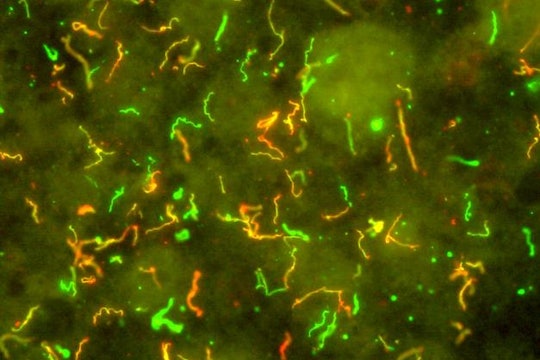

NIAID / Flickr

The Lyme wars are upon us. We should probably read up on them

By 2050, 12 percent of the US population will likely be infected by Lyme-causing pathogen

After reading Mary Beth Pfeiffer's engrossing new book, Lyme, you will probably want to kill any tick you can find, donate to Lyme research, and find out if you are at risk for tick-borne diseases.

Spoiler alert: your risk is likely increasing. Ticks, some of whom carry the pathogenic bacteria that causes Lyme, can now survive in environments where they would have frozen to death 30 years ago. The good news is that there's a lot of new research coming out about stopping and treating tick-borne illnesses, and a good new book that connects the dots between climate change, ticks, sick people, and policy.

Pfeiffer takes a comprehensive, even-handed look at the "Lyme wars" – on one side, there are doctors who strictly follow the Infectious Disease Society of America guidelines on Lyme, which have been criticized as biased and were subjected to an antitrust investigation. On the other side are the patients and doctors who have experience with chronic or late-stage Lyme disease, which causes joint pain, cognitive impairment, and is sometimes treated with long courses of antibiotics (which the guidelines do not support). Pfeiffer carefully presents both perspectives, while also showcasing individual patients' stories.

A tick carrying Lyme

There's a lot at stake in the Lyme wars for both patients and governments, in part because chronic and acute Lyme are expensive. Treatment is predicted to cost a minimum of $5 billion in 2018 for the US alone. By 2050, 12 percent of the US population will likely be infected by the Borrelia pathogen, and many of those cases will become chronic. As our planet's climate warms and ticks are more able to spread their infections, even more people will be infected around the world. If we don't find effective treatments for Lyme and agree on how to address these illnesses, the problem will become even more unmanageable.

Pfieffer's book is one of few places to get this sort of information on the history of Lyme and how it is connected to changing climate – writing on Lyme is usually directed at people with the disease and focuses on addressing their symptoms. It isn't the first piece published about Lyme and climate change, but it presents an in-depth view of a complex research field.

This book taught me that Lyme is tracked as an indicator of climate change, alongside wildfires and heat-related deaths. Pfieffer makes a compelling argument that Lyme is expanding because of human influences on the environment, from warming temperatures to killing deer.

Island Press

She also addresses the symptoms and challenges that patients face, which is neglected in a lot of scholarly research. My own struggle with chronic pain has made some of the symptoms of late-stage Lyme feel familiar, and as a climate scientist, I thought I knew all the major impacts of future climate change. But even though I had that background knowledge, this book made me really feel the urgency of this issue, instead of just knowing about it on an academic level.

One downside of the book is that some chapters have almost too much evidence, so it starts to feel repetitive. But in a way, that just shows how strong Pfeiffer's arguments are: there is overwhelming evidence that patients with chronic Lyme should be treated, and that we need more research to better understand how tick-borne illnesses will continue to spread in the next century.

Pfeiffer emphasizes the struggles that Lyme patients have, but just begins to touch on their strengths. Patients and doctors are advocating for better understanding by writing about their healthcare experiences or serving in the leadership of nonprofits. Those hard-working patients and doctors show that there is still hope in the fight against Lyme, even as climate change progresses. Pfeiffer's new book can't single-handedly stop the spread of ticks or find a cure for Lyme, but it will spread the word about why this issue is important, urgent, and needs more advocates.