Via Wikimedia

How the pelvis, and not bipedalism, gave humans their narrow hips

The anatomy of our pelvis is a result of an evolutionary trade-off, but perhaps it's not the one we thought

Giving birth is generally a difficult process for humans, often requiring long hours of labor and help from other people, but this doesn't seem to be the case for our closest living relatives, the African apes. The obvious explanation is that we give birth to relatively large, big-brained babies through a pretty narrow pelvic opening, while the opposite is true for our ape cousins. But why we ended up in this painful evolutionary predicament is still an open question, one that anthropologists recently teamed up with an engineer to try to answer. It turns out, we might've been focusing on the wrong reason for that narrow pelvis all along.

For decades, the conventional wisdom among anthropologists was that the anatomy of the female pelvis is an evolutionary compromise between the demands of our unique style of locomotion, bipedalism, and the demands of giving birth to big babies. A narrower pelvis was thought to make walking and running more energy-efficient, while a wider pelvis would allow for a larger birth canal. This trade-off is often called the "obstetrical dilemma."

The supposed dilemma has been challenged recently, in part because the fields of paleoanthropology and human evolutionary biology are becoming more diverse, with a greater variety of lived experiences being brought to bear on key questions about our evolution. Anthropologists have now experimentally demonstrated that a person's sex doesn't make a difference to their running or walking efficiency and that effective bipedal locomotion isn't impaired by a wider pelvis, for example. Additionally, human birth canals aren't uniform in size and shape around the world; if this trade-off was so critical, we would expect less variability.

Big headed babies and a narrow pelvis mean Homo sapiens have a particularly difficult time giving birth

Christian Bowen on Unsplash

So, if locomotion isn't the main pressure driving selection for a narrow pelvis, what is? A paper published this year in PNAS suggests that pelvic floor function might actually be behind it, instead.

The pelvic floor is the set of muscles and connective tissue that forms the base of the pelvic canal; if the bones of your pelvis are the sides of a bowl, the pelvic floor is its bottom. The pelvic floor plays a really important role in supporting our internal organs and the weight of a large fetus and maintaining continence (your ability to control your bowels and bladder).

.jpg)

Becker1999 on Wikimedia Commons

The size and shape of a person's bony pelvis dictates the size and shape of their pelvic floor, and there seems to be a bit of a Goldilocks situation happening here – it can't be too big or too small. The pelvic floor needs to be strong enough to support the weight placed on it and deal with changes in pressure within the abdomen caused by normal activities like coughing, while also being stretchy enough to allow for birth. The size and thickness of the pelvic floor is where the trade-off between strength and stretchiness happens.

The new study came to this conclusion by testing the "pelvic floor hypothesis" using a series of mathematical models informed by experimental data from MRIs. The modeling technique allowed the researchers to vary the size and thickness of a hypothetical pelvic floor, and measure how much stretch and stress it experienced at different sizes and thicknesses. They found that the pelvic floor bent out of shape more, and the tissue experienced greater stresses and stretches, as its size increased. Increasing the thickness of the pelvic floor only partially compensated for this and came with its own downsides, like the fact that a thicker pelvic floor would require much higher abdominal pressure for giving birth and possibly also for pooping.

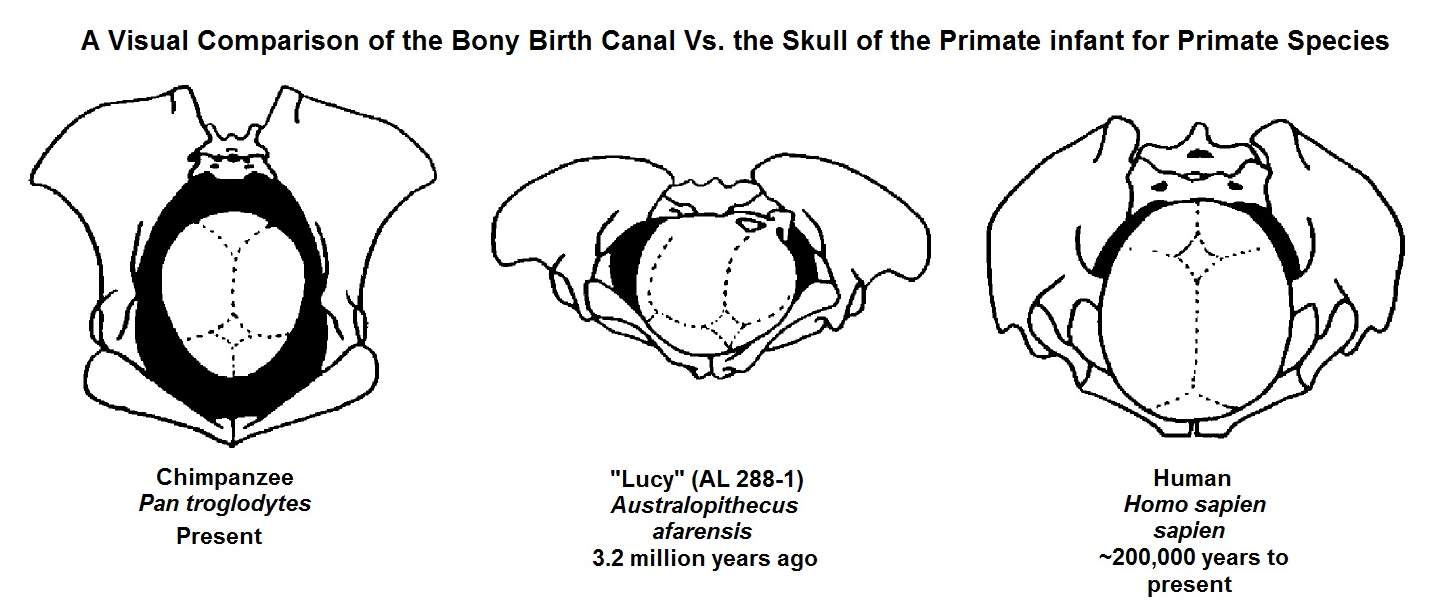

Human infants have much larger skulls, and must pass through a much narrower pelvis, than other apes or hominids.

ArchaeoMouse on Wikimedia Commons

These results support the "pelvic floor hypothesis" and complicate the previous idea that the main evolutionary trade-off driving human pelvic evolution was between a narrower pelvis for efficient locomotion and a wider pelvis for a more spacious birth canal. Instead, it looks like a major pressure driving selection for a narrower pelvis was actually the task of suspending a sufficiently supportive pelvic floor – one still allows for birth, but prevents rupture and prolapse.

Ultimately, this study serves as a reminder that there's a lot more to our evolutionary history than bones alone can tell us, and that it will only continue to come into greater focus when people with new, different perspectives can weigh in on the stories previous researchers have told about our shared human past.

Really enjoyed this article! I’m so intrigued by this evolutionary playoff between strength of the pelvic floor muscles and being stretchy enough to allow for birthing. I was wondering, how do you think the development of medical techniques/healthcare such as caesarean section or anaesthesia could have possibly influenced the evolution of these two factors? Also, do you think in the future, MRI scans to assess pelvic floor muscle composition could be used a detection method for understanding if it could be potentially safer (or less painful!) for women to have an elective caesarean section. Although I’m not sure how realistic, feasible or recommended this would be in reality! Really interesting evolutionary biology, thank you!