Via Wikimedia

Produced in partnership with NPR Scicommers

The neurons that make fruit flies interested in sex are turned on by song

Fruit flies go so far as to have species specific melodies and chords

For years scientists were puzzled by how the song of one lover influences another. Now, scientists at Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Janelia Research Campus have helped piece it together. The researchers discovered a neuronal circuit in the female fly that influences her receptivity to a potential mate’s song.

Fruit fly courtship begins with the male’s song. To entice his partner, the male fly sings by extending a wing and vibrating it to produce an acoustic signal. If the male successfully woos the female, she will open her vaginal plates to mate.

“The male has to develop the correct song, meanwhile the female must recognize it,” said Kaiyu Wang, co-lead author of the Nature paper describing the work Like all good social communication, it takes two.

Previously, the researchers uncovered neural networks in the male that compel him to sing, but how the melody influences female receptivity was unknown.

Head of the lab Dr. Barry Dickson, had a hunch. He understood that in the fly brain there are circuits unique to each sex “that make the male and female behave differently.” To identify the neurons responsible for vaginal plate opening, the researchers studied female-specific neurons.

This was no easy task. According to neurogenetics expert Dr. Douglas Portman, “this work could not have been done without the huge amount of work behind the scenes,” referring to a collection of genetic tools developed by the authors. The tools are analogous to a molecular switchboard; researchers can use them to switch “on” or “off” neurons of interest. Portman is an Associate Professor of Biomedical Genetics and Neuroscience at the University of Rochester unaffiliated with the study.

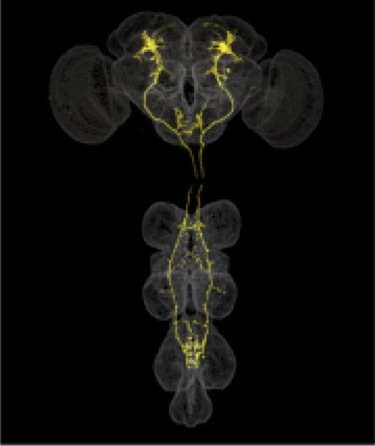

The class of neurons called the vpoDN (in yellow) inside the female fly brain integrate the male serenade in her decision to mate

Dickson lab

Two additional resources were crucial to the work: optogenetic tools and the Connectome. Optogenetic tools use laser lights to control brain cell, or neuronal, activity in living flies. The Connectome, once complete, will be a full map of all the neurons in the fly brain and how they are connected. Portman emphasized that Dickson’s use of the partial Connectome was a trailblazing endeavor; the resource has been around since 2017, but has only been used a handful of times to define the relationship between neuron activity and behavior.

With lasers and brain-map in hand, the authors peered into the female fruit fly brain during various experimental conditions to uncover which neurons were important for vaginal plate opening and mating.

In certain conditions, the male sang and sang, but to no avail. Such conditions informed the researchers that a class of female-specific descending neurons, called the vpoDN, integrate the male serenade as sensory information to open the vaginal plates.

When the vpoDN were experimentally turned off with optogenetic technology, so were the females, despite even the best serenade. Similarly, when the researchers clipped off the male’s wings to eliminate the love song, or deafened the female, she was disinterested. However, even in the mute male and deaf female, the researchers were able to activate the female vpoDN using optogenetic technology.

“When you activated the vpoDN, you would get vaginal plate opening. Conversely, when you silence them, females are unreceptive,” said Dickson. “Identifying that these neurons were responsible was a huge result.”

Dickson explained it is essential that the female hear the right male, meaning one of her species. The team showed that females are attuned to a species-specific chord in the song. However, if the recorded song of a different fly species was edited to include the species-specific melody, even virgin females would open their vaginal plates. Dickson believes this to be “the most beautiful result in the whole paper” because it demonstrates how crucial it is for the female to hear the song of her species.

“This song really matters; that’s how they make the choice,” he said.

But it wasn’t all about the male’s song. The team realized that physiological cues from the female’s body needed to integrate with extrinsic cues of the love song. The receptivity of the female is also influenced by whether or not she has previously mated. According to Dickson, a second class of neurons deactivate after a female mates, eliminating the signal to open the vaginal plates.

Dickson and his team illuminated part of the neural circuitry behind the fruit fly serenade, an essential mating behavior. For the female fruit fly, the decision to accept a mate requires the right musical performance in the context of previous mating behavior.

Animals can display a diverse assortment of behaviors to woo potential mates. Dickson’s discovery at the level of individual neurons and their connections provides a paradigm for thinking about how brains work to influence behavior. By mapping the vpoDN connections, Dickson’s team exemplified how a brain can funnel multiple kinds of inputs, compare them, and ultimately make a decision.

It's not just the song and it’s not just the singer; it’s the audience that determines an effective serenade.