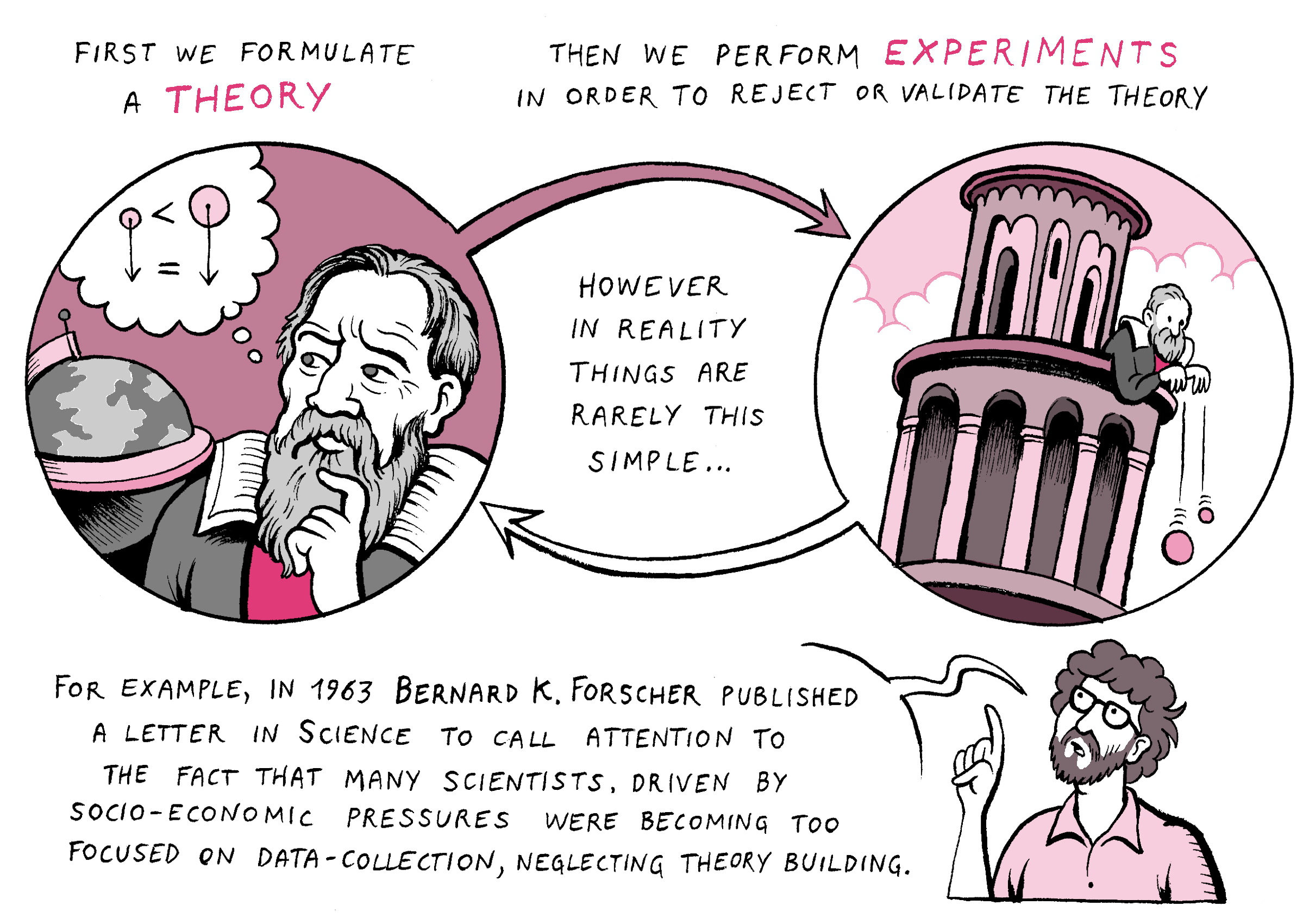

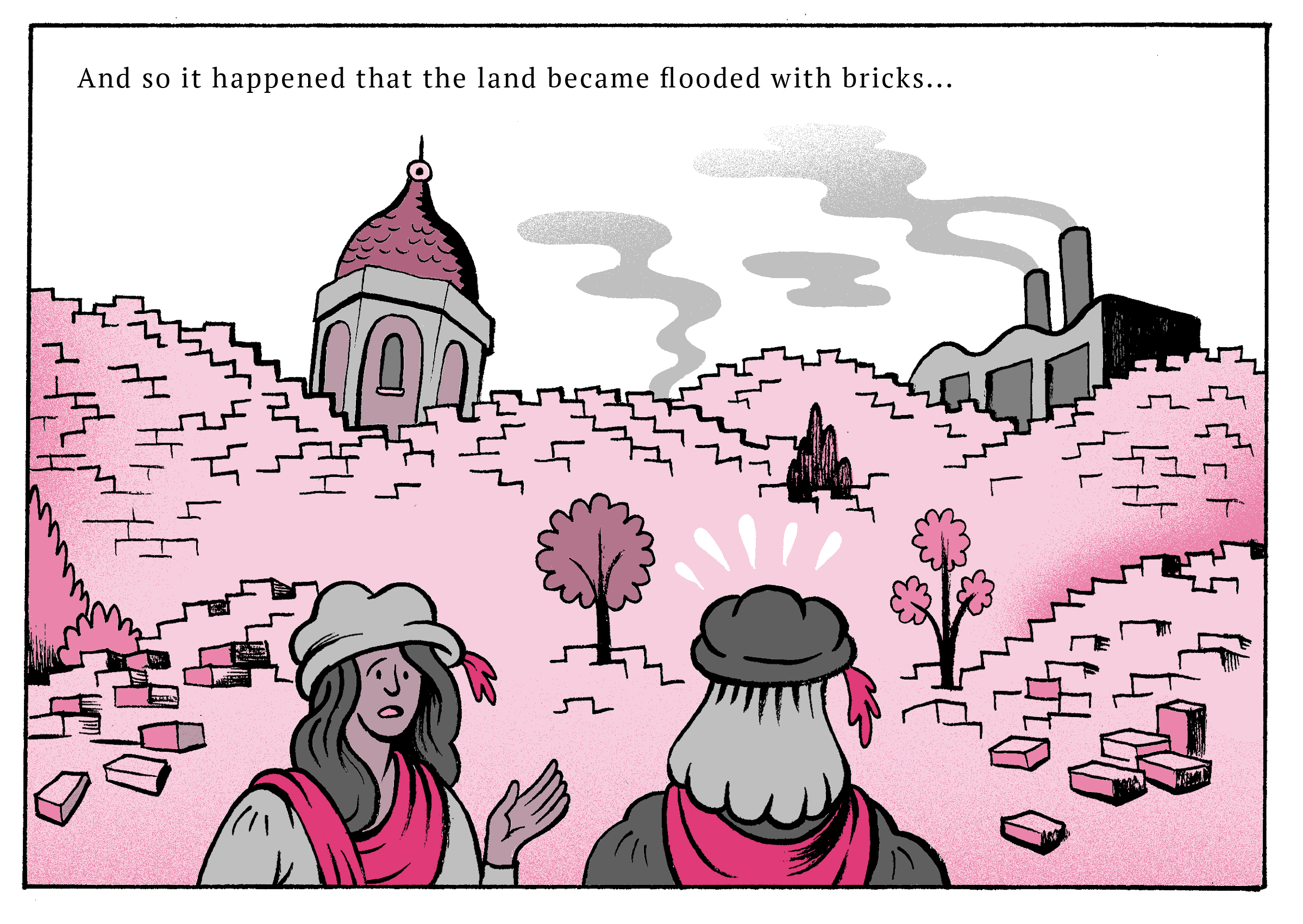

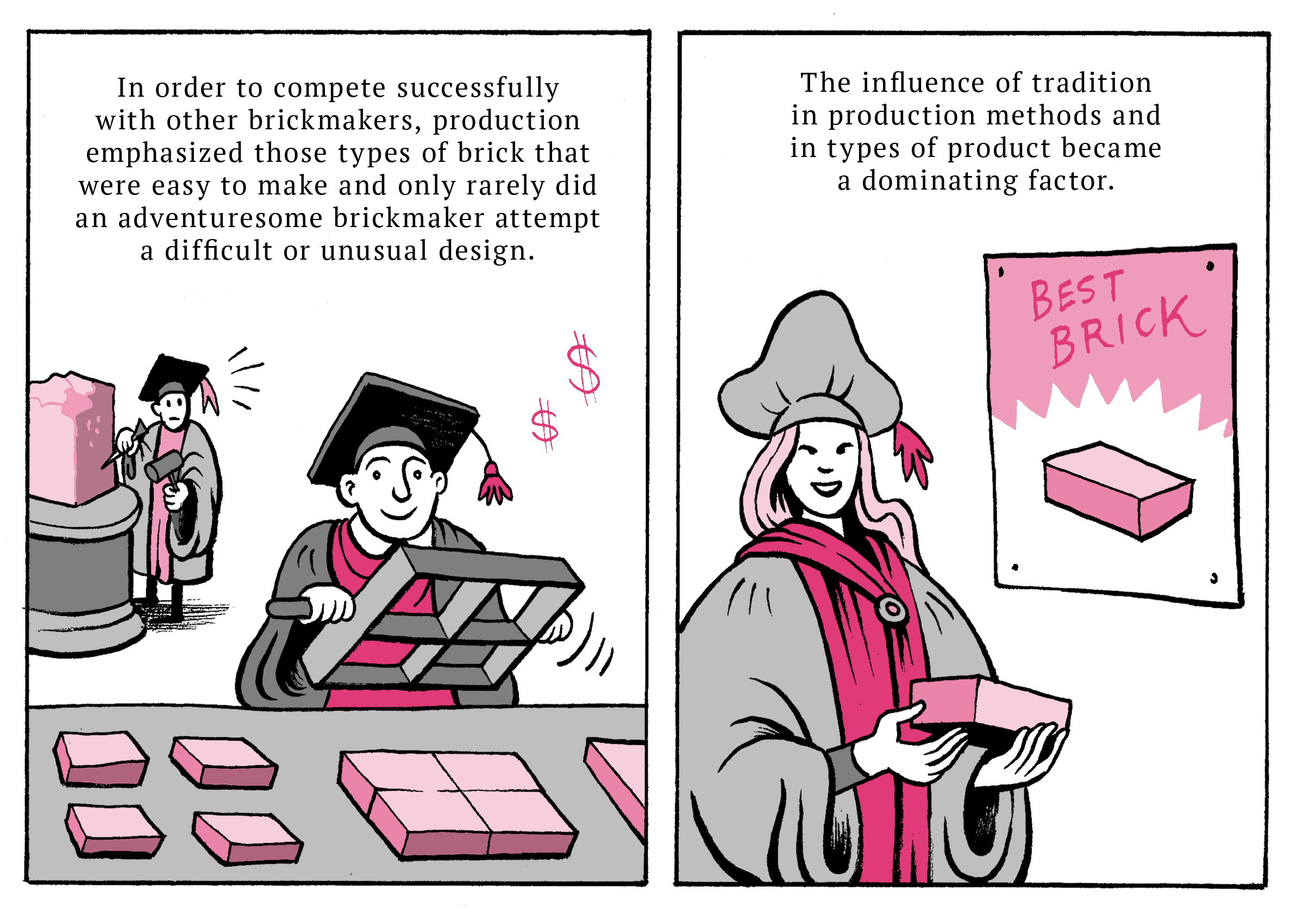

Scientific knowledge is drowning in a flood of research

A comic about the problems with the -omics, illustrated by Matteo Farinella

Neuroscience

Columbia University

Reprinted with permission of the family of Bernard K. Forscher, with special thanks to Geoffrey P. Forscher.

Peer Commentary

We ask other scientists from our Consortium to respond to articles with commentary from their expert perspective.

Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

Dan Samorodnitsky responds:

Dan Samorodnitsky responds:

What's that joke about computational biology solving the same three problems over and over?

Genomics

University of Alberta

This is such a fantastic illustration of a problem with some modern science. I, however, think the problem’s not as big as it’s made out to be.

I am one of a small set of scientists who think that we don’t yet have enough data/bricks. In my view, we still need data to form predictive models and hypotheses about scientific phenomena, but we need to diversify and connect the various data-types we use to do so. A lot of us are doing this now, using different methods of data production to correct and refine the overall structures of modern scientific thought. Oftentimes more bricks can demolish bad foundations and replace them with something stronger.

Yes, science – especially through new techniques – does sometimes build on older theories with fancier-seeming bricks. But sometimes using fancy bricks reveals facades that would have remained crudely formed, or even incorrectly built.

For example, only through the advances in genomics (and the massive amounts of data produced) were we able to leave behind the terrible gene-centric theory of molecular biology that impeded further discovery for decades.

Senior Editor

I don't think the issue is that there's too much or too little data. There's always been more data than anyone knows what to do with, even before the -omics era. It's like baking bread: you end up with a loaf but your kitchen will be covered with random scraps of dough that end up in the garbage. Every project I've worked on produced interesting data which didn't fit in anywhere and wasn't interesting enough to pursue.

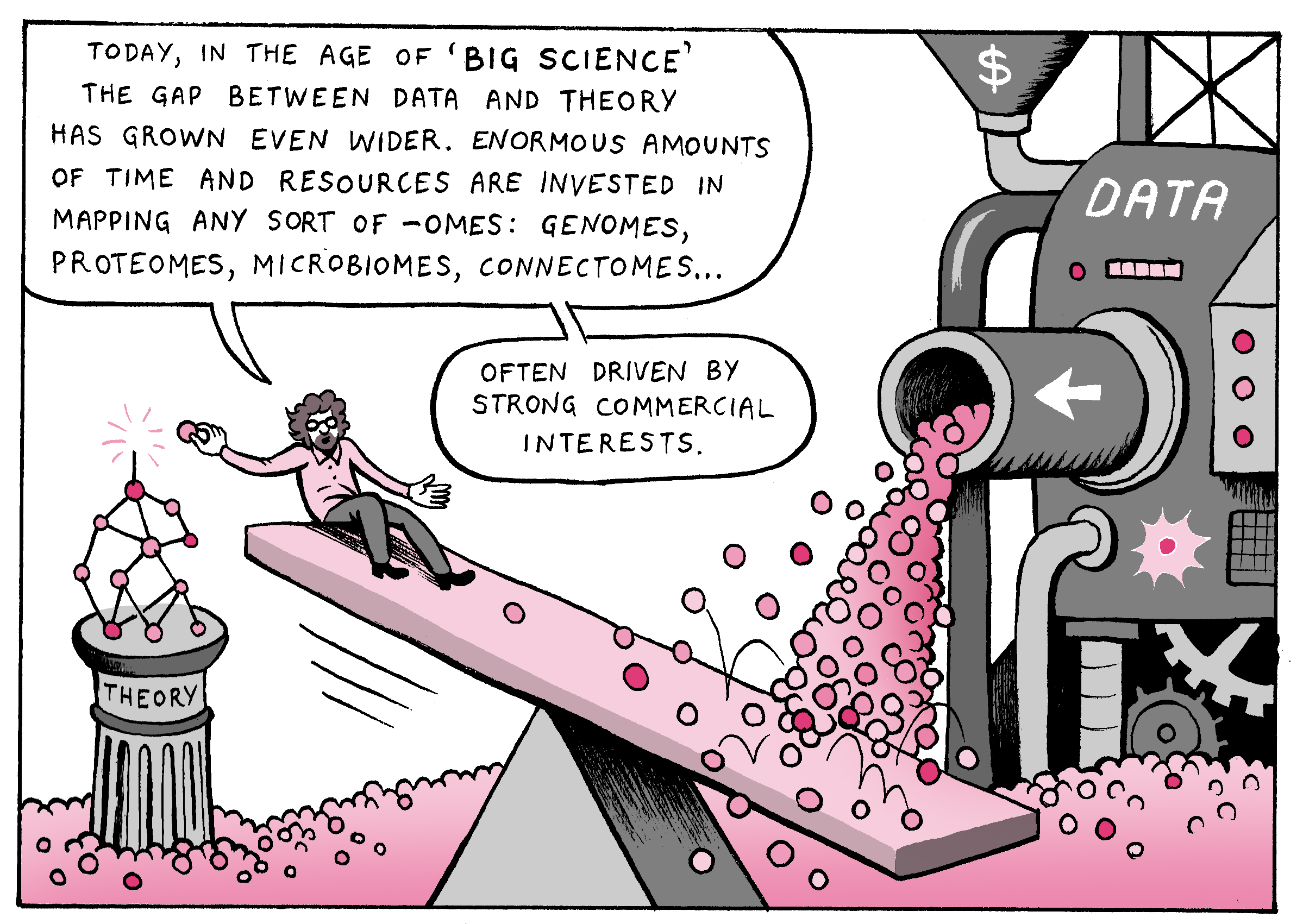

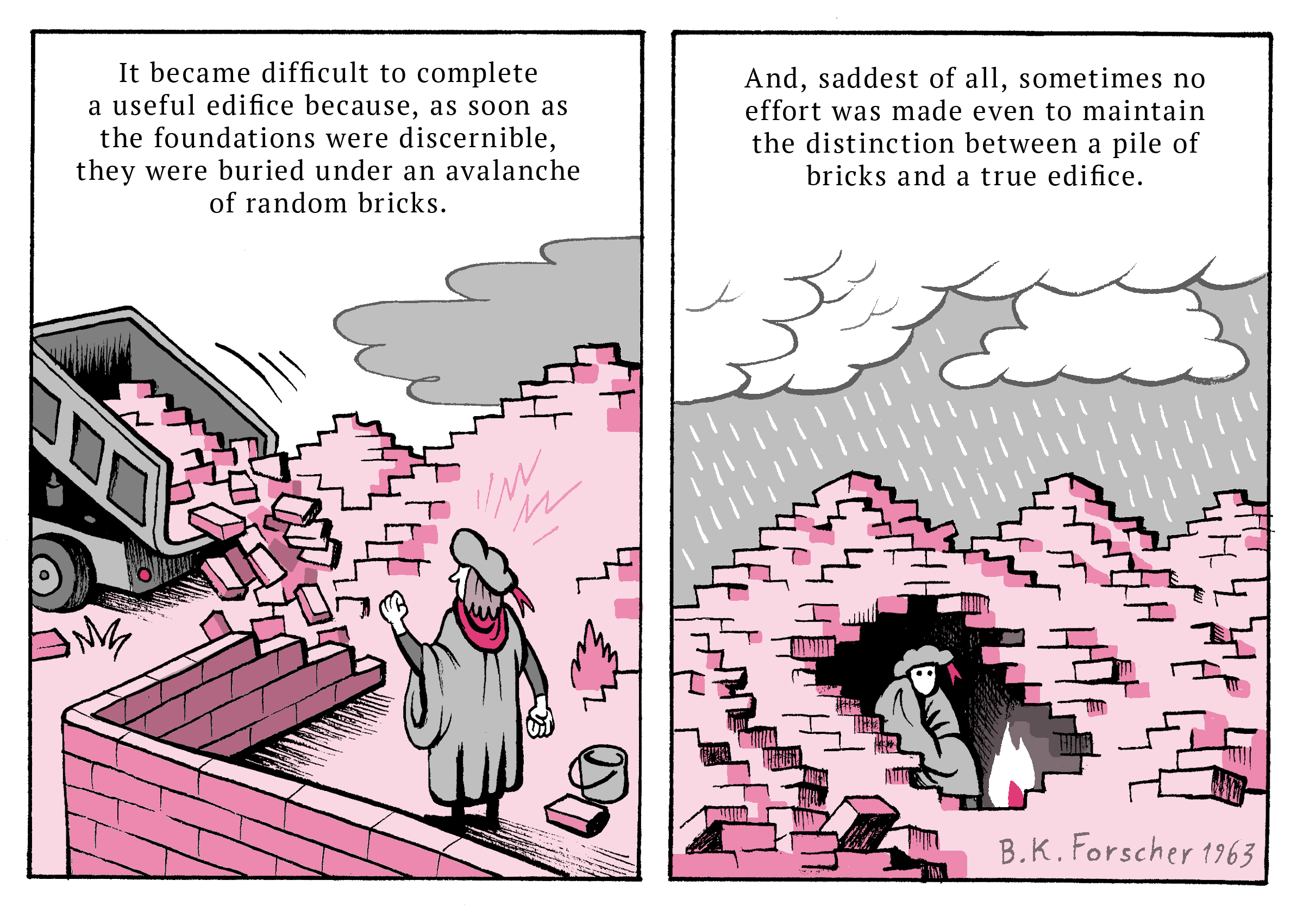

The greater issue that the letter and comic illustrate, in my mind, is that -omics approaches to science prioritize correlating data sets with each other while leaving behind any thought about mechanisms, why things are the way they are.

That, to me, is the edifice. Drawing a map from point A to point B is worthless if you don't pave the road between them. I can't count the number of papers I've read that did mind-bending analysis to show that, say, drinking red wine increases expression of a bunch of genes without stopping to consider why or how or if it even matters. You can base an entire lab on finding new things that haven't been sequenced and sequencing them. That's a viable approach to research today.

David Haggerty responds:

David Haggerty responds:

But even with the -omics breakthroughs, we still don't have the tools to understand what the mechanisms are. Obviously some of the problem is our approach, biases, what is profitable, but we neuroscientists can't figure out how to explain a microchip that runs donkey kong, let alone a neural circuit. It's hard to deem what's important and why, when we still don’t have the full picture in front of us.

Dan Samorodnitsky responds:

Dan Samorodnitsky responds:

All of this makes me feel uneasy, because I've spent my career so far focusing on "small" projects about how proteins function. I literally lie awake at night wondering if I'll be able to get a job in the future with my... old-fashioned skill set.

I don't think -omics approaches are bad or wrong or don't have their place. I just want to live in a world where there's money and appetite for both the forest, which computational approaches look at, and the trees.

David Haggerty responds:

David Haggerty responds:

You’ve hit it on the head.

This touched the job anxiety nerve for me as well, thinking about the droves of specialized PhDs coming out of academia, many of whom are competing for a small set of jobs that don’t actually require that level of specialization.

Neuroscience

Columbia University

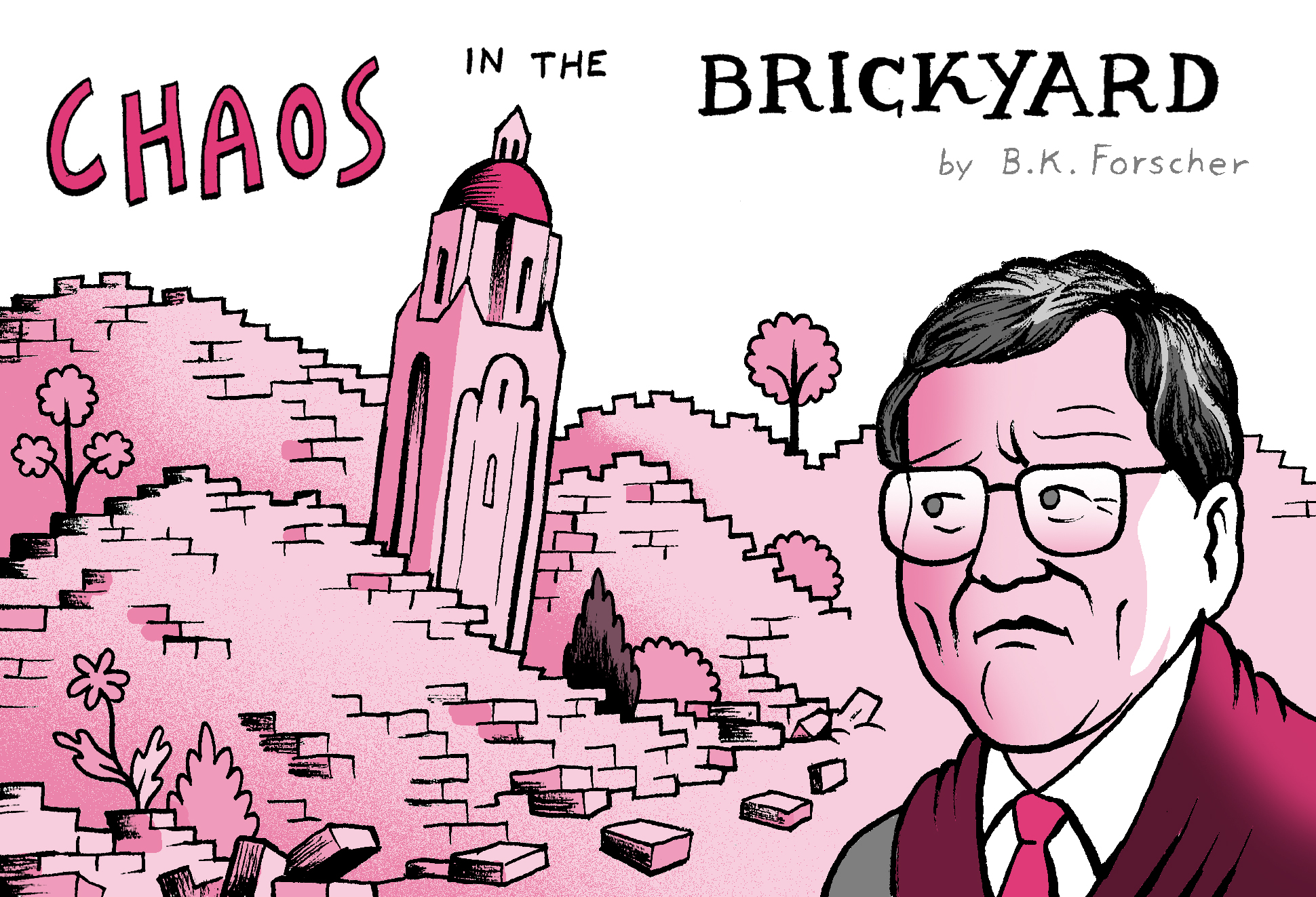

I love the bricks/buildings metaphor because even if it certainly oversimplifies some things (as any metaphor necessarily does) I think it's a great way to visualize scientific practice, especially for our non-scientist friends and policymakers.

Just to reply to a few points in random order:

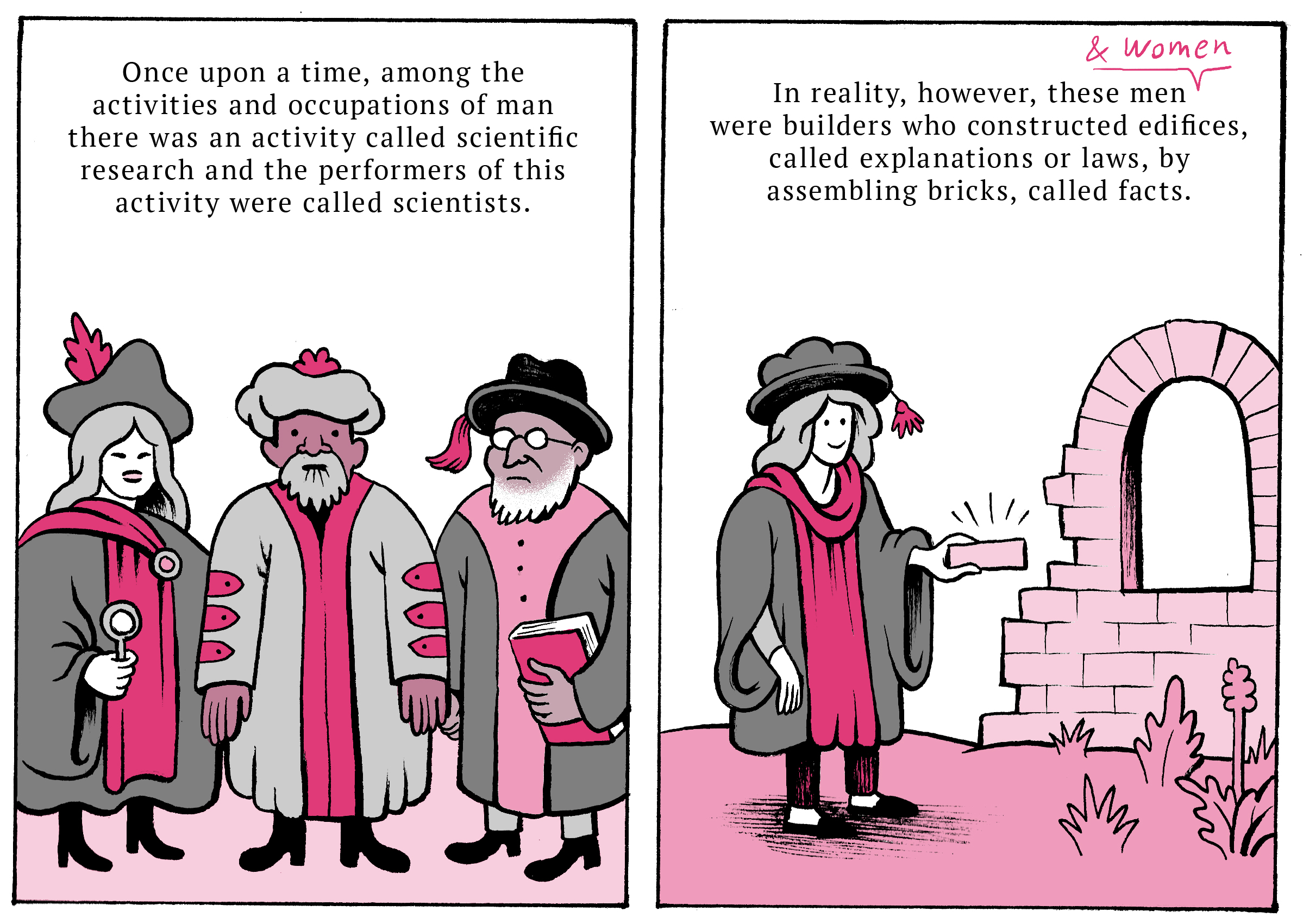

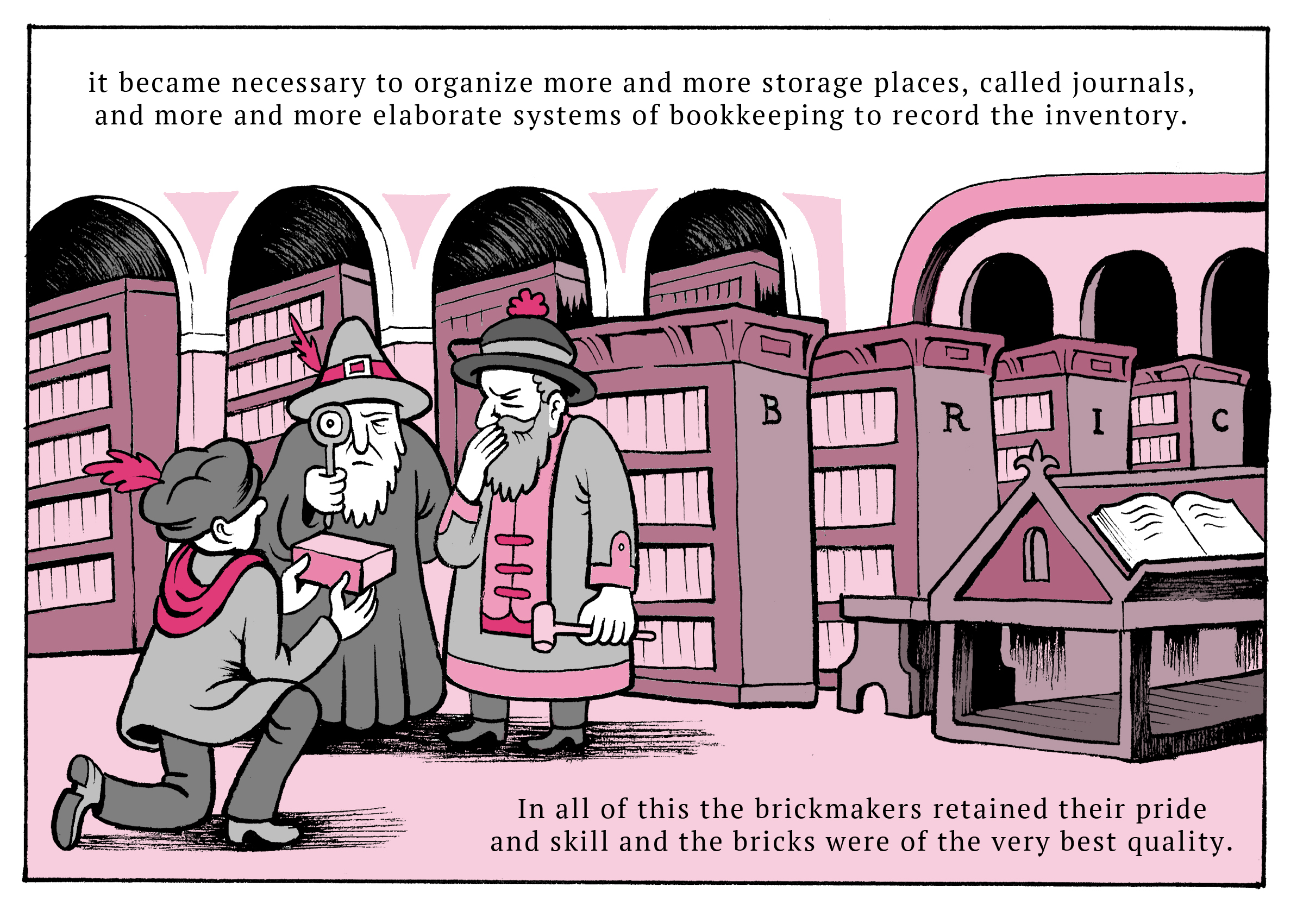

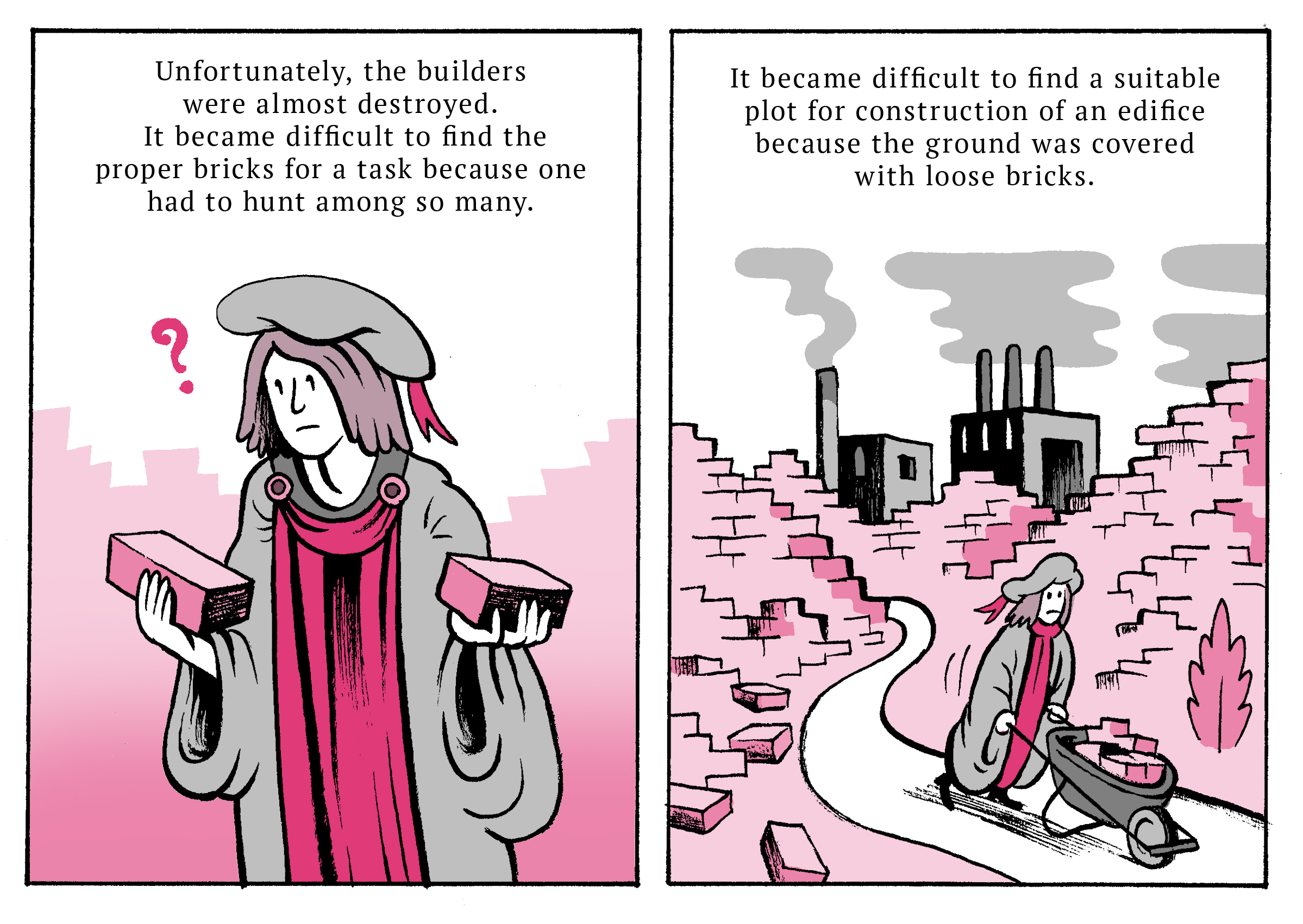

1. I didn't write the letter, so I don't know what Forscher actually meant, but for me the message is not that too much data is 'bad' or theories are somehow more 'noble.' It's just a reminder that to make science we need both: a pile of data without theory doesn't explain anything (it's a description, as Samorodnitsky said) just like a theory unsupported by data is completely useless (just like a beautiful drawing of a building that never gets built).

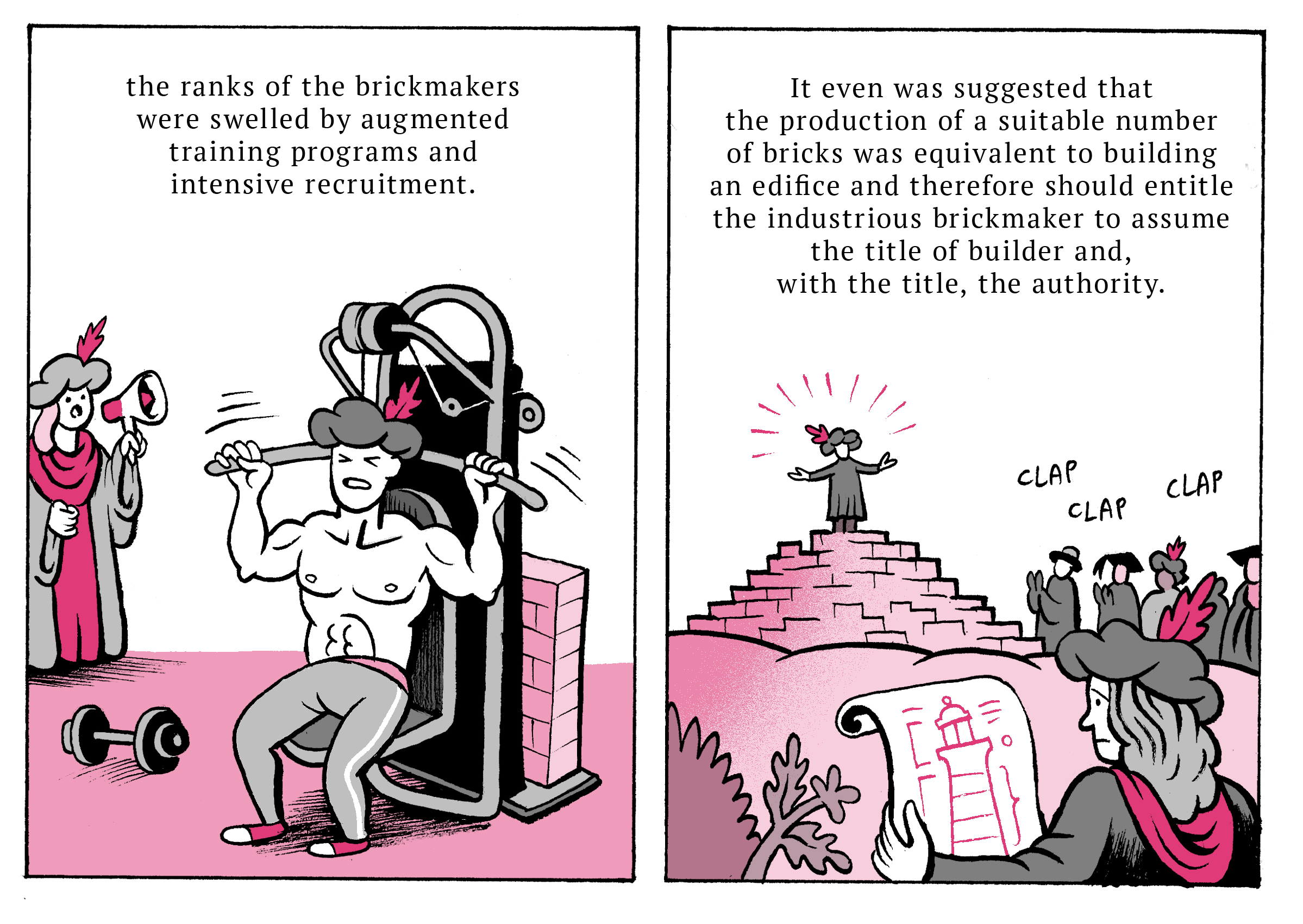

2. By that I don't mean that we all need to do both! And I certainly wouldn't want to suggest that 'brickmakers' are a lower caste, or untrained PhD. Especially in today's age I think it makes perfect sense to have experimental scientists mapping all the -omes they want, and theoretical scientists trying to connect the dots. The problem is that training and funding often favors data over theory (probably because, unlike data, theories are difficult to quantify).

3. Also, Mehta makes a good point: we clearly can't generalize across sciences. Some fields are much more balanced (for example I think physicists are pretty good at giving credit to both theory and experiments). Other are producing mountains of data; others get a bit carried away with their theories (believe me – my PhD was in computational neuroscience!)

Anyway, I hope the job anxiety doesn't get too bad, especially over the holidays! Just keep going, one brick at a time 😀

The letter itself equates brickmakers with junior scientists, compared to the builders, so it seems to me that Forscher was drawing attention to the fact that many students and postdocs are hired to collect data for their PI rather than being encouraged to develop their own theories to test. I guess I would take that further and say they are getting a different (not better or worse) kind of training as someone who achieves their degree by pursuing their own independent projects.

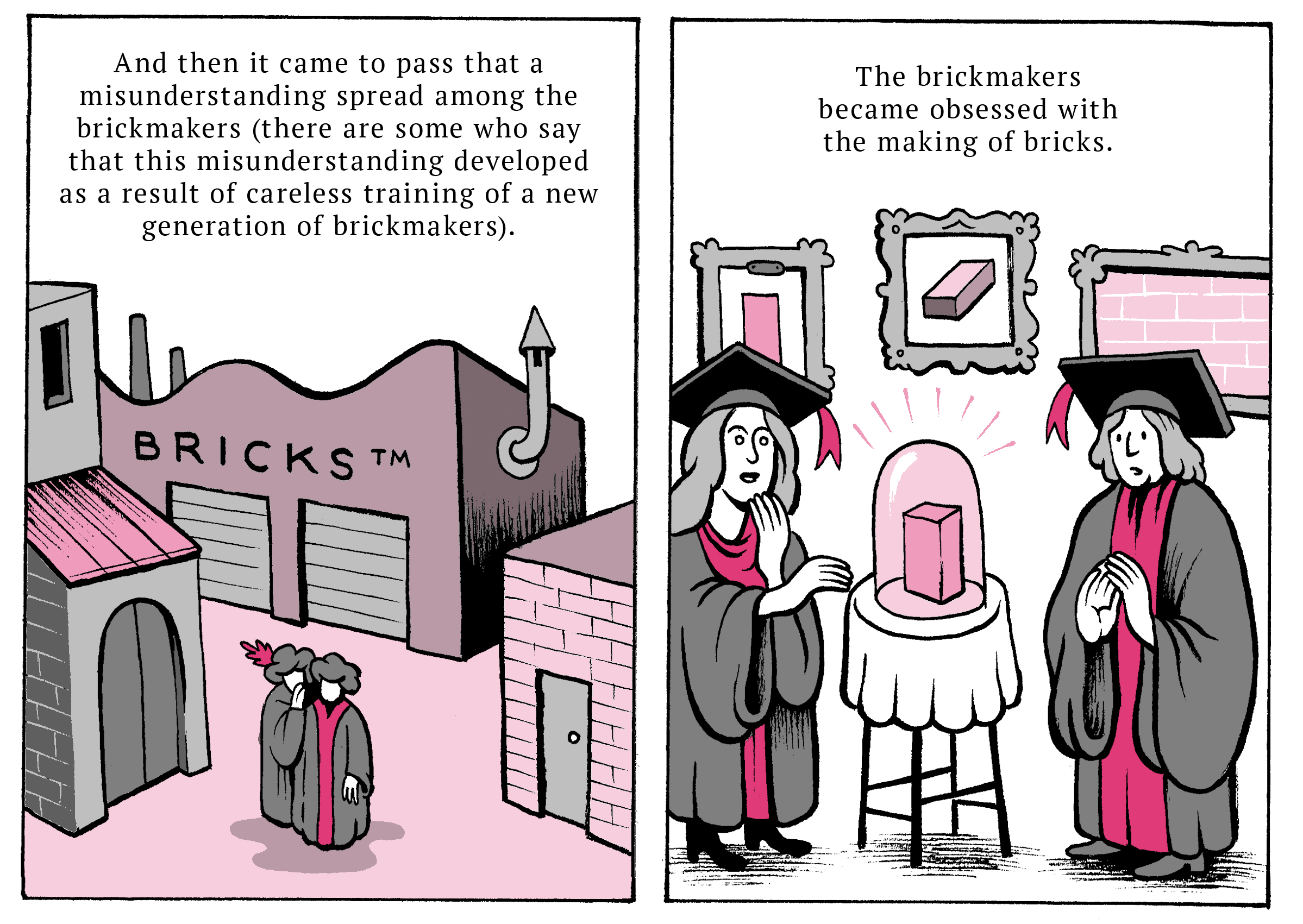

I had not read Bernard K. Forscher’s letter before, and it’s awesome to experience it for the first time through this comic, because it makes the metaphor to academia and the scientific process so incredibly clear. I’m surprised that in 1963 Forscher already saw a trend towards the overproduction of data (bricks) and PhDs (brickmakers).

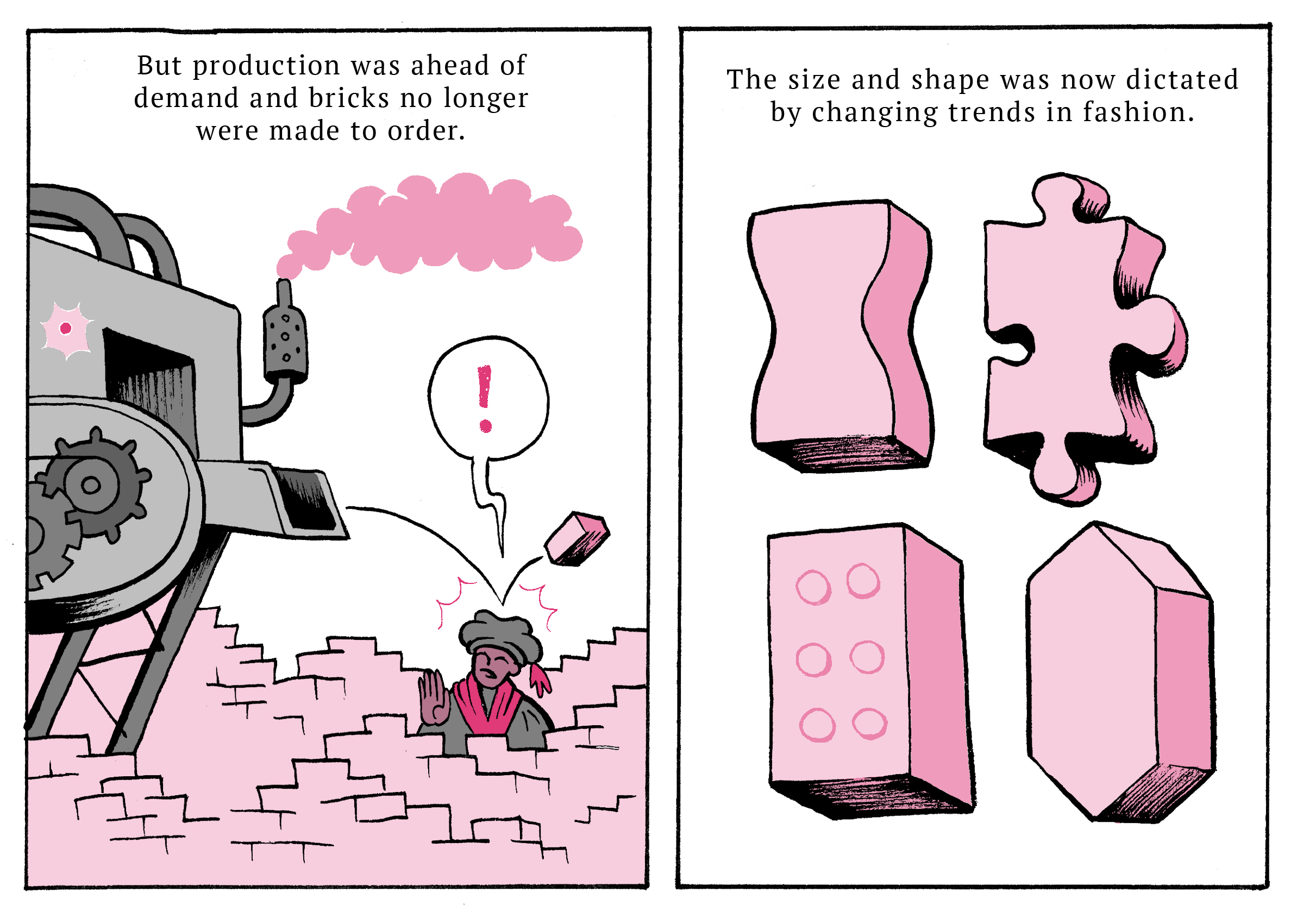

However, I would like to tinker with the metaphor a bit to reflect what I actually see happening. I think there is always a particular edifice in the minds of the brickmakers; scientists are still driven by hypothesis-testing as they collect data. But instead of coming up with new hypotheses, we are using new data to test the same ones over and over again.

We brickmakers aren’t given enough time to come up with new building plans, so we focus on those that are well established.

My field was initially very theoretical, and now has been flooded with studies that use genomics to re-test the same theories using different techniques and organisms. It’s not that we’ve created a pile of bricks and no edifice, it’s that scientists are building over the old bricks with fancier bricks on the same edifice.