Matteo Farinella

Meet Annie Jump Cannon, who cataloged and ranked over 300,000 stars by their hotness

A century later, her system is still used today

“In the house where I was born, there stood on the white marble mantel, a candelabra representing a gilded tree. At the base two children are about to waken a sleeping huntsman. Five outspreading branches support the candles, which are surrounded by glass prismatic pendants. I remember no earlier plaything than these prisms which were easily detachable. To hold one in my hands, to catch a sunbeam, and watch the brilliant prismatic colors dance over the wall was a delight to my youthful eyes. Even now I hold one of these pendants in my hands, and note that it is embossed with stars. Stars and prisms! How prophetic was this baby amusement of the profession which was destined to fill my life.” — Annie Jump Cannon

Annie Jump Cannon was born in 1863 in Delaware. Her father was a bank director and former state senator. Her mother taught her the constellations at an early age and encouraged her interest in astronomy.

Cannon studied physics at Wellesley College under Sarah Frances Whiting, a protégé of Edward Charles Pickering, director of the Harvard College Observatory. Whiting showed Cannon how to use a four inch telescope to observe the Great Comet of 1882. During college, a bout of scarlet fever took most of Cannon's hearing. She graduated from Wellesley in 1884 as valedictorian of her class and went back home to Dover to continue healing and study photography. Her skills allowed her to travel to Europe and eventually publish photos of Spain. After returning home, she tutored students in math and U.S. history, played organ at her church, and continued her photography.

The Great Comet of 1882, as seen from South Africa.

By Sir David Gill, South African Astronomical Observatory [Public Domain].

After 10 years of this and the loss of her beloved mother, Cannon was feeling unfulfilled and depressed. She reached out to Whiting, who was still at Wellesley, and procured an assistantship. Whiting prepared Cannon for advanced physics studies at Radcliffe College. There she was offered an unpaid internship at Harvard Observatory, still under Pickering's direction.

Teaching physics classes and completing astronomical observations gave Cannon a sense of purpose again. With her experience and academic background, Pickering made her the first female assistant to make astronomical observations at the observatory. Night after night she would record the slight fluctuations in brightness of stars by comparing them to nearby stars that were slightly brighter or fainter. She also compiled the observations of citizen scientists across the globe who made similar observations into a large series of tables that anyone could use called “A Provisional Catalogue of Variable Stars.”

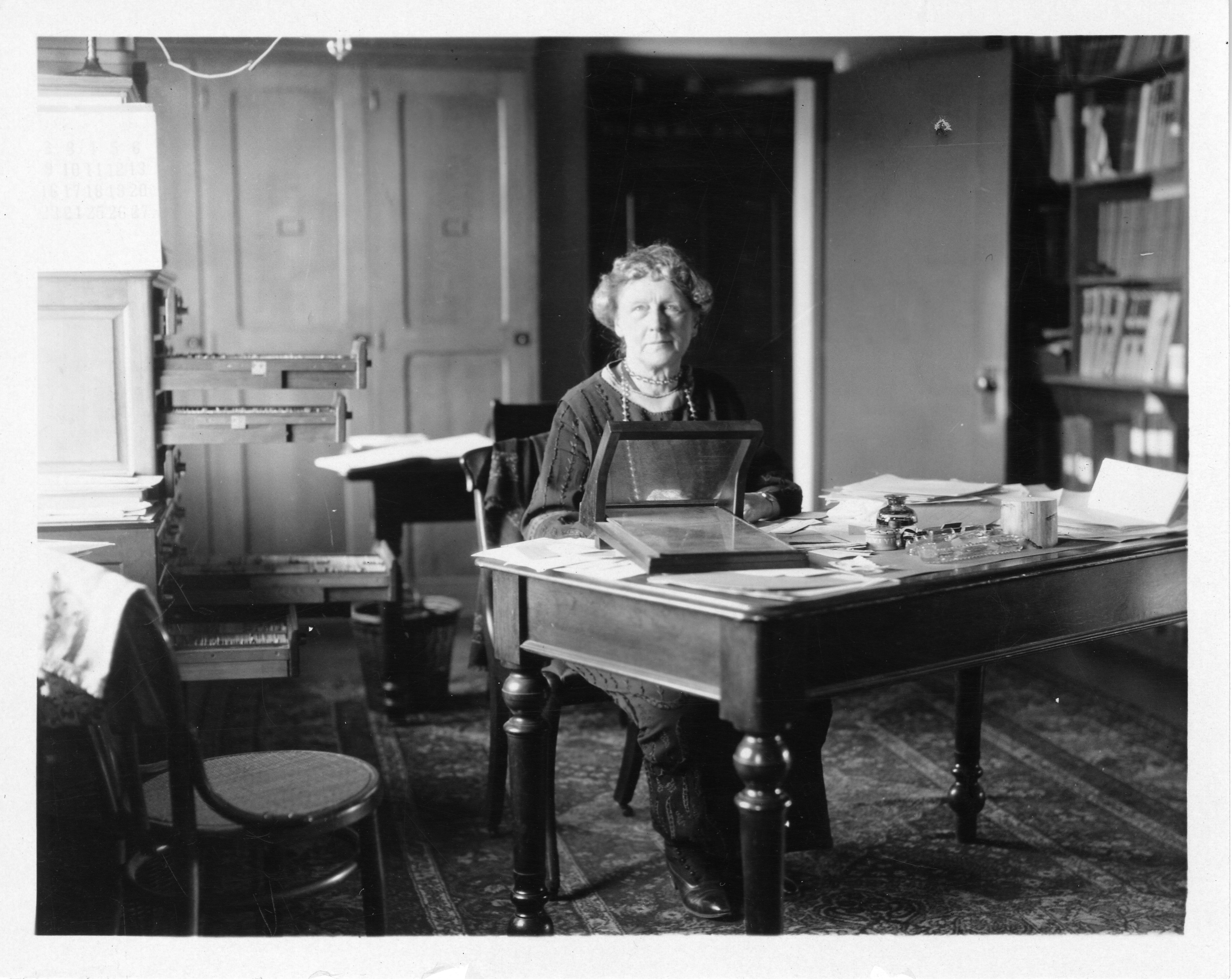

Annie Jump Cannon at her desk at the Harvard College Observatory.

Cannon is most known for classifying stellar spectra in a way that lead astronomers to understand why stars had different spectral patterns. Astronomers like Pickering used to observe one star’s spectrum at a time, passing the light through a prism in front of the telescope's eyepiece and drawing the rainbows they saw which were interrupted by dark, vertical lines from atoms within the star. With the invention of photographic plates — glass with a photosensitive liquid painted on — the spectrum could be recorded on a 1-inch square plate of glass but, now, in black and white. While this eliminated the task of drawing , Pickering found that installing the prism at the light gathering end of the telescope, instead of near the eye, sped up the process by creating an image that displayed the spectra for all the stars in the telescope's view on an 8”x10” photographic plate.

Matteo Farinella

Many of the Harvard Computers were tasked with classifying the thousands of spectra obtained using this method, but Cannon was by far the fastest. She would carefully place each photographic plate on a stand with a mirror at the base to catch sunlight that would illuminate the plate, revealing the hundreds of tiny horizontal bands of light where a star should be. The chemical makeup of each star is contained in the horizontal band of light that appeared on the photographic plates. The vertical dark lines that interrupted the stellar rainbow correspond to a specific element on the periodic table. Using a microscope, she would evaluate the patterns of dark vertical lines and call out a classification to an assistant who would record them. According to sources, Cannon could classify spectra in as little as three seconds — as quickly as her assistants could write them down.

Cannon devised a system that combined elements of the classification systems created by two of her fellow computers, Williamina Fleming and Antonia Maury. Fleming had devised a system with 15 separate classifications for the stars based on the strength of their hydrogen lines. Maury had a complex system of 22 separate classifications each with their own subdivisions and placed significance on the helium lines and their widths.

In Cannon’s system, she kept Fleming's lettered designations but reorganized them into just seven classifications. She, like Maury, gave precedence to the helium lines, so stars that had helium with missing electrons were first. The next set of stars had helium with all their electrons in tact. After that, the next category held stars with only hydrogen lines. In under three seconds, Cannon could look at a spectrum, assess the type of lines and their strengths, and choose from the 70 different possibilities for classification.

Cannon’s system is still used today. Astronomers later realized that her order perfectly ranks stars from hottest to coldest. All O stars, Cannon's first designation, are blazing hot stars with temperatures between 25,000-50,000 Kelvin while M stars, the final designation, are the coolest with temperatures less than 3,500 Kelvin.

Astronomers from around the globe recognized and celebrated her work. She was the first woman to receive an honorary doctor of science degree from Oxford University, and became an honorary member of the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS). She was nominated in 1919 for elevated standing as an Associate which would have put her at the same standing as men in the RAS. The Society members declined to do so. Harlow Shapley, who succeeded Pickering as director of the Harvard Observatory, nominated Cannon for the Henry Draper Medal of the National Academy of Science and wrote her a personal congratulatory announcement when she was awarded.

A portrait of Annie Jump Cannon in 1922.

By New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper [Public Domain]

The Association to Aid Scientific Research by Women awarded Cannon a $1000 prize in 1932, then dissolved claiming that since “women are given opportunities in research equally as men the objectives of the association have been achieved.” Cannon thanked them for the prize money but questioned their dissolution. She decided to use the money to endow the Annie Jump Cannon Prize which is still given every three years to a woman of any nationality by the American Astronomical Society. The first Prize went to Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin. Cannon had a jeweler, Marjorie Blackman, fashion a beautiful gold pin in the shape of a spiral galaxy for the prize. When she saw the result, she said, “Isn’t it the first universe ever made by a woman?” Even to this day, Cannon Prize winners receive an individualized piece of jewelry created by a different craftswoman.

In 1938, Cannon was finally recognized by Harvard as the William Cranch Bond Astronomer and Curator of Astronomical Photographs. Cannon reported to the Observatory six days a week until mid-March of 1941 when she became ill. She died in April of 1941, age 77.