Photo by Pierre Acobas on Unsplash

A proposal to use CRISPR to prevent opioid overdoses is a useless approach to healthcare

Genetically engineering users' brains is short-sighted, reactive, and unnecessary

SARS-CoV-2 has swept us indoors and laid bare the social inequities in the American healthcare system. In many places, Black, Latino, and Indigenous people have been disproportionately infected by the virus. With a greater, global focus on public health, the pandemic's severity may have been reduced. America’s retroactive approach to medicine has failed again.

But another illness has already been testing our healthcare system. It, too, can trace its growth through discordant, half-assed measures. It, too, has highlighted the social inequities in the American healthcare system. But it will persist long after SARS-CoV-2 is beaten.

According to the CDC, about 47,000 Americans died from an opioid overdose in 2018, a number that remained steady from the previous year. This is despite more than $9 billion in federal grants to states, largely for "medication-assisted treatment", over the last three years.

Craig Stevens, a professor of pharmacology at Oklahoma State University, outlined a proposal to prevent opioid overdose deaths by “turning off” a specific receptor for opioids in the brain. I first read his plan in an article for The Conversation, but Stevens also published this idea in a peer-reviewed article for the Journal of Neuroscience Research in May.

Stevens advocates for the genetic alteration of people struggling with opioid addiction by injecting CRISPR molecules into the brain via “a new neurosurgical microinjection technique.” The injected CRISPR molecules would render the mu opioid receptor nonfunctional in specific neurons. In this way, death by overdose — which is caused by slowed or impaired breathing — could be prevented. Opioid addiction, however, would persist.

Any treatment that claims it can save nearly 50,000 lives a year is worthy of our attention. But I take issue with this proposal because it reinforces America's long history of treating national medical crises — AIDS, SARS-CoV-2, mental health — reactively, rather than proactively, and on an individual, rather than societal, level. This approach has failed every time. The opioid epidemic is no different.

From a scientific perspective, Stevens’s proposal isn’t that far-fetched. In mice, deletion of the mu receptor in specific neurons prevented respiratory depression, or slowed breathing, even when opioids were given at high doses. In August, scientists at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, in Shanghai, also published a pre-print showing that CRISPR can mutate specific genes in the brains of adolescent rhesus monkeys.

“Yes, CRISPR-based therapies could technically be delivered in vivo to specifically delete a gene in the human brain,” said Randall Platt, an assistant professor at ETH Zurich, in Switzerland. But, he acknowledged, “substantial work on the clinical development front needs to be done before this would be advisable.”

Specifically, researchers will first need to find a way to prevent off-target effects — unintended changes in the genome — when editing a gene with CRISPR. Platt, who was among the first to use CRISPR to genetically edit genes in the brain of a mouse, told me that “there is absolutely no way to avoid these with 100% certainty.” Off-target effects were present in the so-called “CRISPR babies” that attracted international condemnation in late 2018, with as-yet unknown consequences.

Even though current technologies are not always perfectly precise, genetic engineering is being tested as a treatment for several diseases. There are clinical trials under way to correct Hunter syndrome, which is the first disease to be treated with in-body genetic editing, and to cure sickle cell disease by removing cells from a patient, editing a gene in those cells, and then placing them back into the body. CRISPR components directly injected into the retina are also being tested as a treatment for Leber Congenital Amaurosis, a form of inherited blindness. Genetic diseases, after all, may warrant genetic solutions.

Stevens is advocating for a research direction, not an urgent clinical intervention. Still, the cause of the opioid epidemic is not genetics: it is societal and healthcare shortcomings. Those are things CRISPR cannot fix.

The U.S. spends just 2.5% of its healthcare budget on public health. But the NIH, in 2016, spent more than half of its $26 billion budget on research directly “linked to search terms that include gene, genome, stem cells or regenerative medicine,” according to Erik Parens, a senior research scholar at The Hastings Center.

But the NIH may be changing their priorities when it comes to opioid addiction. The NIH HEAL (Helping to End Addiction Long-Term) initiative spent more than $945 million in 2019. This money includes funding for experimental treatments for opioid overdose, including a putative heroin vaccine and a sustained release implant of Naltrexone, a medication that helps patients avoid relapse into opioid dependence.

While these treatments sound promising, there are already ample tools to treat both opioid addiction and overdoses. In 2018, the entire European Union, including Norway and Turkey, saw fewer than 9,000 “drug-induced deaths.” France, which has one of the lowest rates of overdose-related deaths in Europe, has hundreds of harm reduction centers that provide needle exchange programs and access to social workers and psychiatrists.

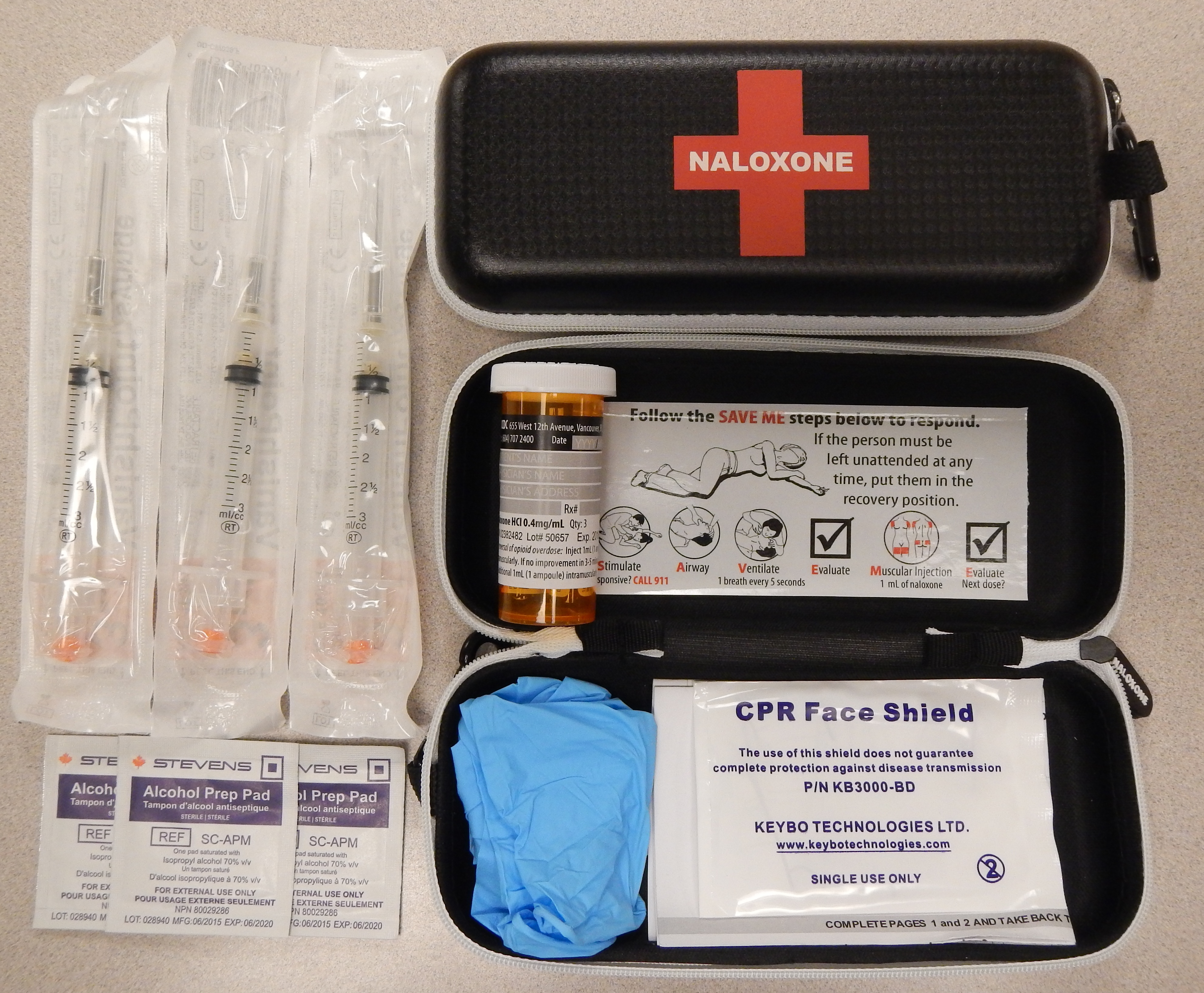

Europe relies on social interventions to treat opioid addiction, and these same interventions can be implemented in the U.S. A study on overdose prevention in Skid Row in Los Angeles found that training people how to use Narcan — which can reverse the effects of an overdose — is a first step to treating overdoses. In a one-hour training session, participants were taught how to spot an overdose, call emergency services, and administer Narcan. Twenty-two of those participants would later respond to thirty-five overdoses, potentially saving dozens of lives.

A naloxone kit

Via Wikimedia

To learn what else could be done to treat opioid addiction in the U.S., I spoke with Lisa Parker, the director of the Center for Bioethics & Health Law at the University of Pittsburgh. When I set up that phone call, I didn’t mention Stevens’s article by name; I merely said that I was writing an op-ed on genetic engineering and the opioid epidemic. But my omission didn’t matter — when I got on the phone with Parker, she immediately said, “I assume you’re referring to this article in The Conversation.”

Parker studies informed consent, gene editing technologies, and opioid overdose risk factors. “What I’m working on is more social interventions,” she said. “My own view is that, for most health-related issues, intervening in social factors is often a better approach, or the first approach, to attempt prior to intervening in the genome.”

As a research program, Parker agrees that Stevens’s proposal is interesting, but argues that prior to therapies involving the genome, we should intervene on a social level.

“I think it is an example of a tendency that we have to look to individuals, and to individual level risks and individual level solutions, rather than looking to the messier, more-complicated social level.”

When I asked Parker what, specifically, could be done to treat opioid addictions on a societal level, she pointed to numerous changes; more follow-ups with patients, altered prescription practices to ensure that people with either pain or substance use disorders get treated for their condition, and wider access and training for Narcan.

“We have a lot of things that we know work to reduce risk of death from overdose, reduce overdoses, and reduce opioid addiction,” said Parker. “We just aren’t adequately doing them.”

These proposals deal with opioid addiction at a community level and will demand radical changes to how we, as a society, think about health. But they can be implemented today.

We have only been mucking about in the genome for a few years. We have already made mistakes. We will surely make more. Let's avoid making another.

I completely agree with yours and Lisa Parker’s takes that Steven’s proposal is another example of retroactive American healthcare, and that such strategies cause more suffering and are ultimately more expensive than proactive approaches. Something that you did not explicitly mention is that the proposal (knocking out of HsMOR in respiratory neurons) would do little to nothing to address addiction, as this receptor would still be present in other parts of the brain. So even if this strategy was feasible, it would not modulate the behavior, and certainly not the conditions, that make people susceptible to opioid dependence. Beyond the issue of off-target effects, it seems highly unlikely that the delivery strategy would be effective enough to reach all, or even most, respiratory neurons. Additionally, I would imagine that the cost of this strategy would be enormous, and certainly more expensive than preventative measures like adequate mental health care and jobs programs that would address causes of the opioid crisis, not just a symptom, as Steven’s proposal does.