Meet Antonia Maury, astronomy's renegade who changed the way we classify stars

Maury was part of a group of brilliant women known as the "Harvard Computers"

Antonia Maury was born March 21, 1866 into a true science family. Both her grandfather and her uncle were renowned scientists. She was helping her uncle, Henry Draper, in his laboratory as young as four years old. She was tasked with handing him the test tubes he needed for his chemistry experiment. By the time she went to Vassar College, she was primed to succeed in science.

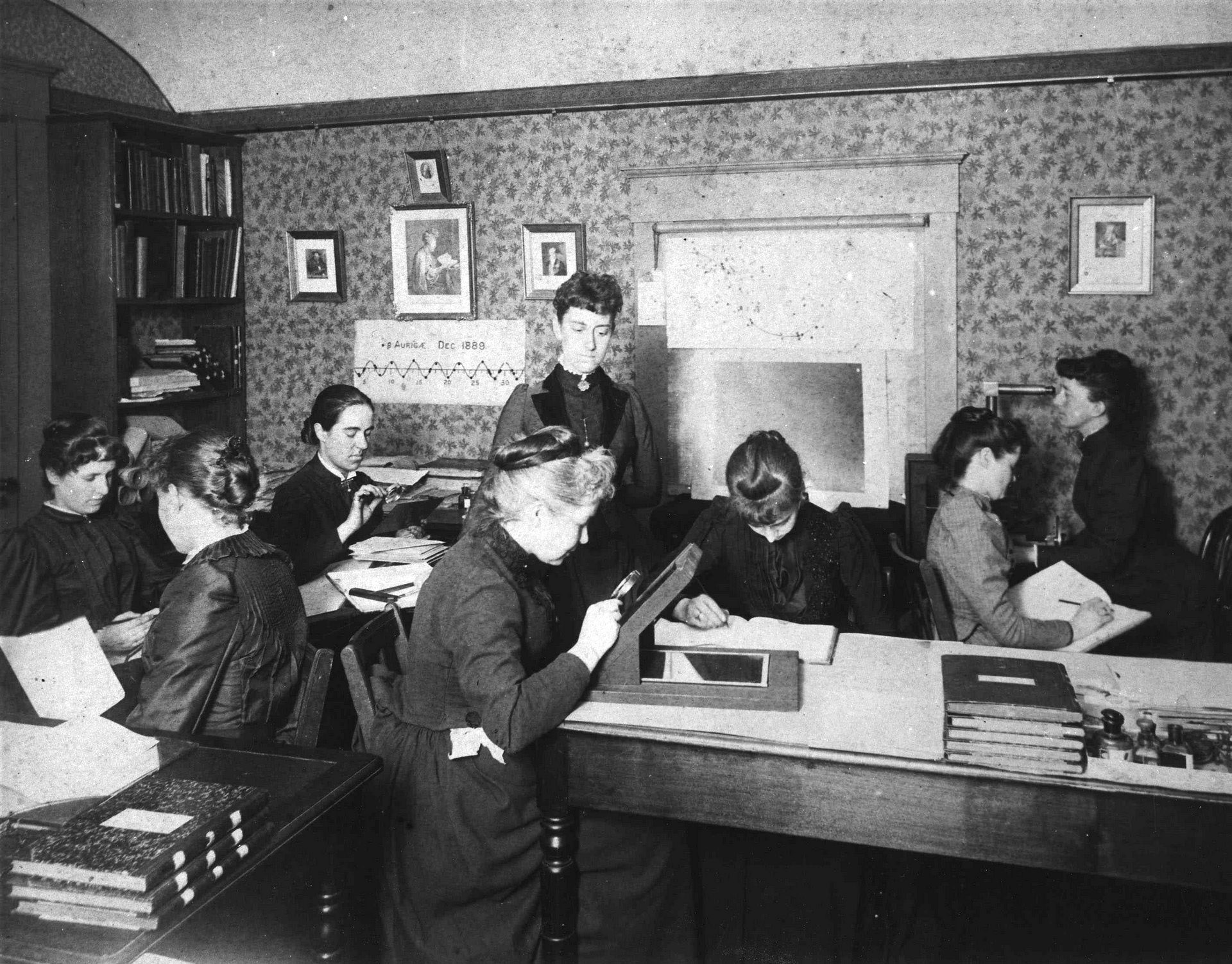

Antonia Maury was one of the women known as the Harvard Computers, alongside other influential astronomers, such as Henrietta Leavitt, Cecilia Payne and Annie Jump Cannon. These women were hired by the astronomer Edward Charles Pickering to classify the observations made by the male astronomers at Harvard College. This was the late 1800s and early 1900s, and in a reflection of how science-minded women were treated at the time, were also called "Pickering’s Harem."

Matteo Farinella

These brilliant women were hired as inexpensive labor, working for as little as 25 cents an hour. But Antonia Maury's accomplishments reflect the depth of talent these women had: She was a creative and independent scientist who made major contributions to astronomy, despite the challenges of working as – and sometimes, being treated as – a human computer.

Maury’s job was to work on a catalog of stars honoring her late uncle, the Henry Draper Memorial. Her uncle was a pioneer in astrophotography, and was the first person to photograph a nebula. He also took many photos of the moon, including the first photo taken through a telescope. Draper died in 1882 and his wife, Mary Anna Draper, donated money to the Harvard Observatory to create the catalog of stars in his honor.

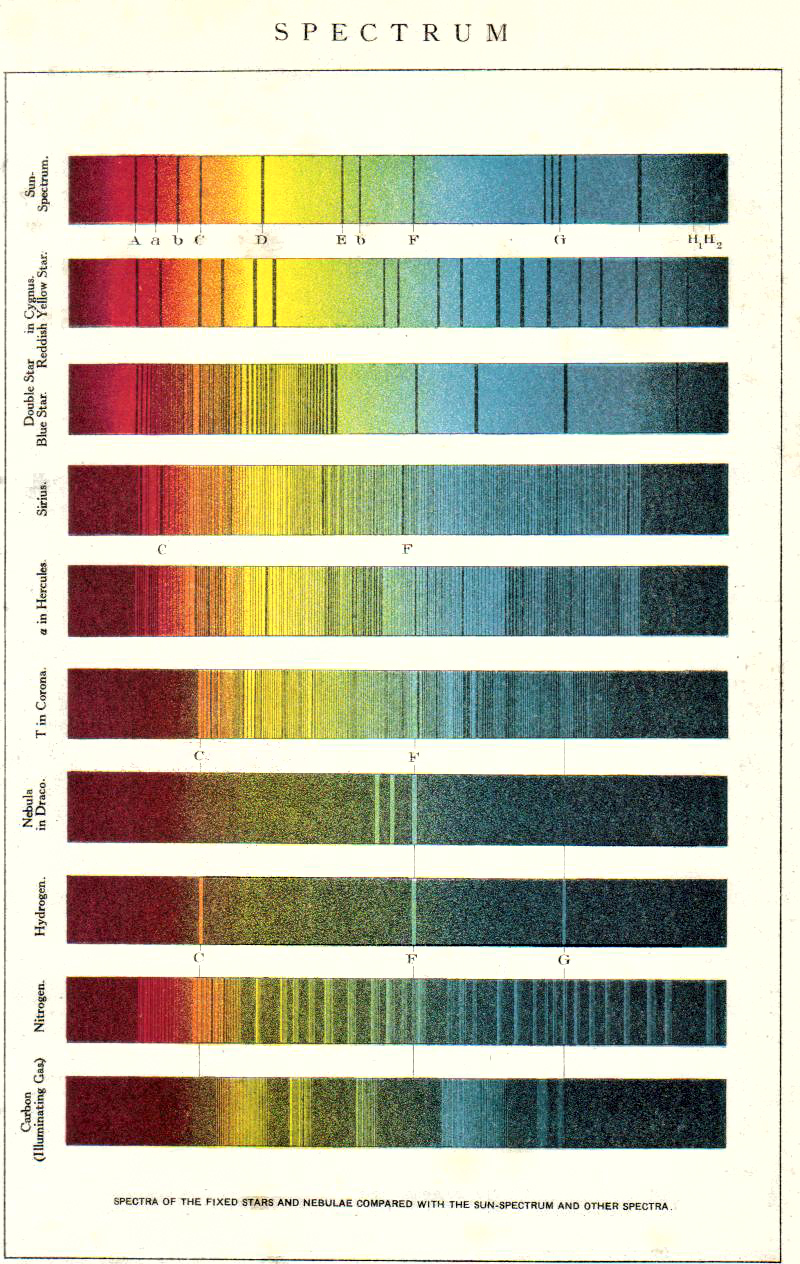

This included bright stars in the northern hemisphere, which Maury studied. The men in the observatory would point their telescopes at these stars and obtain stellar spectra (a measure of the light a star emits). Depending on what a star is made of, it won’t emit pure white light, which contains all the colors of the rainbow. Instead, only certain bands of color will show up on the spectrum. The colors that do and do not show up can tell astronomers something about the temperature and the size of the stars. For example, two lines in the yellow part of the spectrum, called D-lines, indicate a star contains sodium.

Maury did not like the classification system that Pickering and Fleming developed, which only included 12 types of stars. She decided to make her own. She reordered some of their classes, and added some of her own, resulting in a classification of 22 different types of stars, which were based on the combination of colored lines in the stellar spectra. The truly innovative part of her classification was the addition of lettered classes, a, b and c, indicating the brightness and width of the lines.

The astronomers known as the "Harvard computers," including Henrietta Swan Leavitt, Annie Jump Cannon, Willamina Fleming, and Antonia Maury

Harvard College Observatory on Wikimedia Commons

During her time at the Harvard College Observatory, Maury did not get along well with Pickering, the director of the observatory and her boss. He did not like that she created her own classification system, taking away time from her work on the Draper Memorial. Maury was described as an “independent renegade” by her colleague at the observatory Dorrit Hoffleit. Hoffleit surmised that she probably got away with this because of her family status, a perk the other women who worked with Pickering did not necessarily have.

Maury had an additional problem with Pickering: he would take credit for the women’s work, including hers. She discovered that Zeta Ursae Majoris, one of the stars in the Big Dipper actually consisted of two stars, called a double star. She found this through spectroscopy, the first time this method had been used to discover a double star. However, Pickering didn’t make her co-author on the paper describing this achievement, and only mentions her very briefly, saying: “a careful study of the results has been made by Miss. A. C. Maury, a niece of Dr. Draper.”

Maury left the observatory in 1891 for a teaching position in Cambridge, Massachusetts, following her disagreements with Pickering. But it wasn’t so easy to just leave. The Memorial Catalog for her uncle wasn’t finished yet. His widow and her aunt, Mary Anna Draper, was paying for the project and wanted Antonia to keep working on it. The two did not get along. Mary wanted Antonia to finish the work, but was happy to cut ties with her afterwards.

Antonia did return to finish the work at Harvard twice, in 1893 and 1895. Eventually her contribution to the catalog ‘Spectra of Bright Stars’ was published in 1897. On this work, Antonia was listed as an author and finally got her recognition. With it, she was also the first woman ever to publish a star catalog. By the time the catalog was published, she had already left the observatory and gone back to teaching. This would remain the case until 1918, when she returned to the Harvard Observatory as an adjunct professor.

Pickering died the next year, and Antonia got along much better with the new director. She published several works under her own name. During this time she studied Beta Lyrae, a star system in the Lyra constellation, and Upsilon Sagittarii, a star system in the Sagittarius constellation. Cecilia Payne, who worked with Maury, recalled: “She had a passion for understanding things. It was typical of her that she devoted years to the mysteries of Beta Lyrae and Upsilon Sagittarii, still incompletely solved.”

A diagram of the stellar spectra compared to the sun-spectrum, and others

Dodd, Mead and Company on Wikimedia Commons

Antonia Maury officially retired over 50 years after she started working at the Harvard Observatory, but continued her research –in addition to studying ornithology, natural history, and campaigning to save sequoia forests in the western US when they were threatened by timber companies – even after that. She passed away in 1952.

Antonia Maury published many influential papers during her time at the Observatory, such as her catalog on northern stars and her analysis of Beta Lyrae, and significantly impacted the field of astronomy with her work. Maury's enduring legacy is her classification system: Danish astronomer Ejnar Hertzsprung partially based his Hertzsprung–Russell Diagram, the main system to classify stars in modern times, on her c-characteristic. The official system of star classification adopted in 1922 by the International Astronomical Union used the letter c as well, to indicate narrow well-defined lines, a recognition of Antonia’s classification work. This system, with minor changes, is still in use today.