Could we develop plants to absorb our excess carbon?

Salk plant biologists have a bold solution to climate change

What if plants could help us fight climate change?

It might seem like wishful thinking, or just plain anthropomorphic, but plants are our natural allies in this existential struggle.

Plants — historically speaking, our most reliable friends — have evolved to capture and store atmospheric carbon dioxide. They use energy from the sun to convert CO2 and water into sugar and other important molecules, generating oxygen as a byproduct that sustains life on our planet.

The problem is, we have continuously cut down forests and increased CO2 emissions over the millennia, leading to a planet-warming build-up of CO2 in the atmosphere. Unfortunately, planting more trees is not enough to absorb the excess carbon dioxide that humans have created.

A team of scientists at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California, think plants might be able to help in another way.

These scientists are trying to optimize plants’ natural ability to capture and store carbon, as part of Salk’s Harnessing Plants Initiative (HPI). The approach, co-led by Salk Professors Joanne Chory and Wolfgang Busch — along with Professor Joseph Ecker, Associate Professor Julie Law, Professor Joseph Noel, and Research Professor Todd Michael — will help plants draw down and store more carbon than ever before, mitigating some of the effects of climate change, while providing more food, fuel and fiber for a growing population.

“Plants can help us make a dent in climate change,” said Chory in a recent podcast. “We want to harness this natural process to increase carbon stores in order to reduce atmospheric CO2.”

The Root of the Solution

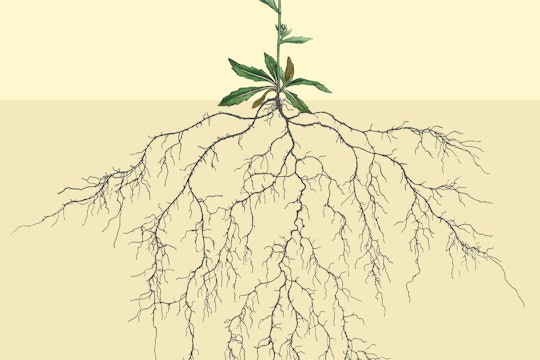

Busch studies plants’ roots. These roots draw water and nutrients from the soil, and store carbon in the form of a long-lasting molecule called suberin, also known as cork. Suberin naturally absorbs carbon, yet resists decomposition, while helping the plant withstand stress, such as drought.

Busch seeks to understand what genes and molecular mechanisms shape plant root growth, in order to help plants grow bigger, more robust root systems that absorb larger amounts of carbon, burying it in the ground in the form of suberin and other polymers.

“We need to use plant genetics to make plants better at storing carbon dioxide,” Busch says in the latest episode of Where Cures Begin. “They are such a powerful agent in the carbon cycle. If we optimize them a little bit more, it will have a huge impact on the carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere.”

Salk's plant biology team, from left: Joseph Noel, Joseph Ecker, Julie Law, Joanne Chory, Wolfgang Busch. (Not pictured: Todd Michael.)

His team has already made significant progress in this pursuit. Last year, they discovered a gene that determines whether a root grows deep or shallow in the soil, along with a gene responsible for helping plants thrive in stressful environments. Once the scientists uncover how these plants are naturally increasing their suberin levels, they will transfer the genetic traits to six prevalent crops, including corn, soybean, rice, wheat, cotton and canola.

The enhanced root systems will also protect the plants from stressors caused by climate change. The additional carbon in the soil will make the soil richer, promoting better crop yields and more food for a growing global population. In addition, the scientists are also exploring ways to take advantage of plant ecosystems in the earth’s oceans, rivers and wetlands that store far more carbon than their land-based relatives.

To learn more about the Harnessing Plants Initiative to mitigate the effects of climate change, visit salk.edu/HPI and tune in to the Salk Institute’s podcast, Where Cures Begin, with Joanne Chory (Season 1) and Wolfgang Busch (Season 2).