.jpg?auto=compress%2Cformat&crop=faces&fit=crop&fm=jpg&h=360&q=70&w=540

)

Matteo Farinella

Maria Kirch was the first woman to discover a comet, but her husband took the credit

Even 300 years later, Maria Margaretha Winkelmann Kirch is denied credit for her work

On the night of April 21, 1702, the astronomer Maria Margaretha Winkelmann Kirch started her routine observations. The previous evening, her husband, Gottfried Kirch, had found a variable star — one that rhythmically changes in brightness. She wanted to see it too, so Winkelmann Kirch lined up the telescope and prepared herself to stare into the lens at the fluctuating point of light. As she looked, she noticed a fuzzy smudge of light in her peripheral vision. She re-positioned the telescope and looked again. It was a new comet!

She woke her husband up to show him. The very next day, he wrote a report for King Leopold I describing the celestial newcomer. But Winkelmann Kirch’s name was left off the report. It wasn’t until just before Kirch's death in 1710 that he revealed his wife was the one who made the discovery, when he published the finding in the first journal for the Academy of Science in Berlin.

.jpg)

Matteo Farinella

Though not initially acknowledged, Winkelmann Kirch was actually the first woman to discover a comet — dubbed the Comet of 1702. (Two other astronomers in Rome independently found the comet hours before she did. So she is technically a co-discoverer.) But it seems the message still hasn't sunk in. While doing research on this comet, I came across a book Cometography: Volume 1, Ancient-1799: A Catalog of Comets,published in 1999, which describes the parabolic orbit of Comet 1702 H. In this text, the discovery is attributed to the two astronomers in Rome and ….Gottfried Kirch.

The Stars Aligned

Winkelmann Kirch had a nontraditional childhood for a kid in Germany during the late 1600s. Her father, a Lutheran minister, wanted his daughter to have the same education as men, so he oversaw her studies.

Winkelmann Kirch soon showed a strong interest in astronomy, and became the unofficial apprentice of Christoph Arnold, a farmer in Sommerfield, who was also a self-taught astronomer. After working with him for a few years, Arnold promoted her to his assistant.

Arnold was also friends with Gottfried Kirch, one of the most famous German astronomers of the time. Arnold introduced his assistant and Kirch, and they married in 1692. They had four children, who were all taught astronomy. The couple worked as a team, making observations and doing calculations to produce incredibly accurate calendars and positions of celestial objects — including planets, comets, and stars. Their calendars also contained the phases of the moon, sunrise and sunset times, and the timing of eclipses. When Kirch joined the newly created Academy of Science in Berlin in 1700, Winkelmann Kirch joined him there as his assistant. Two years later, she would discover her comet.

Venus and Jupiter in conjunction. Venus is the brightest, seen center lower right, Jupiter just to the left of it. The Little Dipper is at the top.

via Wikimedia

This wasn't Winkelmann Kirch's only contribution to astronomy. She went on to publish many well-received papers on a number of topics before Kirch’s death. In 1709, for example, she wrote a pamphlet on the approaching conjunction of Saturn and Venus with the Sun that garnered her respect within the German astronomical community. There was only one other woman —Maria Cunitz, a Silesian astronomer — in the entire Holy Roman Empire that was self published at the time.

Same credentials, different names

After her husband’s death in 1710, Winkelmann Kirch wanted to take over his position as the astronomer and calendar maker for the Academy of Science — as was common during that era in other trades, where widows often took over their husbands’ businesses. But the Academy of Science didn’t consider Winkelmann Kirch for the position until she petitioned them. She was allowed to continue her work while the Academy considered her petition — even receiving an Academy medal for her accomplishments. The president of the Academy, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, supported and encouraged Winkelmann Kirch, bringing her to the Prussian royal court to explain sunspots.

But the Academy didn’t want to set a precedent, and even the president’s word wasn’t enough. The secretary Johann Theodor Jablonski cautioned Leibniz that having Winkelmann Kirch "kept on in an official capacity to work on the calendar or to continue with observations simply will not do. Already during her husband's lifetime, the academy was burdened with ridicule because its calendar was prepared by a woman. If she were now to be kept on in such a capacity, mouths would gape even wider."

Kirch knew the reason she was kept out of the Academy was her gender. Some members went as far as advising her to return to her “distaff” and “spindle.”

Instead, the Academy hired an inexperienced man, Johann Heinrich Hoffmann, to take over the calendar making in 1711, while Winkelmann Kirch's petition was still technically under consideration. She and Hoffman worked independently during this time. Winkelmann Kirch published another well-received pamphlet predicting a new comet, as well as a defense of women’s intellectual abilities, where she argued that the “female sex as well as the male possesses talents of the mind and spirit." It was clear to Winkelmann Kirch that with experience and study a woman could be “as skilled as a man at observing and understanding the skies.”

After she was officially dismissed in 1712, Hoffmann fell behind in his observations, and the Academy asked Winkelmann Kirch to come back as his assistant. In a letter, she described her reluctance, saying “Now I go through a severe desert, and because … water is scarce … the taste is bitter.”

Persistence doesn’t always pay off

Fortunately, at the same time, Winkelmann Kirch was offered a position at the personal observatory of a friend, Baron von Krosigk. There, she reached the rank of master astronomer, and published another pamphlet on the conjunction of Saturn and Jupiter. She continued to make calendars there, with the help of her children, until von Krosigk’s death in 1714. She was offered a position as astronomer for the Russian czar in 1716, but refused so she could stay in Berlin with her son, Christfried, who had just been hired as a director of the new observatory of the Academy of Science.

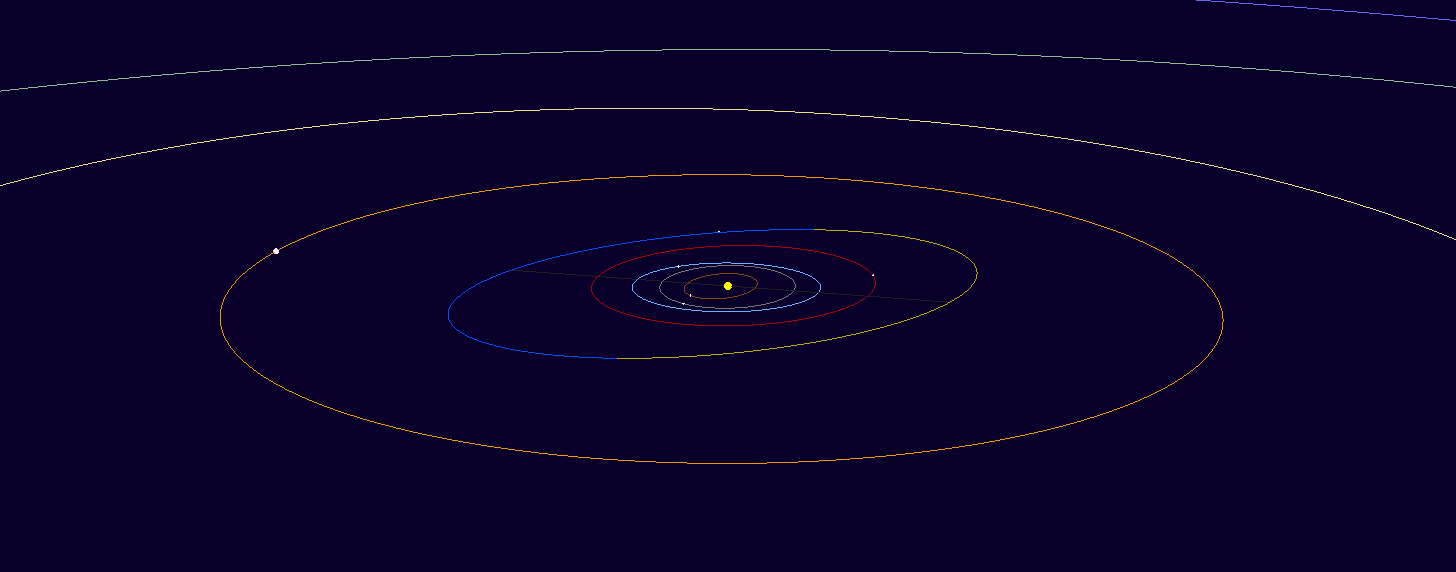

The orbit of the minor planet Mariakirch. The half blue, half yellow circle is the orbit of Mariakirch. It lies between the orbits of Jupiter (orange circle) and Mars (red circle).

The Minor Planet Center (MPC)

Winkelmann Kirch and her daughter, Christine, became Christfried’s assistants. Shortly thereafter, Academy members complained that Winkelmann Kirch made herself too prominent during public visits, and demanded that she stay in the background and not speak when visitors came around. She refused, and the Academy forced her to leave her position, saying they hoped she would stay close by so that “Herr Kirch could continue to eat at her table.” Winkelmann Kirch tried to continue her work in private, but no longer had access to the proper instruments. Her daughter stayed on as Christfried’s assistant at the observatory. Winkelmann Kirch died of fever in 1720.