Instead of climbing into an MRI machine, a new test asks children to just blink

We can now bypass MRIs and instead use trace eyeblink conditioning to measure brain function

By Quinn Dombrowski on Flickr.

The hippocampus is a region in the brain where memories about the space around us and how to navigate it, as well as memories about events that affect our lives are formed. But testing the relationship between the brain and behavior in young children has been challenging in the past, which is why we need novel methods.

Measuring brain function in young children is often challenging because the tools we normally use can intimidate children. For example, a young child may feel scared or restless in an MRI machine, resulting in either unusable data or causing the child to drop out of the study.

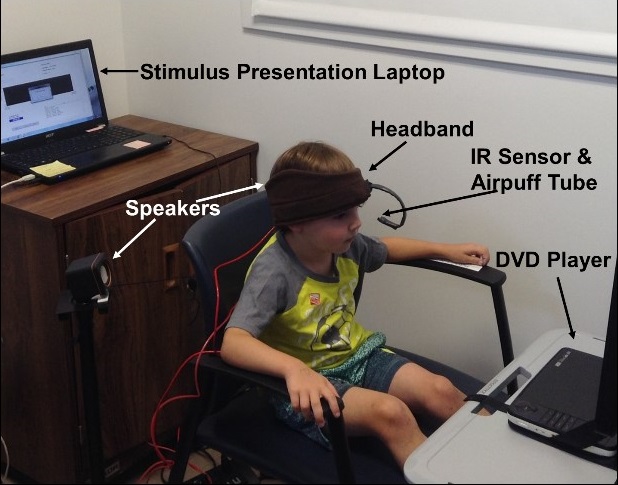

That's why in a study out earlier this year, my fellow researchers and I used trace eyeblink conditioning (EBC) — a novel way to indirectly measure the hippocampal function — to assess spatial and episodic memory abilities in children between the ages of three and six. Because EBC is safe and non-invasive, it is an ideal way to examine learning, memory, and brain function in children.

The trace eyeblink conditioning (EBC) method in action.

Vanessa Vieites

In EBC, children are presented with a series of auditory (i.e., tones) and tactile (i.e. airpuffs to their eye) stimuli. What makes EBC rely on the hippocampus is that the tones and airpuffs are separated in time by 500 milliseconds, and that time lapse, while seemingly insignificant, can be difficult for preschool children to remember. Those who develop a learning response will blink at the sound of the tone alone, thinking that the airpuff will follow shortly.

In our study, we also asked children to take three additional tests. One was a spatial reorientation test, in which they searched for a hidden object in a rectangular room with 3 white walls and one red wall. The second was an episodic memory test, in which they memorized sequences of pictures. Lastly, children completed a processing speed test, which does not rely on the hippocampus.

Children who were better at detecting the predictive nature of the tone were also better at using the geometry of a room to locate a hidden object, regardless of age. These findings suggest that hippocampal function underlies the use of, specifically, geometric strategies for navigating, even in young children.