National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH

19 answers referencing 32 sources

Your coronavirus questions, answered by experts

- How long could I have the virus before showing symptoms?

- How does the virus spread between people?

- How can we estimate how far coronavirus will spread?

- How does a virus that apparently started in Wuhan, China spread around the world?

- Do we know why COVID-19 is spreading so much farther compared to related viruses like SARS and MERS?

- What is the difference between coronavirus, COVID-19, and SARS-CoV-2?

- Some "social distancing" explainers — including Massive's — say "stay home." Others say that going outdoors is okay, or even beneficial, as long as people stay >10ft apart. Which is it?

- What percent of the population needs to be infected with coronavirus and recover before herd immunity kicks in?

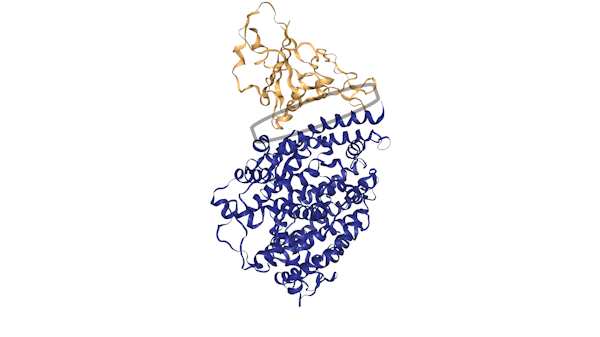

- How does SARS-CoV-2 get into our cells and can we prevent it from doing so?

- Why are so few people infected in Russia when tens of thousands are sick in China and Europe?

- It seems like cats are also susceptible to COVID-19 but dogs aren't, is there any explanation for that?

- Will UV light, like from the sun, kill coronavirus?

- I've heard people talk about using antibiotics to treat coronavirus. Can you explain why antibiotics don’t work to treat viruses directly?

- Do we know why children are less likely to show severe symptoms?

- How can I infect others if I don't feel sick?

- If one has a normal temperature does that rule out having COVID-19?

- Can a COVID-19 swab test pierce your brain?

- What COVID-19 treatment did President Trump receive? Did it contain human embryonic stem cells?

- Why do the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines need to be kept so cold?

Do you have a different question? Send it to our community of experts:

Submit your questionAre you an expert in this area? Help answer our readers’ questions:

Join our communityThe incubation period of COVID-19 virus, combined with the possibility that people can possibly spread the disease without showing symptoms, partially explains how the disease spread so widely before being detected.

This incubation period between infection and symptoms allows pathogens to move stealthily across borders before being detected. It is likely that travelers passing through Wuhan were unknowingly encountering people who were infected with SARS-COV-2, the virus that causes the disease known as COVID-19. These travelers may have returned home without knowing they were infected.

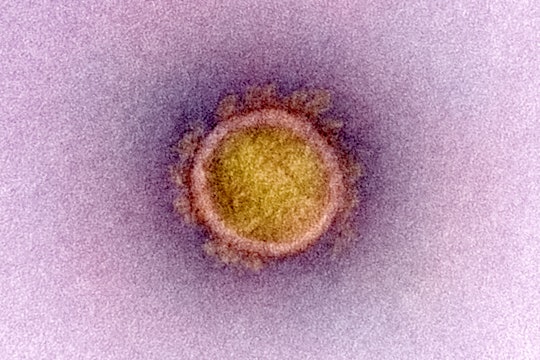

Other specific features of SARS-CoV-2 can also help explain how it is making its way around the world, particularly how it moves between people and its infectiousness. We know that SARS-CoV-2 is spread through person-to-person contact and by touching surfaces or objects that has the virus on them.

The World Health Organization has officially declared this outbreak a pandemic and the public health community is continuing to work diligently to further our understanding of this novel disease and to prevent it from spreading. As such, we now must use one of our more stringent methods to slow the spread of this infectious disease and this includes limiting all unnecessary movement and gatherings, including working from home if possible, limiting unnecessary travel, and avoiding large crowds like those at concerts or sporting events.

It is time to approach our daily lives differently. While everyone can’t enact all social distancing measures, individual actions make a big difference. As always: please continue to wash your hands, refrain from touching your face, and stay home if possible. Being prepared is a great way to reduce anxiety and panic.

Do we know why COVID-19 is spreading so much farther compared to related viruses like SARS and MERS?

TL;DR

Most secondary infections from SARS and MERS occurred in hospitals, which prevented community spread of the virus. With COVID-19, we may be seeing more secondary infections and subsequent community spread as a result of primary cases not being tested, either due to lack of tests or lack of severe symptoms.

This is still under investigation, with new data available every day. Beyond features of virus spread, sometimes it is helpful to look at other aspects of a virus to better understand how it behaves.

The case fatality rate (CFR), which is the number of deaths from a given disease divided by the total number of people with confirmed illness, can be used as a measure of disease severity. The global fatality rate for COVID-19 was initially reported as at about 2.3 percent, though WHO reporting has increased this rate to 3.4 percent.

SARS and MERS have higher case fatality rates than COVID-19. The 2003 outbreak of SARS had a case fatality rate of around 10% (774 deaths out of 8098 cases), while MERS has killed 34% of people with the illness between 2012 and 2019 (858 deaths from 2494 cases). However, COVID-19 has lead to more total deaths because more people have been infected.

One hypothesis for the higher case fatality rates with SARS and MERS compared to COVID-19 is related to secondary infections (infections that occur during or after the initial infection). Most secondary infections from SARS and MERS occurred in hospitals, which prevented community spread of the virus. With COVID-19, we may be seeing more secondary infections and subsequent community spread as a result of primary cases not being tested, either due to lack of tests or lack of severe symptoms.

This community spread will continue as we are still having difficulties in identifying and counting mild cases of COVID-19. It currently seems COVID-19 is just as transmissible as SARS and MERS but not as deadly. However, everything we know about the virus, including R0 and case fatality rates, is preliminary and will evolve as the pandemic does.

SARS-CoV-2 is the virus responsible for the novel coronavirus disease. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) chosen name, COVID-19, is just short for "coronavirus disease" and their preferred nomenclature for the virus is "the virus responsible for COVID-19" or "the COVID-19 virus." For readability's sake, Massive often refers to the virus simply as "coronavirus."

No, a swab can't poke a hole in your brain. even if it feels like the swab is all the way into your head. News stories about piercing the brain during a COVID test are generally due to a rare weak spot or defect at the base of a skull. According to nose surgeon Carl Philpott, "It is extremely unlikely for any person who doesn’t have this pre-existing weakness in the nose to cause any damage with a swab."

When President Donald Trump was sick with COVID-19, he immediately received an experimental polyclonal antibody cocktail made by Regeneron, a large biopharma company. As of October 2020, this treatment had not yet been evaluated by the FDA.

Despite rumors circulating online, the antibodies were developed using "humanized" mouse embryonic stem cells. The treatment does not contain human cells.

Read more about the experimental treatment in our full story.

Pfizer-BioNTech’s vaccine requires -70°C (-94°F), colder than the South Pole, and only lasts around 5 days once placed in a refrigerator. Moderna’s vaccine is a bit more forgiving, shipped at -20°C (-4°F) and good for a month in a refrigerator. For comparison, inactivated or live attenuated vaccines (like the flu vaccine) are stored at typical refrigerator temperatures, about 2-8°C (46°F).

Both of these vaccines are RNA-based. Instead of priming the immune system with a dead virus or a piece of a virus, as vaccines in the past have done, these vaccines deliver a template – RNA – for our cells to make a single protein from SARS-CoV-2. The body creates the protein, generates a protective immune response, then throws away the RNA – much like kids passing notes in class, then crumpling them up and tossing them in the trash.

RNA is notorious for its instability. Before working with RNA, it’s common for scientists working with it in a lab to clean their workspace of “RNases” or ubiquitous environmental enzymes that break down RNA quickly. Unlike DNA, which typically consists of two strands and contains a submolecule called deoxyribose (hence “DNA”), RNA is single-stranded and contains ribose (hence “RNA”), which makes RNA molecules more susceptible to degradation. Despite the chemical modifications and packaging these companies use to make it more resistant, it still suffers compared to DNA or protein.

The extreme temperatures slow down chemical and enzymatic degradation, allowing the RNA vaccines to maintain their efficacy from manufacturing to injection. RNA’s instability is good for our cells: many copies of RNA are transcribed from DNA templates, which are then used to create proteins. But as the proteins required by the cell are made, the instructions are degraded away.

Read more about the cold requirements and the cold supply chain in this story.