceleration of the huge current (a.k.a. the “thermohaline current”) that connects the world’s oceans, resulting in changes in transport of cooler waters and nutrients around the world’s oceans.

But they found that the effects of these wider trends weren't evenly distributed. Some ecosystems were deeply impacted, while others seemed to be going about their business as usual. Unfortunately, many of the areas most affected by warming coincided with hotspots of marine biodiversity. Worse still, by examining over half a century of fisheries data, the team found that the areas most vulnerable to climate change were also some of the most overfished waters.

These findings lead Ramírez and his team to identify what they believe to be the six most vulnerable marine ecosystems – the places where the highest biodiversity coincides with largest environmental and fishing impacts. These hot spots include some of the most productive waters on Earth, falling mostly in the warmer waters of the southern hemisphere and including areas in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans.

1. The westernmost vulnerable area includes the central-western Pacific waters of Peru and the Galápagos Archipelago.

“Galapagos sea lion, underwater, up close”

Photo by Derek Keats via Flickr

2. In the southwestern Atlantic Ocean, a marine hot spot occurs in the Patagonian waters of Argentina and Uruguay.

"Sea lions on the rocks at Cabo Polonio, Uruguay, 2005"

Photo by Kenspuss via Wikimedia Commons

3. The coasts of South Africa, Mozambique, Tanzania, Kenya, and Madagascar were included in a hot spot at the western side of the Indian Ocean.

This is the shell of the sea snail 'Turbo imperialis' collected near Toliara (Tulear), Madagascar.

Photo by JialiangGao via Wikimedia Commons

4. In the central-western Pacific Ocean, a large area including water masses surrounding Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Taiwan, and the south of Japan was grouped into one single hot spot.

"School of Pterocaesio chrysozona in Papua New Guinea"

5. Waters surrounding New Zealand and Eastern and Southern Australia were considered the fifth hot spot at the southwestern Pacific.

"Sea at West Coast, New Zealand"

Photo by Ulrich Lange via Wikimedia Commons

6. The sixth hot spot included marine areas in Oceania and the central Pacific Ocean.

Thousands of species of jellyfish like this species of box jelly can be found amongst the diversity of flora and fauna in this hotspot.

While the researchers were able to identify the areas conservationists should focus on first, it won't be easy. Many of the most vulnerable ecosystems exist in sovereign waters governed by a particular country. Multi-national conservation efforts will be necessary to reverse the trend of ecosystem destruction due exploitation of habitats already impacted by climate change. Saving these particularly delicate regions will require collaborative, sustained efforts. Studies like this one that help conservationists triage and focus their efforts are a good place to begin.

Featured Paper

- Ramírez, F., Afán, I., Davis, L. S., & Chiaradia, A. (2017). Climate impacts on global hot spots of marine biodiversity. Science Advances, 3(2), e1601198. http://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1601198