The most cost-effective ways to fight climate change are literally under our feet

A new study says forests, swamps, and soil are the cheapest ways to help save the planet

In 2015, most of the world came together in a rare act of collaboration and set an ambitious goal to limit global temperatures from rising no more than 2°C. Each country, from China to Belgium to Peru, outlined a path to best reduce emissions, according to their people, geography, and economy. The US has declared its intent to exit the agreement, but so far hesitated, and many states plan to find their own solutions independently. Their options include low cost, natural mitigation plans that do not any require major technological breakthroughs.

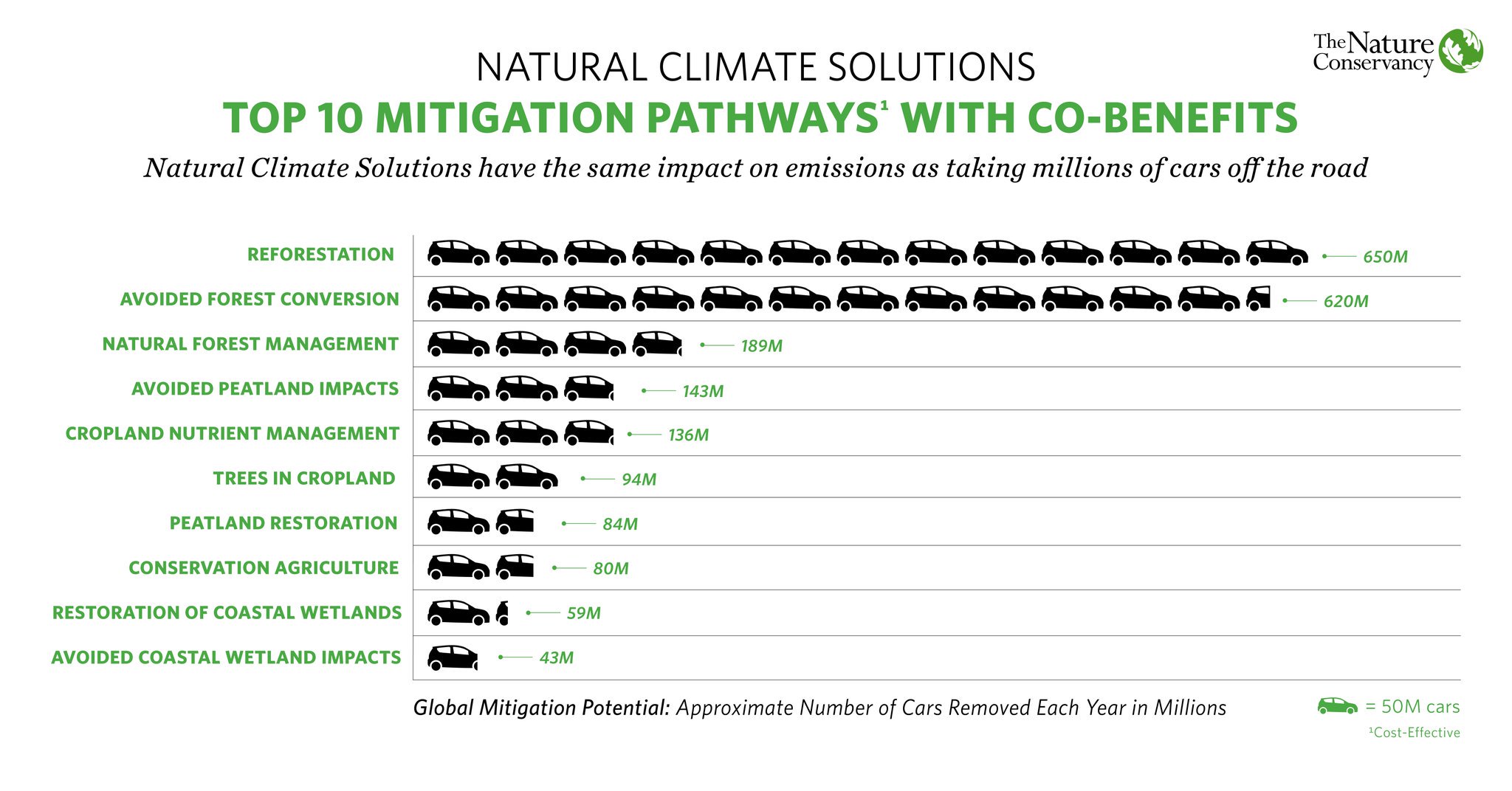

These plans have become all the more appealing in the wake of a recent paper that breaks down the latest and most successful natural climate solutions, from growing trees to harnessing the power of soils. If implemented between today and 2030, the methods could remove more than a third of the atmospheric carbon we need to reach our climate goals in a cost-effective way.

To state the conclusion upfront: nature can help us limit global warming to 2°C, through conservation, better land management, and restoration of ecosystems. And we can do it at a lower cost than most other solutions.

The researchers, led by Bronson Griscom and his colleagues at The Nature Conservancy, found that nations can get the most bang for their buck by concentrating on reforestation and limiting deforestation, in the US and across the world. Additionally, nations, states, and cities have many opportunities to store carbon in agricultural soils.

To assess these natural solutions and their potential effectiveness, Griscom and colleagues carried out an analysis of most of the world's current, land-based climate mitigation solutions. The project, the most comprehensive of its kind to date, is truly an effort built on the shoulders of giants, bringing together data from the latest scientific studies and climate models.

Rather than testing specific hypotheses or asking research questions, Griscom and colleagues assessed 20 discrete climate mitigation options within the land sector, strategies like conserving forests, restoring wetlands, and planting cover crops. Their assessment fills in previous knowledge gaps, taking into account the need to safeguard food, continue fiber production, and protect biological diversity.

Nor did they ignore economic realities. To appropriately constrain their model by real-world demands, the authors estimated the potential mitigation plans using two cost estimates for removing carbon from the atmosphere, using dollars and megagrams, or the equivalent of just over a ton. The high estimate is $100 per about a ton of CO2 equivalent, and the low $10 per ton of CO2 equivalent.

Accounting for these costs, the authors then created global maps of where to implement the 10 most promising solutions. Most notably, the authors provide a global dataset of reforestation opportunities, and how they are constrained by food security and biodiversity safeguards. This dataset can help countries target their efforts to where they will have the most positive impact.

Forests, soil, grasslands, and swamps

We can start with what we know: Trees remove a lot of carbon from the atmosphere through the process of photosynthesis, nature’s way of turning waste into value. When trees grow, they use carbon from the atmosphere to build tree trunks, branches, and roots, locking away carbon molecules in solid form. The more trees we grow, the more carbon we remove from the atmosphere, so it should come as no surprise that the cheapest, most effective natural climate solution is reforestation.

Not to scale

In fact, natural climate solutions that include reforestation, managing forests better, and soil conservation practices, can provide up to 37 percent of the needed carbon removal between now and 2030, an absolute must to reach ambitious climate goals. And natural climate solutions can deliver these climate benefits at a low cost: a third of them cost at or below $10 per ton CO2.

That’s substantially lower than the estimated social cost of carbon, essentially the potential cost of dealing with carbon emission impacts, from health to environmental and economic (approximately $30 per ton of CO2 emitted). And most natural climate solutions deliver other benefits, including flood mitigation, water filtration, enhancing soil health and productivity, fostering biodiversity, and enhancing the resilience of natural systems. Not bad for $10 per ton CO2.

Other low-cost options for climate mitigation include restoring grasslands, reducing fertilizer usage on farms, and planting legumes that can make their own fertilizer (called nitrogen fixers). Another option is to plant trees into places with little agriculture, which has the added benefit of improving air and water quality and providing habitat for birds.

With farming, it all comes down to soil: any practices that improve soil health rebound to the climate, because soils store a lot of carbon. Adding materials like biochar to soil could create a lot of mitigation potential, though that has yet to be well-demonstrated beyond research settings. We could also improve livestock practices; shifting grazing, feed supplies, and when herds move across the landscape could increase soil carbon and reduce methane emissions.

.jpg)

'Let's trap carbon!'

Wetlands are not nearly as extensive as forests and grasslands, but they hold a lot of carbon, and they filter and clean water, helping build more climate resilience. Preserving wetlands is less expensive than restoring them, but both their conservation and restoration offer excellent and relatively low-cost opportunities for climate mitigation.

The authors also included new research results that report the potential to store carbon in soils, through agriculture practices that do not till the soils and methods of livestock grazing that promote healthy soils. These two practices have traditionally been excluded from global analyses of this scale but are important in agriculture. The authors also applied what's called "the Delphi method" of expert counsel, asking 20 experts to give their opinions – essentially “phoning a friend” or crowdsourcing to ensure their methods made sense in the real world, and not just in a mathematical model.

This new paper stands apart from others in that its authors combined several factors in their analysis, including cost and real-world feasibility, meaning their results highlight cost-effective solutions. It also takes into account food production and gauges solutions to minimize negative consequences.

Nor is the paper only about mitigating climate change. The team, although searching for solutions, do not minimize the enormity of our challenge; the authors treat readers as adults who can face climate change honestly and move forward with concrete solutions.

Understandably, Griscom and colleagues were not able to account for potential breakthroughs in technology or industry, like the widespread adoption of perennial crops, like Kernza, instead of farming annual crops. The options examined by Griscom's team are by no means the only ones we have to choose from, but the authors have laid out a robust menu of options for how nations, states, and cities can enlist ecosystems as solutions to climate change.

The largest question that the researchers did not address, even with a clear set of low-cost, currently available solutions, is how we might enact these projects. That "how" is critical, especially since there are often many different paths to the same outcome. The new paper gives us targets, but does not provide a guide to action. Ultimately, the onus falls on us to choose our paths of addressing climate change. Land stewardship is not a bad place to start.