Matteo Farinella

Four times that Margaret Mead challenged societal norms

How the most influential anthropologist in history broadened views on sexuality and cultural influences

Margaret Mead is considered one of the most influential anthropologists in history. Her nearly 60-year research career, which began in the late 1920s and stretched until her death in 1978, pushed boundaries. She laid the groundwork for the sexual revolution in the 1960s and many scholars see her as the anthropologist who popularized the discipline.

Her most famous body of work is her study of cultures in the South Pacific and Bali. Her first book, Coming of Age in Samoa, kicked off a career that included 14 research trips and produced over 40 books. She helped inspire anthropological feminism, the sexual revolution, and other countercultural trends, none without controversy.

Matteo Farinella

Let’s look at four times Margaret Mead was ahead of her time, pushing the boundaries of societal norms.

(1) Broadening views on sexuality

Mead’s early research on child rearing, personality, and culture resulted in her first book Coming of Age in Samoa: A Psychological Study of Primitive Youth for Western Civilization, in 1928. She wanted to study a culture that was not well understood, one that was radically different from Western culture, with the goal of learning whether the difficult adjustments from childhood to adulthood were a symptom of civilization or the nature of adolescence. She spent between six and nine months living with a village of 600 people on the Samoan island of Ta’u. She learned some Samoan and interviewed 68 women between nine and 20 years old while also observing daily life, education, and social structures.

Compared to what she saw in the West, she noticed that the loosening of social constraints on sexuality could lead to more pleasure and less suffering, noting that more sexual freedom and familiarity makes sex less charged with conflict that she saw in the west. In Coming of Age in Samoa she writes, "romantic love as it occurs in our civilization inextricably bound up with ideas of monogamy, exclusiveness, jealousy and undeviating fidelity does not occur in Samoa."

Margaret Mead visiting with a Samoan family in her later years

Tomste1808 on Wikimedia Commons

Many argue that Mead was motivated by her own political agenda as she herself was a proponent of broadening sexual conventions within the traditional Western religious life (she was married three times to men, but her longest relationship was with a woman).

Her biggest critic was the anthropologist Derek Freeman. Freeman devoted his life to discrediting Mead, spending years in Samoa and publishing several books and articles in a controversy that lasted three decades.

However, Freeman’s claims were later shown to be unsubstantiated. For example, Freeman asserts that Mead was misled by Fofoa and Fa'apaua'a, two Samoan women she interviewed. During Freeman's own visit to Samoa he spoke with Fa'apua'a, one of the same women that Mead spoke with six decades prior, and heard quite a different account. However, the interview was arranged by Fofoa's son, a Samoan Christian who asked her to correct the lies and insults about Samoan sexuality in Mead's book. Yet, Mead's field notes did not have any information on sex from the two women. She couldn't have been misled by information she didn't have in the first place.

(2) Turning away from genetic determinism

In a broader sense, Coming of Age in Samoa is about nature vs. nurture and the turn away from genetic determinism. Because she proposed that culture plays just as strong a role as biology in influencing adolescent behavior, Mead’s viewpoint became a target of scientists and psychologists who emphasized nature over nurture as a determinant of behavior.

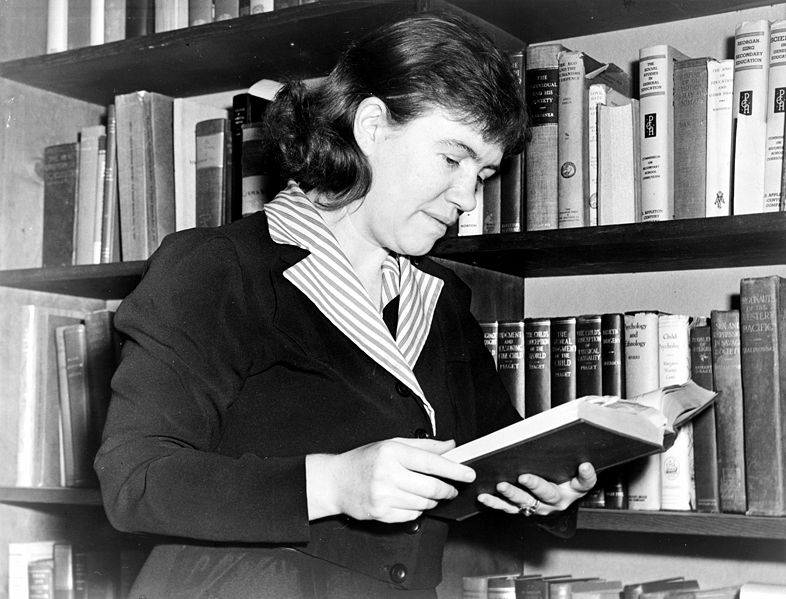

Margaret Mead published over 40 books in her 60-year career as an anthropologist

Edward Lynch on Wikimedia Commons

Mead also favored nurture and cultural influences in studies of race and intelligence. She saw that experimental psychology research that supported racial superiority in intelligence were flawed, particularly because it is difficult to measure the effects of societal structure on an individual’s IQ score. In other words, an individual’s family structure, socioeconomic status, and exposure to languages all have so much influence that it is impossible to attribute IQ scores to intrinsic ability or genetic characteristics. Language barriers, she thought, were the biggest problems in using IQ tests.

(3) Inspiring feminism

In 1930, Mead traveled to the Septik region of Papua New Guinea where she stayed for two years. She set out to determine the extent to which temperamental differences between the sexes were innate (i.e. genetically determined) or culturally determined.

Mead saw that, in the cultures she studied, male and female behaviors differed from one another, and differed from the gender roles in the US. She saw that women were dominant in societies in the Tchambuli Lake region with men less responsible and more emotionally dependent. She saw that men and women in the Arapesh were pacifists and cooperative in child rearing and farming. And she saw that in the Mundugumor region, both men and women were violent and aggressive.

She published her findings in a book, Sex and Temperment in Three Primitive Societies (1935). This book laid the foundations for the feminist movement, offering the possibility that gender roles were socially constructed and not biologically based.

(4) Addressing discrimination of lesbian and gay scientists

Mead was honored by the U.S. Postal Service with a stamp

Mead became the second female president of AAAS in 1975 (after Mina Rees in 1971). Mead was “a key figure in AAAS’ work to address social issues,” particularly in bringing up inequalities towards gay and lesbian scientists. Under her leadership, a AAAS Council noted that, “because of this discrimination, some scientists are denied the opportunity to practice their profession and others are treated unequitably in terms of salary, promotion, or assigned duties.” As AAAS president, she oversaw the passage of a policy deploring discrimination against queer scientists.

Shortly after her death, at the 1980 AAAS national meeting, there was a special session to discuss problems stemming from homophobia in the workplace. It was also at this meeting that the National Organization of Lesbian and Gay Scientists (NOLGS) was formed, now called NOGLSTP (to include technical professionals).

(Note: Mead's research practices and conclusions have been written about at length in other publications and, I believe, do not need to be unpacked all over again here. However, I just want to be clear that Mead did approach Samoa with a colonialist mindset, particularly in her use of the word "primitive," which Massive does not endorse. - Dan Samorodnitsky, science editor.)