People ask about my experiments on mice. The answers are … complicated

Behind most breakthroughs is animal research. Let's stop pretending otherwise

Being a neuroscientist means I have a lot of awkward conversations in Home Depot.

“What do you need it for?” the sales guy inquires after I ask where I might find Kapton tape, a special polyimide tape to protect electronics.

“… an experiment,” I sheepishly answer.

“Yeah, but like, what, exactly?”

I pause. I’m usually eager to explain that I’m a neuroscientist who wants to know how the brain combines information to make decisions. I started my career by measuring the activity in large sections of human brains, but these coarse snapshots didn’t answer my questions. My questions, like this eager employee's, required a more technical level of explanation.

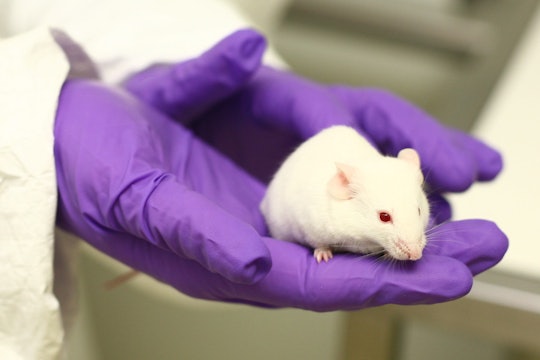

It’s a level of explanation I’m reluctant to offer. I do research with animals, and those parts of my job are hard to talk about. I need the tape to protect an electronic recording device that I’ve implanted on a mouse’s head, so that I can listen to hundreds of neurons in its brain.

“I need it to protect some electronics,” I offer the Home Depot guy. Vague, but sufficient.

“Oh, in that case, try the electrical tape selection on aisle nine.”

Several aisles and employees later, I leave Home Depot defeated and frustrated. They didn't have Kapton tape, and I had the same conversation with three different employees. I’ve had similar interactions about my job with awkward first dates, neighbors on long flights, and well-intentioned family members. In most cases, when you tell people you're a neuroscientist, they either assume you're the smartest person they've ever met or that you are one of those dreamy doctors who somehow never sleeps but always nails extremely intense brain surgery.

Uncomfortable explanations

Most people accept my vague answers to "what is it you do, exactly?" accordingly, as those of a distracted genius at work, but a select few aren’t satisfied with abstraction. They want to know – and as taxpayers, they have a right to know – what I do on a daily basis.

And that’s where I stumble over unpracticed and uncomfortable explanations.

In order to record from specific brain areas and cell types, many neuroscientists rely on studying animals, often mice. Mice aren't the smartest animals, but we do have an incredible toolbox that we can use to study specific cell types, receptors, or genes in them. In my second year of graduate school, I started recording from live neurons in mice, and it was immediately clear to me that this sort of research would give us a whole new understanding of brain function.

Still, the daily life of a neuroscientist doesn’t read like a headline of a popular science article. Some days, I spend hours performing a delicate surgery on a mouse, most recently to implant a recording device. Over the course of the next few weeks, I’m the mouse’s primary caretaker. I spend more hours with the mouse than I do with most of my friends. I observe its behavior and worry about its stress levels. I tinker with wires, watch neurons flash across the screen, and perseverate on what kind of tape I should use. And once that mouse has helped us figure out something more about how its brain works, I respectfully euthanize it, and move on to the next experiment.

Research like mine is tough, but it provides unprecedented insight about the role of specific cell types in the brain. Some of these neurons, the ones that silence neighboring cells, are thought to be dysfunctional in disorders like schizophrenia. With this type of research, we've learned how different receptors and neurons tune our reward system, changing how we conceptualize and treat addiction. The data we’ve collected have taught us that the computations in the brain are wonderfully intricate – insights that are informing computer science and artificial intelligence every day.

I’d like to think that, as a society, we’ve made a collective decision that working with animals is worth it, and that this would make it easier to discuss my research with random strangers. Unfortunately, this isn’t the case.

One time, I got into a deep conversation with a very inquisitive Lyft driver, who was completely baffled and a bit distraught by the fact that I used mice in my experiments. Of course, there are also more outspoken animal rights activists. Each year, the Salk Institute has a 5K run to raise money for research – as a PhD student, I saw the protesters, read their signs, and heard their chants.

As a result of these sorts of interactions, I’ve told very few people about the nitty gritty details of my job.

It's difficult to hide any aspect of yourself, whether it's a part of your identity or something that you do everyday. Academics are known to struggle with mental health, and part of this is likely because of the opaque lives many of us lead. Science is a noble pursuit, but it can be difficult to feel like an honorable soldier when nobody back on the home front understands our experience.

The best thing scientists can do to grapple with the hidden weight of doing animal research is to talk more about how we conduct our work and how it makes us feel, both with other scientists as well as with civilians. We need to be able to talk about the squishy, emotional, sensitive parts of our daily lives, as well as the science. What we don't talk about can get buried in our psyche and undermine our ability to lead happy, productive careers.

In my ideal world, we would all have a shared understanding about what research really is, warts and all. Behind almost every science or medicine headline is an animal model, and many people who conducted research on that model. We don’t only learn things about the brain by conducting thought experiments or behavioral research; we need experimental data about what neurons are doing. We need to know how the whole endlessly complicated thing develops, changes, and breaks. We simply can’t do this research in humans.

I may not have the perfect response in the moment to why I need a specific type of tape, but I’m working on it with the hope that it will meet a sympathetic listener.