iWi

Acres of saltwater pools in the desert are growing an algae food revolution

High in protein and low in carbon footprint, algae is a breakthrough for feeding the world in a changing climate

“Algae? But... isn't that gross?” That’s what Rebecca White commonly hears from surprised people at her booth at trade shows, after the unsuspecting visitors find out the snack bar they just ate, and actually really liked, contains algae.

White is a research scientist at iWi, a nutrition company that runs one of the largest algae farms. She isn’t offering snacks filled with algae just to show people that the mossy greens can be added to food without making it taste or smell like pond water. The real mission is to discuss algae’s potential as a solution for a much bigger problem: the food security of our planet.

We will soon be running out of food. The projected population of the world in 2050 will require a 70 percent increase in food production, but we are already stretching our resources with the way we grow food today, a new United Nations report warned yesterday. Land is turning into desert, rising temperatures are cutting crop yields, and soil is becoming lifeless due to overuse. Seventy percent of the world’s available freshwater is used for agriculture and raising livestock. Livestock and the food they consume generate 14 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions from human-related activity, contributing to climate change, more droughts and land erosions. It’s a vicious cycle that experts say we are running out of time to break. “We need a farming revolution,” says Miguel Calatayud, the CEO of iWi.

Algae can be grown in areas where other crops won’t survive. They don’t need soil or freshwater. What they do need is a lot of CO2, which has led some to consider them for sequestering emissions from power plants. The algae’s excellent nutritional profile is another appeal. They have all essential amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, plus vitamins, minerals and essential fatty acids like omega-3.

Algae might not replace animal protein entirely but could help reduce our reliance on conventional sources of protein and reduce our carbon footprint. iWi wants to make it an everyday food by turning it into a protein shake, a powder you sprinkle over pasta, or to be mixed in anywhere else. “It can be a supplement. Or it can be an ingredient in basically anything,” White says.

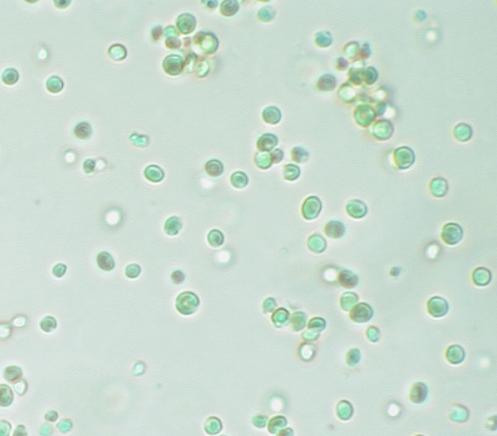

Nannochloropsis algae seen under a microscope.

It’s an ambition that has become sensible only after a long run of trial and error. After all, the US government recognized algae as a crop for the first time in the 2018 farm bill, and the agricultural know-how that exists for growing other crops is still in the making for this ocean dwelling plant. Scaling algae production is no easy task but iWi is employing a few creative tricks to make it happen. “We’ve been able to crack the code,” Calatayud says. Here’s how:

From the bottom of the food chain to a future food

iWi grows its algae in 48 ponds built in the deserts of New Mexico and Texas. Each bigger than a football field, the ponds are filled with the well water pumped from salty aquifers underneath. Farms previously on that land left after the aquifers became too salty. The watery green soup brewing in the ponds contains a million liters of a strain of algae called Nannochloropsis, with microscopic cells smaller than 5 microns.

To grow algae there are several concerns to address — first is to protect the crop from being eaten by other organisms before we get to it. “It is literally the bottom of the food chain in the ocean. Lots of things in the world eat it,” White says. “And so to be able to grow it, you have to be able to protect it from all the things that eat it without introducing anything harmful into the system.”

Algae farming is so new that there are no pesticides, insecticides or herbicides developed to protect algae (there are, however, lots of algaecides for killing it). That limitation, plus sustainability considerations, led the iWi team to turn to integrated pest management, which focuses on early detection and prevention of problems rather than fixing them after they’ve already happened. “We have figured out how to grow the algae in such a way that the ponds are an optimized environment for the algae to grow, and not much else,” White says. For example, when microscopic rotifers start to eat the algae, she controls them by introducing a sudden pH swing or tweaking the nitrogen source in favor of the algae and to the detriment of rotifers. “These little tricks around operational parameters allow us to grow the algae in open systems at very large scale,” she says.

iWi

Then comes harvesting, which has to be sustainable and energy efficient for algae to be considered an attractive food alternative. iWi uses a Zobi Harvester, a device recently developed under a grant from the Department of Energy. Touted as a breakthrough for the algae industry, this filtration-based system extracts algae from the water using low energy and no chemicals. The crystal clear water coming out the other end is then put back in the pond. “That's what significantly reduces our water footprint,” White says.

Harvesting comes in precise cycles so to not disturb the micro-ecosystem of the algae and halt their growth. Every time the density of the algae reaches a certain point, about 25 percent of the pond water is run through filtration to extract the algae. The remaining algae continue to replicate in the diluted water and the cycle repeats — it’s just like what you do with sourdough starter.

iWi then processes the algae to extract oil, which has high levels of omega-3 and is sold as supplements. What's left is proteins and carbohydrates, which the team is working on bringing to the market as protein products. “We're trying to make it as flavorless as possible,” White says. So far the extracted protein is good enough that White herself can’t detect it in foods, but the product still needs to clear the high bar of supertasters.

With the inclusion of algae in the farm bill, White and other algae farmers hope that federal grants will fuel progress in algae technology and elevate algae to a mainstream crop. It may take a few years, but the tiny green cells seem finally on a steady track towards the top of the food chain.