Lab Notes

Short stories and links shared by the scientists in our community

Bacteria can live without food for over 1000 days

Nearly three years without food drives innovative survival strategies

Bacteria survive and thrive even in the harshest environments. Scientists have characterized species thriving in Antarctica, and even in deep-sea oil wells. Now, a study published in PNAS in August found that many bacteria can live without food for more than 1000 days.

Using 100 different types of bacteria, researchers tracked their growth and survival over time. This allowed them to model how long the community could eventually live. Early on, many of the bacteria within a population died out. But the remaining bacteria ate these dead cells. Afterward, the rate of bacterial death slowed as they adapted to low-energy conditions. Over these 1000 days, natural selection drove innovative survival strategies.

The study shows that many bacterial species can survive far harsher conditions than scientists would have predicted. Their persistence could allow them to survive thousands of years. It is also important for learning why certain recurrent infections are difficult to cure, and provides more credence for researchers focused on findings signs of microbial life on Mars. After all, if most microbes can survive without any food, they might be able to persist in even harsher environments on other worlds.

Freshwater zebra mussels deal with microplastics surprisingly well

The invasive species may hold lessons for others

Wikimedia (PD)

Microplastics are found in marine and aquatic environments worldwide because they are used in personal care products, and result from the breakdown of larger plastic waste. Many researchers, policy makers, and scientists in the the private sector are concerned about how microplastics affect the environment, ecologically and commercially important species, and human health.

The effects of microplastics on freshwater species are less well-studied than those in marine species. In a study published in Environmental Toxicology, researchers from Goethe University, the Federal Institute of Hydrology, and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology tested zebra mussels found in a German lake for various signs of microplastic toxicity and connections between toxicity and physical traits. Zebra mussels are a freshwater mollusk native to Russia and Ukraine, that are now considered an invasive species in Europe and North America. The researchers also repeated some tests with duck mussels and Chinese pond mussels to compare the results.

All three freshwater mussel species showed little impact from microplastics. For zebra mussels in particular, microplastic toxicity only affected their ability to filter algae for food. The researchers believe this happens as a result of their ability to filter out microplastic particles before ingesting them. Given the harsher impacts of microplastics on other animals, the team may study how the filtering is so effective in comparison to other shellfish, for instance.

Germ-free mice show how eating common oils affects our microbiomes

New research adds to our knowledge about how the oils we eat affect our bodies

Fat, oil, and lard. The purported nutritional value of each has changed over the past decade, and while health experts now assert that not all fat is bad for you, it can be challenging for the everyday person to figure out which one to eat.

Oil from soybeans is the most widely consumed oil in America. However, its effects on the gut microbiome are poorly understood. Studying this oil and how it interacts with gut bacteria can help us to understand the its impacts on our health.

A study published recently in the Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry looked at how soybean oil interacts with mouse microbiomes, as a model for how it affects human microbiomes. Soybean oil is rich in health-promoting omega-6 fatty acids, which are broken down into smaller molecules called sphingolipids and ceramides. In healthy mice, increased levels of ceramides found in the liver have been shown to result in insulin resistance while those found in the blood are associated with cardiovascular disease.

To model human diets, standard lab mice and mice devoid of all microorganisms (germ-free mice) were fed either low fat diets or diets supplemented with soybean oil for 10 weeks. The researchers measured fatty acid and sphingolipid levels in their blood and livers, and analyzed microbial DNA from their feces to determine the amount of gut bacteria present.

One group of germ-free mice was found to be contaminated with bacteria at low levels due to difficulties in sterilizing the diet. This group led the researchers to find that large amounts of gut bacteria present may increase the amount of ceramides in the liver regardless of how little or excess fat is consumed. High soybean oil levels made the mice gain fat, but those with colonized microbiomes were able to accumulate more fat than the germ-free mice. Therefore, they concluded that sphingolipids in the liver are more affected by our gut microbiomes than the amount of fat in our diets.

This study suggests that soybean oil consumption in Western diets should be moderated with future interest in finding alternative sources of omega-6 fatty acids.

How binary stars' planets are born

A new mathematical simulation shows how gas and dust could swirl into planets in dual-star systems

ESO/L. Calçada/Nick Risinger (skysurvey.org)

Want to make a new planet? All you need is a newborn star and a metric boatload of gas and dust particles. As they orbit the young star, these tiny bits of ice and dust collide, eventually growing up into full-blown planets.

Seems simple enough. But what about making a planet with two suns? Stars are generally much bigger than planets, and throwing a second one into the mix — as in a binary system — speeds up how fast the pre-planet space dust swirls around thanks to increased gravitational forces. At those speeds, collisions mean destruction and it’s hard to build a planet. But scientists have detected exoplanets orbiting around binary star systems. So how did they get there?

A new mathematical model solves this mystery by simulating the planet formation process in a specific type of binary star system, where the smaller star orbits around the larger star about once a century. The researchers found that, as long as the bits of dust and ice swirl around the main star in a roughly circular orbit, any drag effects from stellar gas become very large in certain parts of the disc. This drag slows down the dust particles to more reasonable, less explosion-y speeds so that they can actually stick together instead of destroying each other. The leading particles in a group are slowed more than the ones behind it, allowing the trailing particles to catch up and join the expanding clump. It's like a cycling road race. Cyclists tend to race in packs because wind drag is reduced behind a teammate. Once larger boulders about 10 kilometer in diameter are formed, they can survive high-speed collisions and are able to grow normally up to planet sizes.

While this particular kind of binary star system is now better understood, the next mystery for the new model to tackle is the formation of "Tatooine"-style planets, which orbit both stars in a binary system instead of just one. NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope has already found some of these deep in space, but we still don’t quite understand how they’re made.

Can slime molds remember?

Unique signals may propagate through the slime mold's tendrils when they reach food

Seiya Ishibashi / Wikimedia

Slime mold, Physarum polycephalum, is famous for its seeming intelligence in completing mazes and recreating the map of railways. Sometimes called The Blob, this unicellular network of tubes grows in intricate designs that slowly pulsate and crawl across rotting logs. They eat dead plants and will reconfigure their structures to approach food — enlarging their tendrils toward snacks. Researchers have described this behavior, where a slime mold repeatedly positions near a food source, to reflect formed memory. A pair of scientists, Mirna Kramar and Karen Alim, wanted to understand how a network of tubes can remember. Kramar and Alim's results appeared in PNAS in March.

Previous explanations, such as mechanisms involving epigenetics and altering gene expression, would require at least 30 minutes to establish a non-neuronal memory — too long to fit slime mold learning observations. The researchers made mathematical models to explain how slime mold changes its shape, and they found that food triggers a progressive change in tendril diameter that is slower than the speed of pressure propagation but faster than speed of diffusion. Therefore, perhaps a signal is being transported in the fluids within the tendrils. This signal was proposed to be released when contacting food, increasing tendril diameter while simultaneously shrinking the distant tendrils (because the total fluid volume within all of the tendrils remains constant).

Although Kramar and Alim did not directly test the nature of this signal, they proposed that it is a chemical that softens the tendril structure, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). ATP levels have been measured to be double in slime molds at their migration front than the trailing back. Softening tube walls helps the slime mold grow or spread when migrating.

Researchers use “memory” more broadly than in colloquial terms, but are slime molds really exhibiting associative memory, or are they just reacting? The mentioned study suggests that slime mold exhibits encoded memory because their shape persists longer than transient reactions. Its corresponding commentary gently initiates a philosophical discussion for distinguishing memory from reactions.

Without synaptic "nibbling," mice develop behavioral problems

Mice without microglia grow up with an excess of inhibitory neurons

Via Wikimedia

Synapses are the connection points between neurons where information is exchanged through chemical signals. As infants, we have an abundance of these connections, but when we transition into adulthood, the number of synapses in our brains decrease substantially. During this process, called synaptic pruning, unnecessary synapses are eliminated in order to strengthen the most important ones. By reducing synapses, the brain refines the circuits that allow us to learn, remember, and function properly throughout our lives.

One of the key players involved in pruning are microglia, the immune cells of the brain. Microglia “nibble” at pieces of synapses, which allows new connections to form as the brain is remodeling during development. Researchers have been investigating how microglia can target specific types of synapses and why microglia nibble some synapses in favor of others.

A group of scientists recently discovered a subset of microglia that make direct contact with inhibitory synapses. These synapses can be thought of as a brake pedal, and when they release the neurotransmitter GABA, they subdue activity of the cell receiving the signal. Interestingly, microglia make most of these contacts with GABA synapses early in life, during the prime time for synaptic pruning.

The researchers used mice to find out the role of microglia in the development of these connections. They treated newborn mice with a compound that diminishes microglia during the critical window when those microglia would typically be most active in pruning. When the microglia-deficient mice grew up, their brains contained more inhibitory synapses compared to mice that grew up with intact microglia. Genetically altered mice that lacked microglia with GABA receptors were also impacted behaviorally, displaying more hyperactive tendencies.

Microglia are crucial for remodeling synapses in the brain early in life. When microglia functioning is disrupted, it can affect synaptic pruning and lead to behavioral disorders including schizophrenia and ADHD. By characterizing different subtypes of microglia and how they interact with neurons, scientists are revealing how synapses become mature and how these processes can go awry.

Tapering off opioids is treacherous for mental health

A large-scale study shows how the opioid epidemic has created downstream negative health outcomes

Via Wikimedia

The causes of the US opioid epidemic are complex, but excessive prescription of opioid painkillers played a significant role. As a result, health authorities now recommend that doctors gradually reduce or discontinue prescribing opioid painkillers to their patients with chronic pain, a practice referred to as opioid tapering.

But authorities warn that opioid tapering can come with risks. In a new large-scale study, researchers demonstrate the potential dangers associated with opioid tapering.

The results were recently published in the Journal of the American Medical Association by a team of researchers at the University of California, Davis. To evaluate the potential harm of tapering opioid prescriptions, the researchers looked at the health data of 113, 618 people who were prescribed stable, high-dose opioid therapy for at least a one year period of time from 2008 to 2019. Next, they compared the health outcomes of people whose opioid therapy was tapered to the health outcomes of people before opioid tapering or whose opioid therapy was not tapered. They found that opioid tapering is associated with an elevated risk of both drug overdose and mental health crises, specifically depression, anxiety, and suicide attempts.

The researchers caution that interpretation of their findings is limited by the study’s observational design. Nonetheless, the results raise questions about the risks of opioid tapering, highlighting the importance of taking steps to minimize those risks, such as careful planning, monitoring, and coordination between patients and doctors.

When a person "detransitions," pressure and threats — not regret — are most often the cause

In a study published in LGBT Health, researchers analyzed survey data of 27,715 trans and gender diverse US adults

Trans and gender-nonconforming people may express themselves in gender-affirming ways, such as choosing clothing, changing their names or pronouns, beginning hormone replacement therapy, and undergoing surgery. “Detransitioning” — reverting to representing oneself as one’s sex assigned at birth — is often incorrectly conflated with regret by the media.

In a study published in LGBT Health, researchers of psychiatry and health policy examined results from the US Transgender Survey, which includes responses from 27,715 transgender and gender diverse adults, and found that very few people detransitioned due to internal regrets. Of 2,242 survey respondents who detransitioned, 82.5 percent did so because of external factors, such as pressure from family, threats of violence, or losing employment or education opportunities. Only 2.4 percent of respondents who reported detransitioning attributed it to doubt about their gender identity.

This result characterizes a relatable, human experience: wanting to be safe and supported by one’s family and community. People who choose to detransition may remain part of the trans community and may later seek gender-affirming care.

Precise CRISPR gene editing can correct the mutation that causes cystic fibrosis in mini-intestines

Prime editing, which edits DNA directly without cutting, restored healthy function in an organoid model of an intestine

Via Wikimedia

For the first time, a type of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, called prime editing, has been performed in “mini-organs” to correct the mutation causing cystic fibrosis.

Cystic fibrosis is thought to affect more than 70,000 people worldwide. It is a genetic disease caused by a mutation in a single gene, called the CFTR gene, which result in a dysfunctional CFTR protein. This dysfunctional protein aspect is what causes the main symptom of cystic fibrosis; a sticky mucus buildup in the respiratory tract and lungs.

Published in Life Science Alliance, researchers from the Hubrecht Institute, in collaboration with UMC Utrecht and Oncode Institute, demonstrated that they were able to correct a mutation in CFTR that causes cystic fibrosis by performing genome editing in a mini-organ called an organoid. The organoids, mini intestines, had been grown from stem cells originally collected from patients with cystic fibrosis.

Prime editing is different than traditional CRISPR genome editing. Instead of acting as a pair of scissors, prime editing uses a modified Cas9 protein to make a direct change to the DNA sequence. In doing so, the researchers are able to change the underlying DNA sequence without cutting the DNA. This also reduces the risk of Cas9 cutting randomly elsewhere in the genome.

To test if the prime editing was successful, the researchers, led by Hans Clever, added a treatment called forskolin to the organoids. In healthy organoids, addition of forskolin causes the mini-intestines to swell up due to movement of fluids into the center. The researchers found that this happened in some of the prime edited organoids as well, suggesting that the mutation had been corrected. Organoids that carried a CFTR gene with a mutation however, did not respond to forskolin treatment.

Prime editing efficiency is variable between organoids and cell types, an important consideration in the developments towards gene therapy for cystic fibrosis and other diseases. Moreover, significant research effort should be invested into ensuring that prime editing techniques do not cause any unintended off-target effects. Despite this, these proof-of-principle research findings provide a step forward for the understanding and future developments of gene therapy for cystic fibrosis treatment.

Researchers find biomarkers for heart disease in young adults

The proteomic analysis detected differences in oxidative stress markers

Unsplash

Cardiovascular diseases, or CVD, are the leading cause of mortality in the United States. As such, early detection of the risk factors for CVD allows for preventive measures to be put in place.

Many of the current risk prediction algorithms place the most emphasis on age as a contributor in developing CVD. Consequently, CVD risks for many younger adults are often underestimated. A recent study from vascular physiopathologists in Spain searched for a new method to estimate CVD risk for this population using a technique called proteomics, by quantifying risk of CVD in young adults based on the proteins found in their plasma. They were particularly interested in oxidative stress markers, because oxidative stress is associated with the development of CVD. Oxidative stress occurs when you have more free radicals than antioxidants in your body, which damages your cells.

The study placed younger adults into three groups: healthy participants, participants with risk factors for CVD, and those who had already experienced a cardiovascular event. Among the proteins found in the participants' plasma samples, the team identified more irreversible oxidation of certain amino acids in those who had experienced a cardiovascular event, compared to healthy adults.

The results indicate that oxidation is progressive with the development of CVD. Additionally, there were increases in the antioxidant response for both the adults with CVD risk factors and patients who had already experienced a cardiovascular event. This antioxidant boost is assumed to be a response to the increased oxidative stress seen with CVD.

Ultimately, these results revealed exciting findings that both markers of oxidative stress and the antioxidant response are altered in those at risk for CVD. Thus, these biomarkers may be clinically useful in developing better tests to quantify the risk of CVD in young adults.

Move over, mice: sheep have the superior brains for neuroscience research

Sheep brains more closely resemble human brains than do mouse brains

Sam Carter via Unsplash

Animals are crucial for neuroscience research. Many important discoveries have been made by studying the brains and cells of different animals. For example, we learned how the brain encodes information from the eye through experiments on cats, and we learned how information is relayed by neurons from the squid giant axon. Nowadays the majority of such research is done on mice and rats. These rodents are easy to train and don’t take up a lot of space, making them perfect for neuroscience research.

However, rodents also have a big disadvantage. Although they are mammals, their brains do not look much like human brains. As a consequence, not all research that is done on rodents is translatable, meaning that findings from rodents do not necessarily apply to humans. This is especially a problem for research on diseases and their treatments: treatments that work in mice, may not work in humans. Many alternative animals have been proposed over the years to address this problem, but each has their own challenges.

In a recent preprint, researchers proposed a new alternative to rodents for neuroscience research: sheep. Sheep have brains that look similar to human brains. In addition, sheep are smarter than you might think. The scientists were able to teach them a behavioral task (the sheep had to choose between two different stimuli in order to receive a food pellet) and for the first time recorded the activity from their brains while the animals were performing it. They showed that the brain showed the same patterns of activity as rodents and humans, both during the task and while the animals were moving around.

Although this study was the first to perform recordings from a sheep’s brain while it was actively walking around, it follows earlier studies where sheep were already used for the study of various diseases, such as Huntington’s disease. Together this makes sheep a promising alternative to rodents for studying treatments for diseases that affect the brain. Hopefully, studying these woolly animals will lead to many new discoveries in neuroscience.

Earth's oxygen is projected to run out in a billion years

As the Sun ages, Earth's processes will change

Photo by Jonathan Borba on Unsplash

Our Sun is middle-aged, with about five billion years left in its lifespan. However, it’s expected to go through some changes as it gets older, as we all do — and these changes will affect our planet. New research published in Nature Geoscience shows that Earth’s oxygen will only stick around for another billion years.

One of the Sun's age-related changes is getting brighter as it gets older. When a star runs out of hydrogen fuel in its core, the core has to get hotter in order to fuse the next element, helium. As the core gets hotter, the outer layers expand, and the star gets brighter. This extra energy hitting Earth will eventually cause our planet to warm up and slowly lose its oceans and its oxygen.

The exact timing of when we lose our oxygen depends on more complicated factors — particularly our planet’s carbonate-silicate cycle, which releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere from volcanoes. As the mantle cools and this cycle slows, less carbon dioxide will be available for the plants that produce oxygen, leading to a rapid loss of oxygen in the atmosphere. The researchers’ model took into account all these factors — our biosphere, the Sun’s changes, our planet’s changes, and more — to come up with their estimate of about a billion years.

Interestingly, this means that planets like Earth only have oxygen for a fraction of their lifetimes. When we try to find habitable worlds, this will be important to keep in mind.

Your saliva affects the way you spread pathogens

Our saliva can vary depending on our physiological state, making us more or less likely to pass on bugs to others

Pereru via Wikimedia Common

We've all been in a crowded place and seen someone sneezing or coughing nearby. You do your best to get away from them, but somehow they always end up right there beside you. The COVID-19 pandemic has increased our collective use of masks and other protective measures that have reduced the transmission of many viruses beyond coronaviruses, including influenza.

Researchers are now finding that there are specific qualities of saliva that might change how easy it is to catch certain pathogens. You may think that everyone's saliva is the same, but our physiological state changes our saliva! If you're stressed or dehydrated, for example, your saliva makeup is different than it would be if you weren't. Saliva thickness also differs between genders: women tend to have thinner saliva, and less of it than men.

University of Florida researchers have found that what compounds are in your saliva, your salivary flow rate (how much saliva you produce), thickness, and other features make the saliva able to travel further when you cough or sneeze. This comes into play when we talk about respiratory viruses like the one that causes COVID-19, which are transmitted by respiratory droplets.

With these suggestions, it may be possible to alter your saliva to decrease your ability to pass potentially deadly bugs to others. Could simply keeping yourself hydrated and being less stressed reduce virus and bacterial transmission? University of Florida researchers say very possibly!

Alzheimer's drugs targeting amlyoid plaque may be doomed to fail

In a study of the cause of Alzheimer's, cognitive decline tracked something other than high levels of amyloid plaques

National Institute on Aging, NIH

In June, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first drug designed to slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. The drug, called aducanumab, clears amyloid plaques — clumps of brain proteins that are characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease. Proponents of the drug say that amyloid plaques are toxic, and that they lead to brain inflammation and the loss of brain cells, causing cognitive impairment.

But critics say there is scant evidence that the drug actually helps people with Alzheimer's, and not all scientists agree that amyloid plaques cause the disease, though there is a correlation. In fact, some people with amyloid plaques do not show cognitive decline.

In new study, University of Cincinnati researchers sought to understand this apparent paradox. Their idea is maybe the cause of Alzheimer’s is not an accumulation of these protein clumps, but rather a decrease in their precursor: soluble un-clumped amyloid proteins in the brain. Soluble amyloid proteins have a number of important jobs in brain function, including brain development and protecting brain cells from premature death.

To test this idea, the researchers looked at soluble amyloid protein levels in people with varying stages of cognitive decline. They found that healthy individuals with amyloid plaques in their brains still had high levels of the soluble amyloid protein. Dementia was much more related to low soluble protein levels than it was to high levels of amyloid plaques. These results add to the evidence that plaques may not be the direct cause of Alzheimer’s, and they calls into question the FDA’s decision to approve aducanumab.

New machine learning approach can identify your circadian rhythm from a blood sample

Doctors do not currently monitor a person's circadian rhythms because there is not an efficient way to measure them

Sharon Mccutcheon via Unsplash

Many of the body’s physiological activities, including hunger, wakefulness, and metabolism, run on 24 hour cycles called circadian rhythms. These cycles are primarily controlled by the release of chemical messengers into the bloodstream from the brain and have been linked to cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative disorders, and weight-gain.

Measuring circadian rhythms could significantly improve medical care. Doctors could better prevent and treat illness by more accurately assessing individual risk of disease and recommending times to eat, take medication, and rest. Circadian rhythms are not used as a clinical indicator at present because there is not an efficient way to measure them. Based on the results of a new study, however, that could change soon.

The results were recently reported in the Journal of Biological Rhythms by a team of researchers at the University of Colorado at Boulder. The researchers sought to develop a circadian rhythm test that is more efficient than the standard dim-light melatonin assessment, which requires hourly collection of blood over the course of an entire day to measure the amount of a sleep-inducing molecule in the body called melatonin. The test is accurate, but it is impractical for clinical use.

To develop an efficient circadian rhythm test, the researchers invited 16 participants into their sleep lab. Over the next two weeks, the researchers took regular blood samples and analyzed them to measure the levels of melatonin and approximately 4,000 metabolites, molecules that are produced by biochemical reactions in the body. Then, they used machine learning to determine which metabolites are associated with different phases of the circadian rhythm. When the analysis was complete, the researchers could measure circadian rhythms by testing a single blood sample for 65 metabolites with similar results to the dim-light melatonin assessment.

The new test does have some limitations; it worked best for people who had adequate sleep and whose food intake was controlled, which limits its practical application, and it would be more efficient if fewer metabolites had to be analyzed. Nonetheless, the study results are exciting and suggest an efficient circadian rhythm test may be available soon.

Tiny radio tags reveal the lives of Neotropical stingless bees

These bees are small, but the tags are smaller

Photo by Denise Johnson on Unsplash

Scientists have struggled for years with ways to understand bee movement and foraging behavior. Following bees around from flower to flower is tedious, and netting bees to identify species visiting different types of flowers only tells us so much about their behavior over a large area. Where bees are foraging, and what they're eating, will give insight into their health and survival in the face of changes to their habitat and climate.

In a recent paper from Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, researchers attached radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags to the backs of a Neotropical stingless bee, Melipona fasciculata, to monitor their behavior. Similar to the little tags attached to some clothing that beep loudly when you bring them past the doors of a store, RFID tags can be used to track movement using microcomputers. Researchers found that 64.1 percent of tagged M. fasciculata individuals would drift between nesting boxes to other colonies of bees. Their peak activity occurred at 9 am, and pollen foragers lived longer than nectar foragers.

This amazing research establishes a new system for understanding bees using RFID tag technology, and increases our understanding of Neotropical stingless bees.

How “evolutionary medicine” helps create drugs that prevent antibiotic resistance

How do you stop a bug from becoming a superbug? Beat it at Darwin’s game

Maksym Kozlenko, CC BY-SA 4.0 / Wikimedia Commons

Though it sounds like a plot device from a dystopian novel, the term “superbug” describes very real disease-causing microbes that have overcome the drugs normally used against them. These bugs kill over 35,000 people every year in the US alone, and the WHO considers them one of the biggest threats to global health and security.

In the arms race against microbes, scientists have begun fighting back by targeting the bugs’ most powerful weapon: the capacity to evolve. Antibiotics jam up essential proteins in bacteria, often by binding to crucial areas called “active sites.” The lock-and-key fit of these drugs makes them work with deadly precision right up until the bacteria change their locks. The liberal use of antibiotics creates dramatic evolutionary pressure, breeding superbugs with mutations in these active sites that prevent the drugs from binding.

A paper published in eLife in July describes an effort to shut down evolutionary routes to antibiotic resistance by tailoring a drug’s chemistry to preempt mutations. The idea was that, rather than waiting for evolution to render current drugs useless and require a return to the drawing board, scientists might design them to bind to essential areas within the site that tend not to mutate, prolonging their lifespan.

Using computational chemistry, scientists tested 1.8 million chemicals for their ability to bind to a commonly targeted bacterial protein, both with and without real-life resistance mutations. They then brought the best candidates into the lab and put them to the test, pushing bacteria to evolve in response to them. In a success, the group found that one chemical dramatically weakened and delayed the bacteria’s evolution towards resistance. While the study’s specific chemical is not quite a silver bullet, its proof of principle bodes well for the use of this “evolutionary medicine” tactic in the design of future antimicrobials as well as drugs for other diseases that acquire resistance, like cancer.

What engineers can learn about infrastructure from predatory army ants

Ants can teach us how to design strong networks resilient to individual failures

Alex Wild via Wikimedia Commons

Engineers are grappling with a problem army ants solved ages ago: how can we design massive, coordinated networks that don’t topple when one individual fails? While it seems like big groups need one, centralized commander calling the shots, nature demonstrates otherwise. Simple rules followed by individuals, independently, produce incredible group-level behaviors. An April 2021 study published in PNAS turned to Eciton burchellii, predatory Central American army ants, to learn how they become greater than the sum of their parts.

E. burchellii hunt in massive swarms, hundreds of thousands of ants strong. When faced with slippery slopes, they team up to form living structures called “scaffolds,” making footholds for the ants coming up behind them.

To model how ant colonies shape their behavior to the environment, researchers traveled to Barro Colorado Island, Panama. They built a moveable platform that could be tilted from 20 degrees (mostly flat) to 90 degrees (completely vertical), set the platform along the ants’ path, and watched. The steeper the slope, the denser the scaffold. Why? Selfish behavior.

If an ant slips as they're climbing a precarious surface, they will dig in, gripping the underlying surface. Their body acts as a foothold, making the climb less slippery for the rest of the swarm. As more ants slip and catch themselves, their bodies add to the scaffold. As the surface becomes easier to grip, fewer ants slip, and scaffold construction winds down to a halt. This is an example of proportional control, where a system responds in proportion to the amount of error it detects. The rate at which bodies are scaffolded (the system’s response) decreases as fewer ants slip (the error it detects).

Ants and their remarkable collective behaviors can inspire us to improve our own infrastructure. Mechanisms inspired by E. burchellii scaffold-building, which robustly and quickly respond to change, could be used to design self-healing fabrics, build better traffic control systems, and more.

Top-ranking baboons age the fastest. Is it worth it?

New research looks at the epigenetic effects of social status in baboons

capri23auto / Pexels

Maybe you found a grey hair on your head in your twenties. Might this lead you to wonder if maybe all your stress is making you age faster? It might, if you’re a high-achieving male baboon.

Our DNA collects different chemical modifications know as epigenetic changes. Some of these are age-related and make up our “epigenetic age.” Someone’s age in years and epigenetic age don’t always agree, and in humans faster epigenetic aging has been associated with increased disease risk and shorter lifespan. However, we’re still learning what influences epigenetic age in humans and other animals.

A recent study published in eLife shows that social status is the best predictor of epigenetic age in male baboons. This faster aging isn’t true for female baboons, who inherit their ranks from their mothers. Therefore, the researchers posit it’s not the rank of male baboons that accelerates their aging. Instead, it’s the process of climbing the social ladder. So why would social climbing among baboons be associated with faster aging?

For male baboons, rising in rank means fighting for it, and their rank can change in their adult life. Not only does high status increase epigenetic age, but dropping in status can reverse accelerated aging as well. This “live fast, die young” way of life may still be worth it, from an evolutionary perspective. Despite the cost, high-ranking males are still more likely to reproduce. Social pressures among humans don’t align with those of baboons. Nevertheless, learning how other primates age and why can help us better understand the factors that contribute to aging in humans.

Access to free school lunch creates health benefits for a lifetime

A study of India's Midday Meal program shows clear nutritional benefits that are even passed on to the next generation

MD Duran

School lunch programs are widely known to improve children’s health and education, but their benefits may extend even further than once thought. According to a recent study from the International Food Policy Research Institute, India’s national school meal program may provide intergenerational health benefits extending to participants’ own children.

India’s Midday Meal is the largest school meal program in the world, feeding around 100 million school children each year. The success of this program led researchers to wonder whether meal recipients grew up to have healthier children of their own.

The team found that women who grew up with school meals had young children (ages 0 to 5) who were taller for their age than the children of women who did not receive school meals. There were also fewer children with very short heights for their age, a common sign of malnutrition, among women who had experienced greater access to school meals. These differences were largest at low socioeconomic statuses, suggesting that school meals may be most beneficial for children with few resources at home.

They also found that school meals were associated with improved education and healthcare use by women, which may partially explain the nutritional gains in their children. This study highlights how a single free meal a day can have cascading effects across lifetimes.

What does a spider eat? Look at the DNA in their guts

DNA sequencing found wandering spiders eat at least 96 types of prey, including snakes and lizards

Despite not being the favorite animals of many people, spiders are very important land predators that shape the structure of ecological communities and control the populations of their prey species. Some spider species, like the South American “banana spiders” or “wandering spiders” (genus Phoneutria), are also of medical concern due to their potent venom.

The diet of spiders is mainly inferred by observations in the field and laboratory, which is potentially biased and probably underestimates the number of species ingested. Spiders also pre-digest their prey externally before ingesting, increasing the difficulty in identifying their prey.

With more advanced molecular technique and ever-growing DNA databases, it is now possible to perform molecular gut content, that is, sequence the DNA present in the gut of the spiders and match them to existing sequences in databases allowing a more precise identification of species. This methodology is called DNA meta-barcoding.

Researchers from the Universidad del Tolima and Universidad de Ibagué in Colombia were the first to use DNA metabarcoding to analyze the diet of a wandering spider, the Phoneutria boliviensis (disclosure: I, the author, worked on this project). We sequenced the guts of 57 spiders and identified 96 species of prey belonging to 10 orders, mainly flies, beetles, butterflies, moths, grasshoppers, locusts, and crickets. We also found the DNA of a species of lizard and snake among the prey species eaten by females.

In this study, females had a smaller number of preys identified compared to males, even though the opposite was expected since females of this species are generally larger. However, these results indicate that the two sexes have different predatory strategies. The 57 spiders analyzed belong to three different populations in Colombia, and the prey composition of each population also differed, indicating that the three localities have small differences in prey availability.

This study confirms that wandering spiders feed on a wider variety of species than previously reported, further validating their generalist nature and flexible diet.

Illegal shark fishing study shows widespread catch of threatened Galapagos species

The Fu Yuan Yu Leng 999's catch of a dozen different species of sharks is a sign that endangered species need better protection

Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 4.0)

Many fish stocks are expected to be depleted during the coming years due to overexploitation and illegal fishing. Shark fishing driven by the million-dollar fin trade have pushed some species of shark into a heightened risk of disappearing. To counteract overfishing and preserve biodiversity, some governments have created marine protected areas (MPA) where the species can thrive without human pressure.

The Galapagos Marine Reserve, an MPA in the east Pacific, harbors and protects 36 species of sharks. This makes it a popular destination for divers and researchers attracted to its biodiversity. Nevertheless, the same biological richness also attracts illegal fisheries that trespasses the borders of the reserve, exploiting the difficulty of open sea monitoring.

In August 2017, the Fu Yuan Yu Leng 999, a Chinese vessel was captured inside the GMR with 572 tons of fish including hundreds of sharks. The boat’s crew were sentenced from 1-3 years imprisonment and fined $6 million for the illegal possession and transport of protected species. The silver lining was that the seized cargo gave the opportunity for a group of researchers to study it, using morphological and molecular barcoding.

They found that from the 12 species of shark identified, 11 were present in the GMR from which 9 species are considered at risk. The cargo was composed of species of different sizes including a whale shark, to reef species that would suggest illegal trade with coastal fisheries. Several immature and unborn sharks were found on the boat; for one species immature individuals made up 86 percent of the total sample analyzed. Moreover, the researchers used advanced molecular techniques to attempt to identify the geographic origins of the cargo. Unfortunately they were unsuccessful due to the limited availability of molecular samples of the region stored in the international genetics database.

This case exposes the magnitude of the threat posed by fishing industries and illegal trade in marine reserves on already vulnerable shark populations. Additionally, it highlights the importance of satellite technologies in the monitoring of fishing activities, that in the case of the Fu Yuan, provided the evidence necessary for the successful prosecution of the culprits.

Researchers might be using your Facebook data in their papers

A recent study asked people what they thought about academics using their social media data

Photo by Glen Carrie on Unsplash

After the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica data scandal following the 2016 United States presidential election, public conversation has revolved around appropriate uses of social media data across domains, including academic research.

The collection of user-generated data from social media can blur the line of what constitutes human subjects research. While this data is generally considered beyond the purview of institutional review boards, users are often disconcerted by the lax approach to their data. A recent study surveyed active US Facebook users about their perspective on social media data use in academic research.

Results indicate that the purpose of data collection mattered to people: while health science-focused research was viewed as an appropriate use of social media data, gender studies, computer science, and psychology research was not. This may indicate that fields seen as “more political” could experience backlash regarding data collection. Post content and context were also relevant, with participants rating public comments about food or science as more appropriate for collection than posts about more personal topics made in groups or sent via private message. Users also indicated that research which sought their consent was less concerning, and that research used for service improvements rather than knowledge generation was more appropriate.

These findings suggest that the discipline and purpose of the research, the kind of data collected, and the subjects’ awareness of the research affected how users assessed the appropriateness of the data collection. Researchers should be cognizant of these preferences when conducting research to help ease subject anxiety, promote public scholarship, and use context-informed methods in their studies.

Animals and their DNA move through the environment in different ways

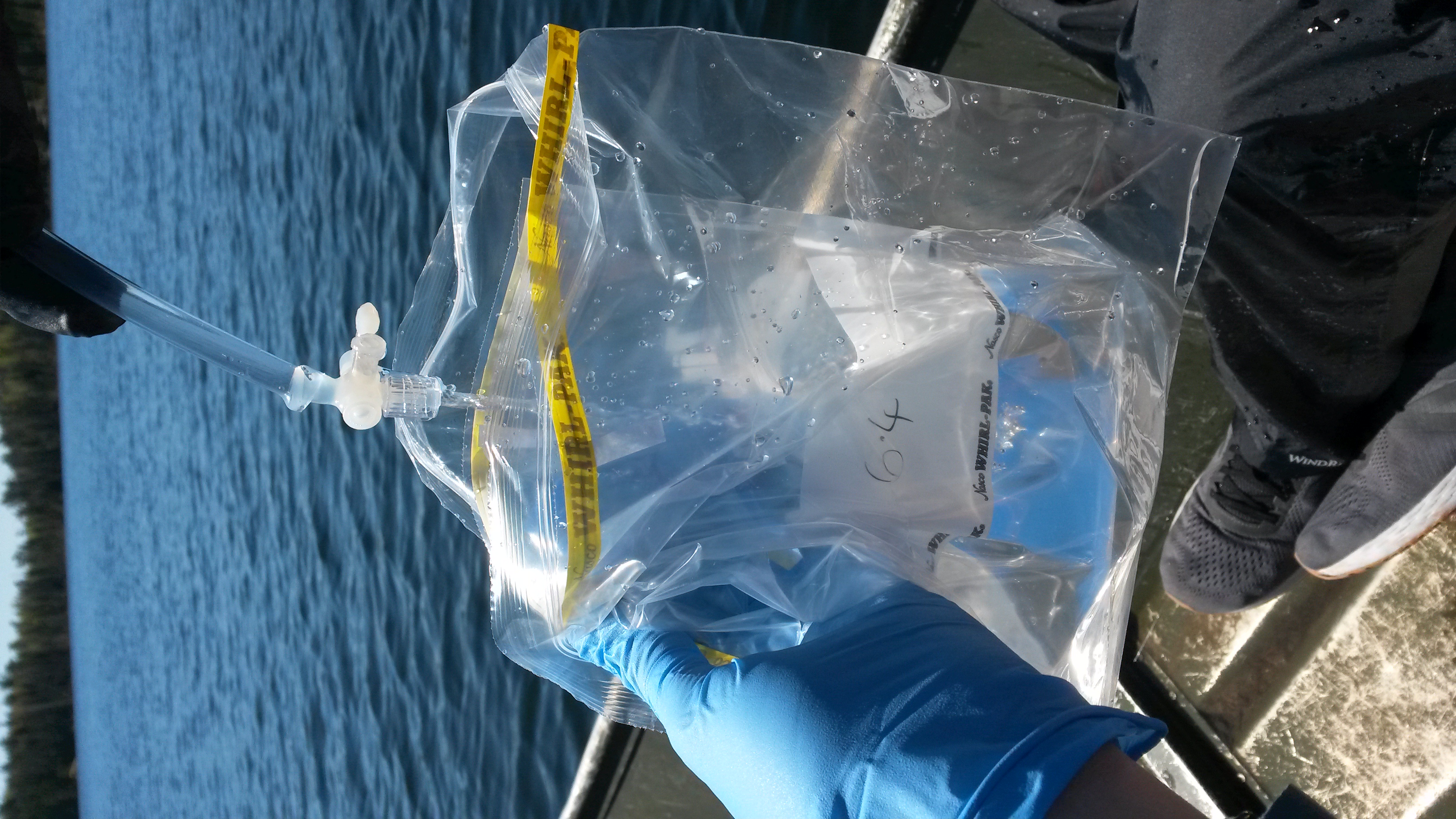

Sampling a lake at different times of year and at different depths found fish DNA distributes in unexpected ways

Environmental DNA (or eDNA) is all the rage in ecology. Animals create and shake off DNA every day, leaving tracks as to where they’ve been. The DNA that has been shed into the environment can be sampled and tested later.

While the potential to test for a species without having to see or capture it is exciting, we need to be sure of its accuracy. Can biotic and abiotic processes in the environment influence how eDNA is distributed in an ecosystem?

A recent study at IISD Experimental Lakes Area, a remote lake research area in Ontario, suggests that the distribution of eDNA in lakes can be affected by both summer stratification and fall turnover. Researchers tracked lake trout (Salvelinus namaycush) DNA and then compared those data to where the lake trout actually were, verified using acoustic telemetry.

The study revealed that during summer months, when the lake is stratified and the trout spend their time in the lake's deep waters, they could mostly only be detected using eDNA at the deepest layers of the lakes. In fact, lake trout eDNA was not detected at all in the surface water despite the presence of abundant lake trout populations in the lake.

Sampling from a lake

Joanne Littlefair

By contrast, during fall lake turnover when lake trout spend much of their time near the surface, their eDNA was found pretty much everywhere throughout the water column, likely being mixed in as the lake water turned over.

Many eDNA sampling programs only sample surface water. The study found that if only surface water were sampled in these lakes while stratified, lake trout — the abundant top predator in the lakes — would not have been detected. It also revealed that sampling during a period of lake mixing (fall through spring) or sampling the entire profile of the lake in summer will increase the probability of detecting all species present.

Measuring eDNA remains a reliable way to monitor animals in their environments. The study demonstrates the need to design eDNA sampling methods accordingly to take lake physics into account and be aware of those physical processes’ impacts on the results.

Drinking way, way too much coffee might shrink your brain

Up to five cups of coffee per day seems to be fine. Six or more? Your brain is going to feel it

Coffee ranks as one of the most popular drinks on the planet after water, alcoholic beverages, and fruit and vegetable juices. There are many reasons that people drink coffee, but most people drink the brew to improve their brain function.

In fact, research shows that moderate coffee consumption (3–5 cups per day) can enhance concentration and alertness and improve health outcomes by decreasing risk of chronic disease. In a new large-scale study, however, researchers found that drinking over six cups per day may negatively impact brain function.

The results were recently published in the journal Nutritional Neuroscience by a team of researchers at the University of South Australia. To look at the association between coffee consumption and brain health, the researchers conducted a prospective analysis of data collected by the UK Biobank, which has amassed detailed health information on over half a million participants in the UK.

The scientists analyzed the data associated with 398,646 UK Biobank participants. They compared self-reported consumption of caffeinated coffee and measures of brain volume acquired via MRI and found an inverse association between coffee consumption and total brain volume (brain volume isn't associated with intelligence, though brains tend to shrink as we age). In addition, their analysis revealed that drinking more than six cups of coffee per day is associated with a 53 percent greater probability of dementia compared to drinking 1–2 cups of coffee per day.

The results build on previous research showing that drinking large amounts of coffee is associated with worsened health outcomes such as anxiety and insomnia. Luckily, because most coffee drinkers drink about three cups of coffee per day, odds are you can continue to enjoy your morning brew without worry.