A version of this story originally appeared on OceanBites

Seagrass meadows protect fish, coral and humans from disease – and we’re losing them

This seemingly mundane plant might be more important than we realize.

If you’ve seen seagrass meadows on the ocean floor while snorkeling and not given them a second thought, you’re not alone. Seagrass may seem mundane, but the plants have a huge impact on the livelihood and well being millions of people around the world.

Lush underwater seagrass meadows help protect ecosystems we rely on for food, against erosion and extreme weather – reason enough to be alarmed that we are losing them at relatively high rates. We’re now learning that they’re important for another reason too: like their land-based counterparts, seagrass may help reduce the risk of disease outbreaks in fish, invertebrates, coral reefs and even humans.

We’ve long known that terrestrial plants combat bacteria and other pathogens by producing natural pesticides, competing for nutrients, and altering the chemistry of the soil and water. The marine plants that make up the most common coastal ecosystem on earth appear to have similar capabilities. Previous lab studies have even shown that extracted chemicals from seagrasses kill pathogens. Now, for the first time, scientists have found evidence that seagrasses do this in the wild as well.

Birds-eye-view of site locations in Sulawesi, Indonesia

To study the pathogen-killing ability of seagrasses, an international team of scientists lead by Joleah Lamb of Cornell University collected water samples from multiple sites at different depths from four islands along the western coast of Sulawesi, Indonesia. They chose these locations because the islands shared important characteristics: sediment type, human population density, the absence of basic sewage treatment, and thin soils that do not hold wastewater and are susceptible to pollution. While sampling sites in different locations can never be identical to each other, choosing sites with similar characteristics controls as many variables as possible and allows analysis to focus on the relationship between the presence of seagrasses and pathogen levels in the water.

Benchmark Bacteria

In order to assess how seagrasses might affect human health, the researchers tested 400 water samples for Enterococcus, a lactic acid bacteria that can cause urinary tract infections, meningitis, and other health problems. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency uses the bacteria as an indicator of human health because it’s often found alongside other disease-causing pathogens in wastewater pollution.

The team analyzed water samples for Enterococcus levels, and found that samples from locations closest to the shore contained 10 times the EPA’s recommended levels for recreational water. In other words, you wouldn’t want to swim there. However, samples taken from sites with seagrasses nearby had 3 times lower pathogen levels compared to sites without seagrasses nearby. Their findings weren’t limited to Enterococcus. The team also found lower levels of pathogens that cause everything from disease in fish to food poisoning in humans in locations with seagrass nearby.

Coral Care

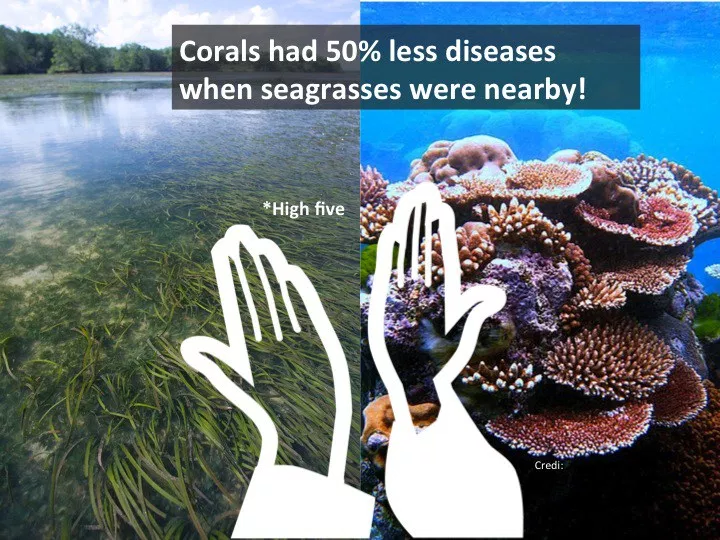

The researchers also visually examined more than 8,000 corals for signs of damage associated with coral bleaching, coral disease, and physical damage from moving debris. Unsurprisingly, they found that corals at sites with seagrasses nearby had half the amount of diseases than corals without seagrasses nearby.

Ria Tan via flickr, CC-BY-NC-ND. Coral reef photo credit – Tony Hudson via Wikipedia Commons CC BY-SA. High five – Larske via Wikipedia Commons CC BY-SA

Coral reefs, one of the most important ocean ecosystems on earth, face increasing threats from climate change, ocean acidification, and development. That makes understanding seagrass, which contribute to their health, even more important. Unfortunately, seagrasses are facing their own set of threats. Even though they’re a fairly common ocean ecosystem, nearly 20% of seagrass species we’ve studied are endangered, mostly due to the compounding effects of destructive human activity like dredging, agricultural and construction runoff and even boat anchors and propellers.

The good news is that there are ways to prevent seagrass decline. Creating international legislation to protect seagrass meadows would be a strong start. These agreements should call for people working near seagrass meadows to create strong management plants that prevent or minimize excess fertilizer runoff and construction dumping, prohibit boat anchoring and dredging, and manage fisheries so top predators aren’t eliminated from ecosystems. We can also restore seagrass by planting or seeding, which is how communities in Florida and the Chesapeake Bay were able to successfully restore seagrass.

We all stand to lose from seagrass depletion. 275 million people live in coastal communities that depend on coral reefs for their lives and livelihoods. Even if you don’t live near the ocean, you probably interact with it. Not getting a disease or infection when you eat seafood or go swimming at the beach? That’s worth paying attention to seagrass, even if it’s unremarkable at first glance.

Featured Article

- Lamb, JB, van de Water, JAJM, Bourne, DG, Altier, C, Hein, MY, Fiorenza, EA, Abu, N, Jompa, J, Harvell, CD (2017). Seagrass ecosystems reduce exposure to bacterial pathogens of humans, fishes and invertebrates. Science 355(6326): 731-733. doi: 10.1126/science.aal1956