NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell

Opportunity, thanks for inspiring a new generation

We wouldn't be here without you.

“When did you first decide to be an astronomer?”

For years, I answered this question with the conventional story about cold nights looking through my telescope at Saturn’s rings. I then went on to college, majored in physics, went to graduate school for my PhD in astronomy and voila, my origin story is complete. But after learning last week that NASA’s Opportunity rover mission on Mars had ended, I remembered an earlier spark of inspiration. I was 12 when Opportunity, and its twin rover Spirit, landed on Mars in January 2004. I was glued to the television, watching the NASA control room erupt in applause when they received the first communications as the rovers bounced across the Martian surface. When the first photographs of that alien landscape appeared, I was in love. The sense of exploration is what captivated me and I knew then I wanted to explore space.

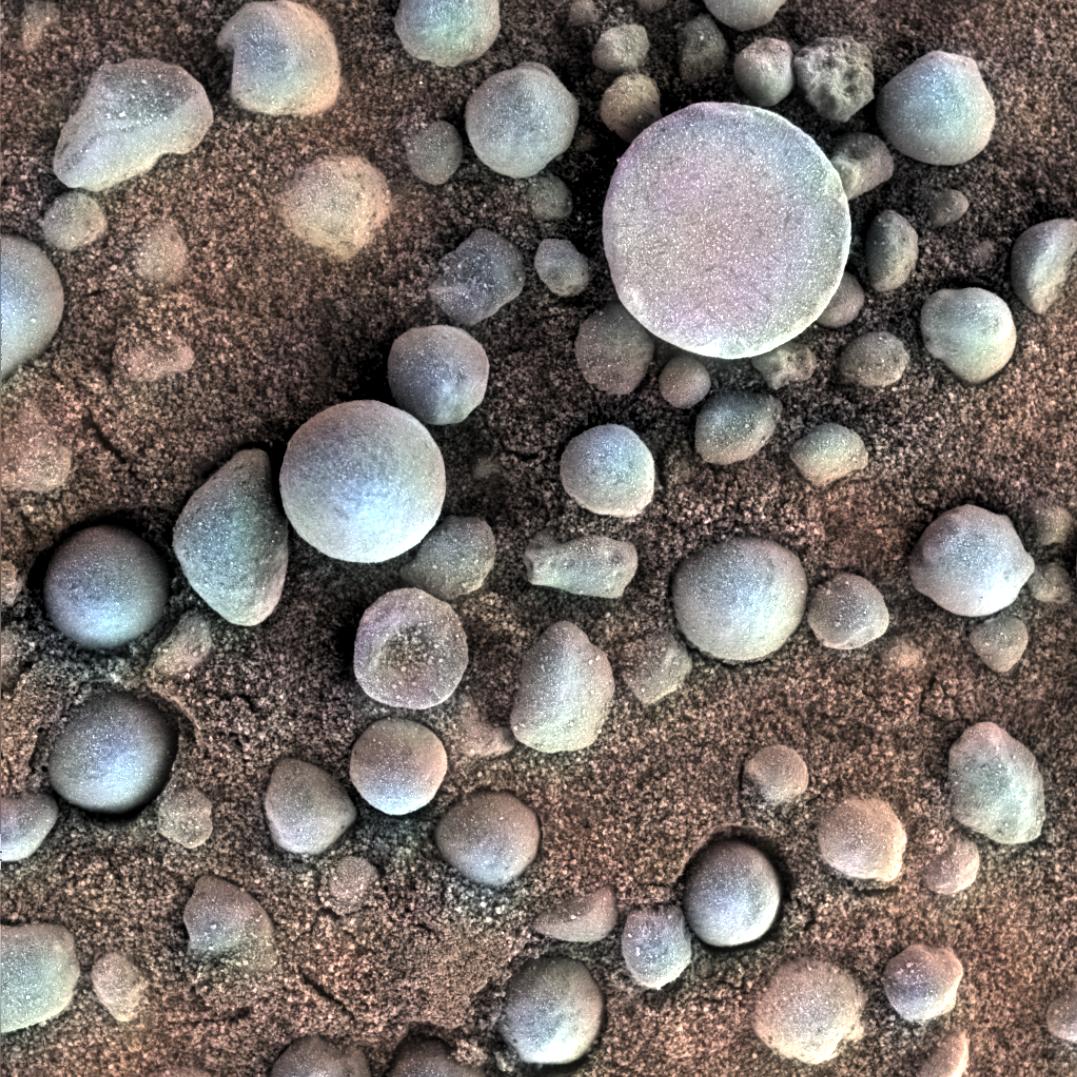

Opportunity unfurled its landing cocoon and rolled out onto Martian soil to begin a 14-year, 28-mile journey of discovery. The main scientific goal of the mission was to find out whether water once flowed on Mars. Immediately upon venturing out, Opportunity found its first evidence of ancient water: Round rocks the size of peppercorns, nicknamed “blueberries,” were strewn all over the rover’s landing site. Closer inspection revealed that these rocks were full of a mineral called hematite, which forms similar rocks in watery environments on Earth. The discovery of the “blueberries" was Opportunity’s first clue that Mars was once wet.

Blueberries.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell

In 2011, seven years after it landed, Opportunity found a smoking-gun that water once flowed on Mars. On the rim of a crater, the rover spotted a bright white vein of gypsum. On Earth, these veins are deposited by mineral-rich water that flow through underground cracks in rock. Opportunity had driven for 20 miles before finding this piece of rock, about the width of your thumb and the length of your forearm, which provided the clearest glimpse yet into the watery past of Mars.

Gypsum.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/ASU

Amid the detailed investigation of Martian geology and chemistry, Opportunity captured iconic photographs that showed us Mars as a true world, a place we could someday walk ourselves. A panorama of a crater filled with scalloped sand dunes. A movie of Martian clouds lazily floating by on an October afternoon. A look back at the rover’s wheel tracks after being stuck in deep sand for over a month. The rover even took selfies, reminding us of the feat of engineering that was responsible for all these incredible images. All told, Opportunity took over 200,000 pictures and outlasted its twin Spirit by 8 years.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell

Opportunity finally lost power in June of last year, blanketed by the worst dust storm it had ever seen. After months of attempts to revive the rover, NASA officially declared it dead last week. Perhaps even more important than its scientific discoveries, Opportunity’s greatest legacy is the inspiration it sparked in so many kids. This is not just wishful thinking used to justify taxpayer funding of such missions in the future. There are actual scientists and engineers on the Opportunity rover team who were inspired to pursue their careers by the launch of that mission 15 years ago. When we fund a mission like Opportunity, we are not just funding scientific discovery. We are funding inspiration and wonder. I can attest to that. If I hadn’t been watching as Opportunity reached Earth, I may have never asked for a telescope for my birthday. I may have never begun my own quest of exploration, leading me to study the birth of stars a thousand light years away on my way to a PhD in astronomy.