The plant-based food that grows where no other crop can survive

How algae can help us increase the output and coverage of our productive land

By 2050, a mind-boggling 10 billion people will inhabit the Earth. By the time we reach that milestone, many of us will likely be undernourished. Given trends in land use and food production, our ability to feed ourselves in the near future is increasingly at risk, warns a report written by more than 100 experts from 52 countries, published in August by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Luckily, there is a new, promising way of doing just that.

Human activity has already degraded a quarter of the planet’s ice-free surface to the point that it is now agriculturally useless, and these dead zones will continue to grow as the climate changes. To ensure that we can produce enough food to meet the needs of our children and grandchildren’s generations, we need to figure out how to make better use of the limited space we have left. To avoid this future of scarcity, we must increase the productivity of our land.

iWi, a Texas-based nutrition company producing algae based products, thinks marine vegetables could be a significant part of the answer. “Our goal is to create a sustainable food solution for everyone on our planet,” says Miguel Calatayud, chief executive officer of iWi. “We’re doing that by cultivating marine produce outside the ocean, on land that can’t be used for other crops.”

In order to appreciate what a game changer algae could be, it helps to understand how the world’s food production system currently operates. We’ve already claimed much of the planet for ourselves. According to the IPCC report, 70 percent of the earth’s ice-free surface is taken up by agriculture, cities and other forms of human development. This presents a catch-22: in our need to feed our growing population, we contribute to forces that will make that task increasingly difficult. Land use change for agriculture, livestock, and other human activities accounts for 23 percent of total global carbon emissions, according to the IPCC report, and the problem is only growing. Fires, for example, currently rage on either side of the globe—in the Amazon rainforest and in Indonesian Borneo and Sumatra — in places where deforestation has made way for livestock and palm oil plantations, respectively.

iWi

Even as we clear more land for cultivation, we are simultaneously losing land to climate change-driven desertification. According to the IPCC report, half a billion people live in areas of the world that are turning into deserts. Rising temperatures and erratic weather are also wreaking havoc on crop yields, as is soil loss. Crop fields throughout the U.S. Midwest sat barren and water-bogged all summer due to extreme flooding. Arable land—or land with favorable conditions for growing crops—is becoming scarcer even as we need it more than ever.

This is where algae comes in. While it isn’t a blanket solution to the world’s impending land crisis, it does offer a win-win solution for a planet with increasing food production needs but decreasing space to meet those needs. Nannochloropsis, the type of alga that iWi grows, can be raised on non-arable land — including deserts — where no other crops could grow without significant, unsustainable investments. “Arable land is becoming scarce,” says Jakob Nalley, Director of Agronomy at iWi. “But we can potentially grow our algae on arid land, which covers 46 percent of the surface of the planet — limiting the burden of current food production in arable land.”

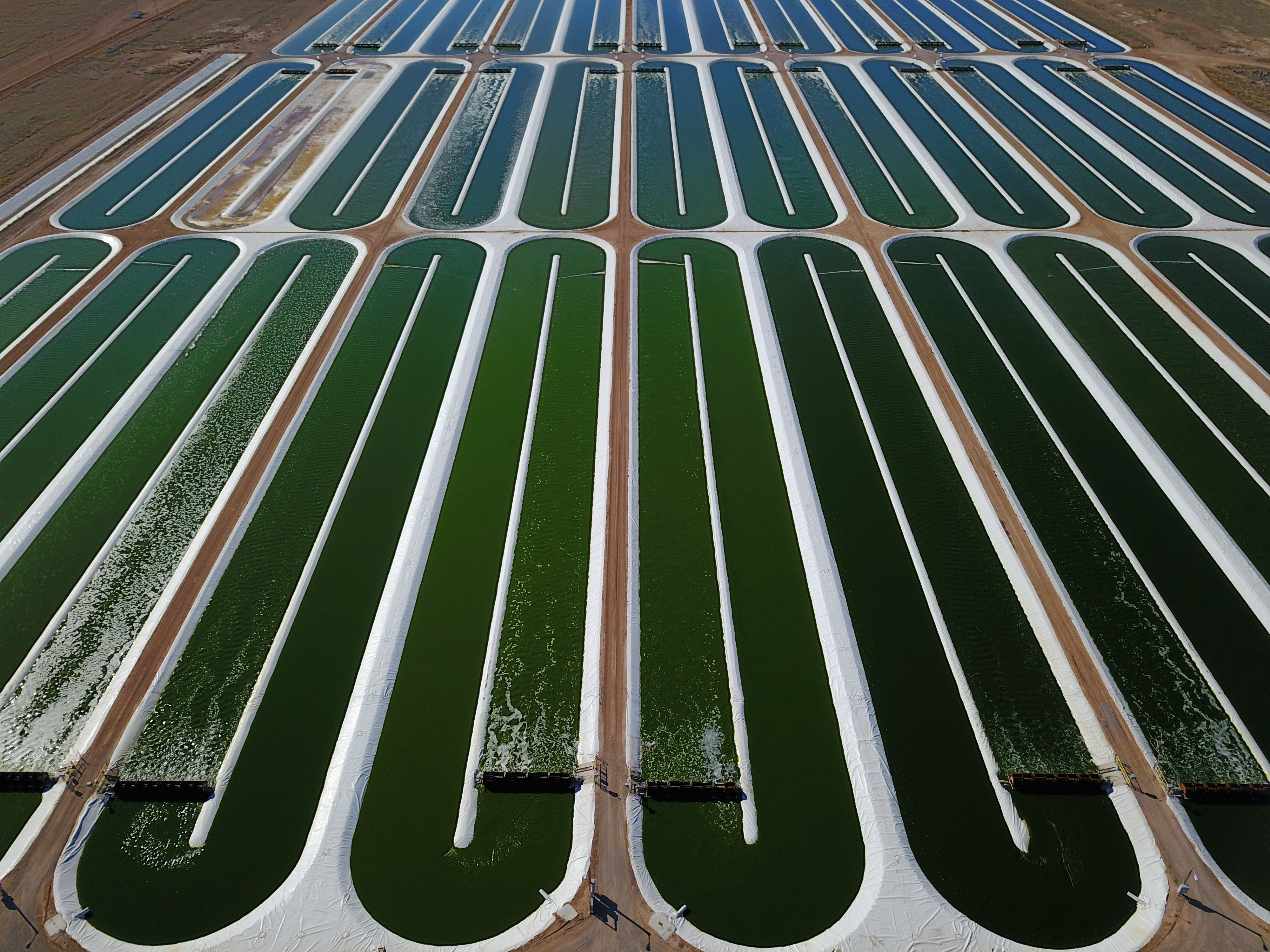

iWi grows its Nannochloropsis in 165 acres covered with vast, larger-than-football-field-sized saltwater ponds in the New Mexico and Texas desert. Unlike terrestrial plants, Nannochloropsis requires no soil and no freshwater. As a photosynthetic organism, its only real requirement is plenty of sunshine. It’s also surprisingly climate tolerant: it can survive anywhere that temperatures don’t drop below freezing for consecutive days or exceed 45°C for long periods of time.

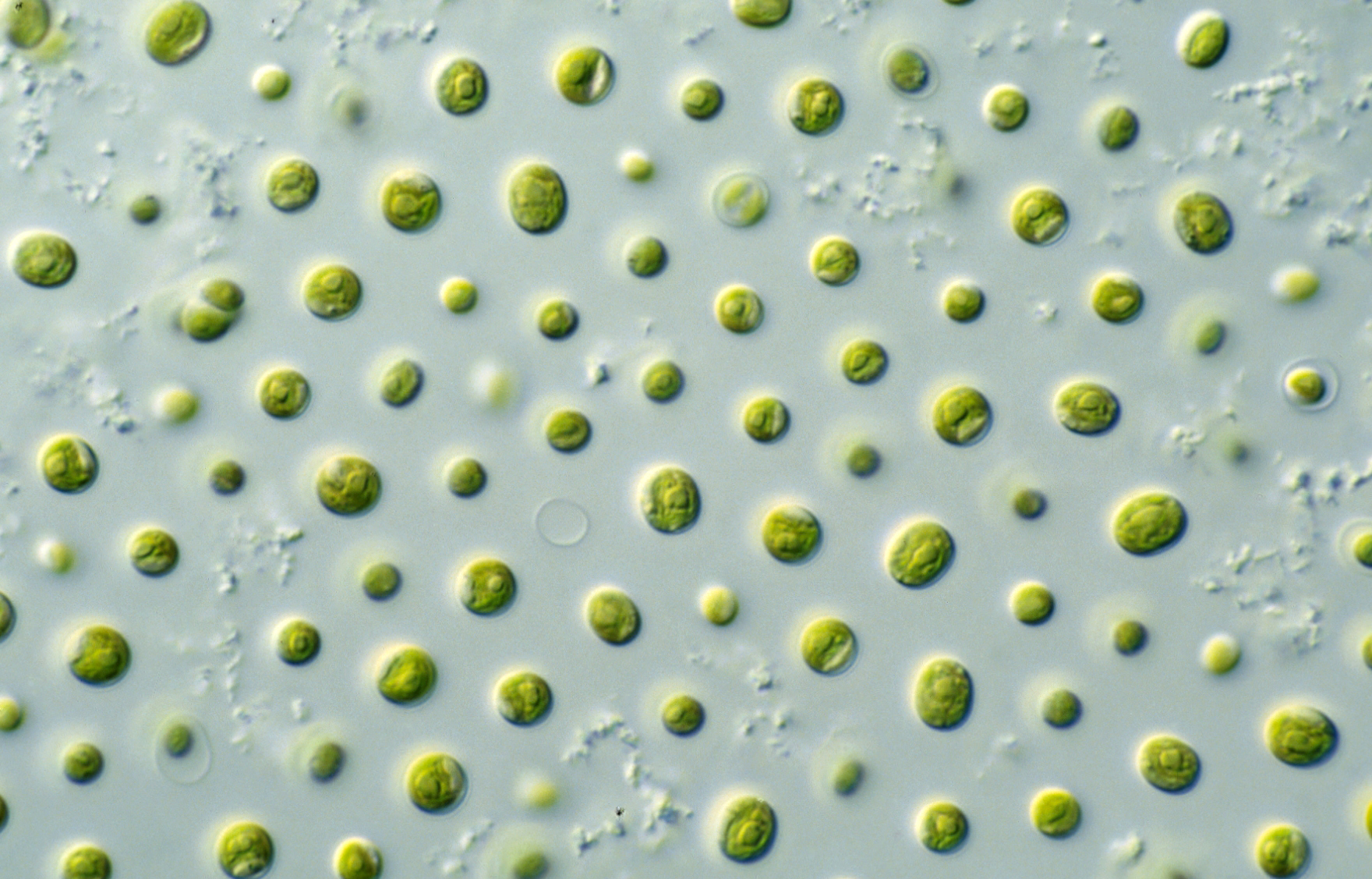

Microscopic view of Nannochloropsis.

iWi

Nannochloropsis happens to produce more essential amino acid per acre than any other farmed food — plant or animal — that the iWi researchers know of. Unlike corn, soy or many other traditional crops, iWi harvests the full plant rather than leaving behind roots, stem or leaves, which helps Nannochloropsis also pack about 300 times more essential amino acids per acre of land per year than peas. Put another way, the equivalent amount of essential amino acids produced by 150 acres of land used to grow Nannochloropsis would require 45,000 acres of land used to grow peas.

These off-the-chart productivity measurements are what first attracted Calatayud to algae. He previously worked as chief operating officer of a Spanish frozen food company that grew 700 million pounds of vegetables per year, from broccoli and corn to artichokes and green beans, and later became founder and chief executive officer of a similar company in the U.S. While he enjoyed the work, he found himself longing “to make an impact in the world and do something that would be meaningful for my kids and others.” It was at that critical moment that he discovered Nannochloropsis.

On top of all that, iWi’s alga is not contributing to climate change as a net CO2 producer. Microscopic marine algae produce half of the world’s oxygen, and Nannochloropsis is a part of that. “This, by far, was the most spectacularly efficient and productive crop I’ve ever seen on our planet,” Jakob says. “It’s using resources that otherwise would not be utilized, including non-arable land and salt water, and it consumes carbon dioxide and releases oxygen.”

Calatayud also emphasizes that while Nannochloropsis helps solve the problem of how to raise crops in an increasingly crop-unfriendly world, it does not compete with traditional crops for land, because traditional crops could not be grown there. One of the places where iWi currently grows its alga, for example, was abandoned by cotton farmers due to the high salt content of water and soil, a common attribute of arid land. “We use the land nobody else wants,” Calatayud says. “We’re not bringing an alternative to existing vegetables, but a highly-productive addition to common crops, as we are not competing with them for arable land or fresh water.”