.jpg?auto=compress%2Cformat&crop=faces&fit=crop&fm=jpg&h=360&q=70&w=540

)

The beautiful merger of art and science that inspired generations of neuroscientists

"Perhaps only an artist's eye could have seen so much in a slice of brain"

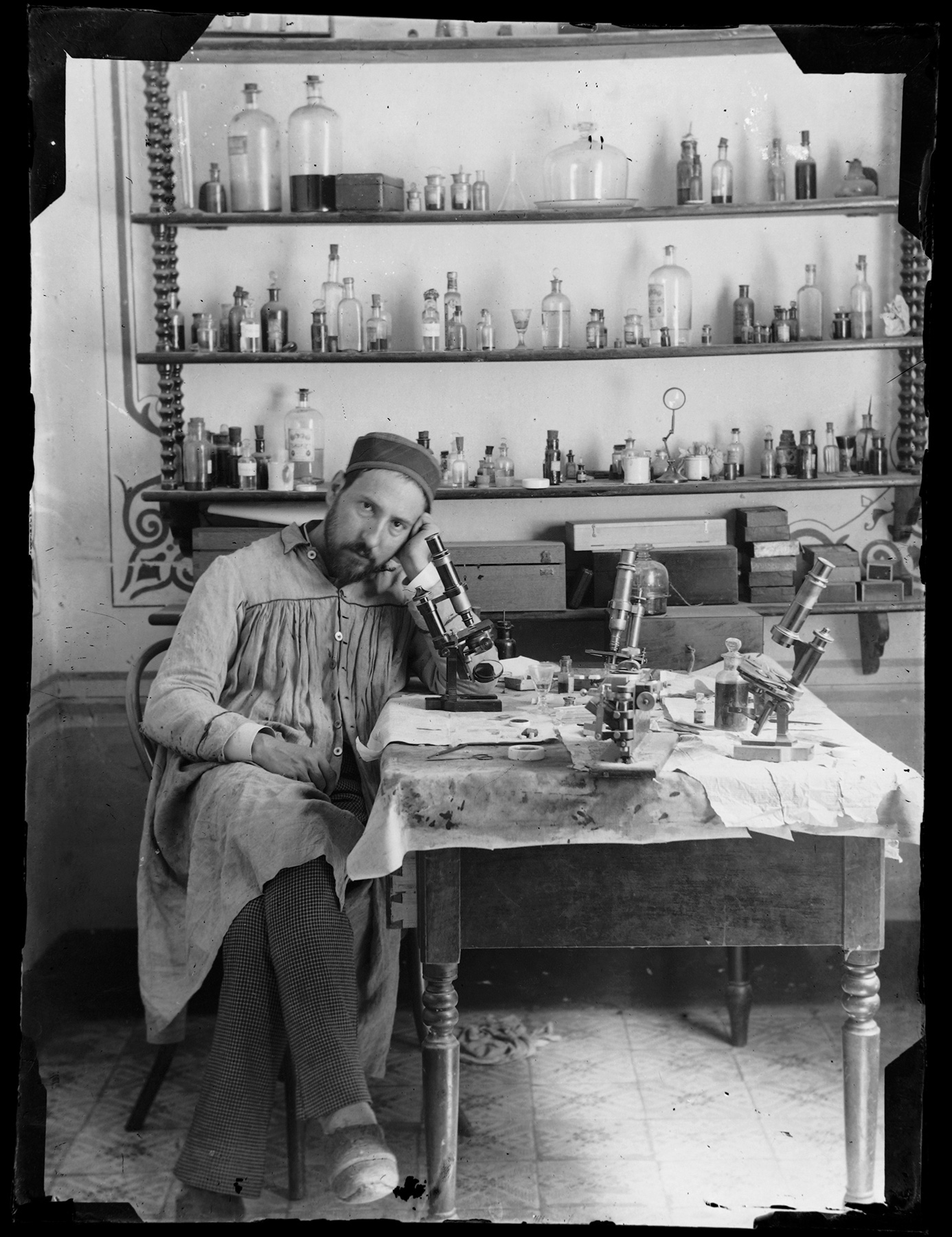

Santiago Ramon y Cajal is arresting in a photographic self-portrait captured in his laboratory in 1885. He’s in his 30s with a full beard that hasn’t begun to gray, staring down the viewer with eyes as black as the silver nitrate stains and ink drawings that have made him a fixture in every neuroscientist’s education. He’s shrouded in a smock with his elbow propped up on a crowded worktable. This is the first image as I approach the doors of the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, the gateway to a three-month long exhibit of 80 original Cajal illustrations.

I’d taken a three-hour drive with an hourlong border crossing the day after Thanksgiving. These pictures – ink drawings of neurons, translated from microscope to creamy paper – appear often in lecture slides for undergraduate neuroscience classes, but have never before made the journey from their permanent home in Madrid to North America. Although the exhibit has garnered widespread interest from the public for its artistic value alone, there's a special allure for scientists, like me.

Courtesy of Instituto Cajal (CSIC)

Seeing Cajal's drawings in person is like meeting an online friend in real life, except that this friend is very famous. I first heard of the exhibit while staying with a neuroscientist and his wife in Sydney, Australia, last April, and a coffee-table ready book that mirrors the exhibit (Beautiful Brain) has begun appearing in faculty offices around my university. The reason for the buzz is obvious. In research, we often think of ourselves as branches on a great family tree, with lineages of mentorship reaching back generations; Cajal is a spiritual ancestor of nearly every neuroscientist.

He's called the “Father of Modern Neuroscience” in part for his immaculate visualizations of the brain. As a charismatic young man raised in Northern Spain, he gravitated toward artistic expression, but familial pressure drove him into medicine. While working as a professor in Barcelona, he came across a technique called la reazione nera- the black reaction. The technique was by then 14 years old, an obscure invention of Italian physician Camillo Golgi that involved immersing slices of brain tissue in silver nitrate to reveal neurons stained black.

In his autobiography, Cajal remembered his early forays into replicating the technique: "I expressed the surprise which I experienced upon seeing with my own eyes the wonderful revelatory powers of the chrome-silver reaction and the absence of any excitement in the scientific world aroused by its discovery." Once the shapes of neurons were shown to him by the black dye, he could capture their likeness on paper.

Courtesy of Instituto Cajal (CSIC)

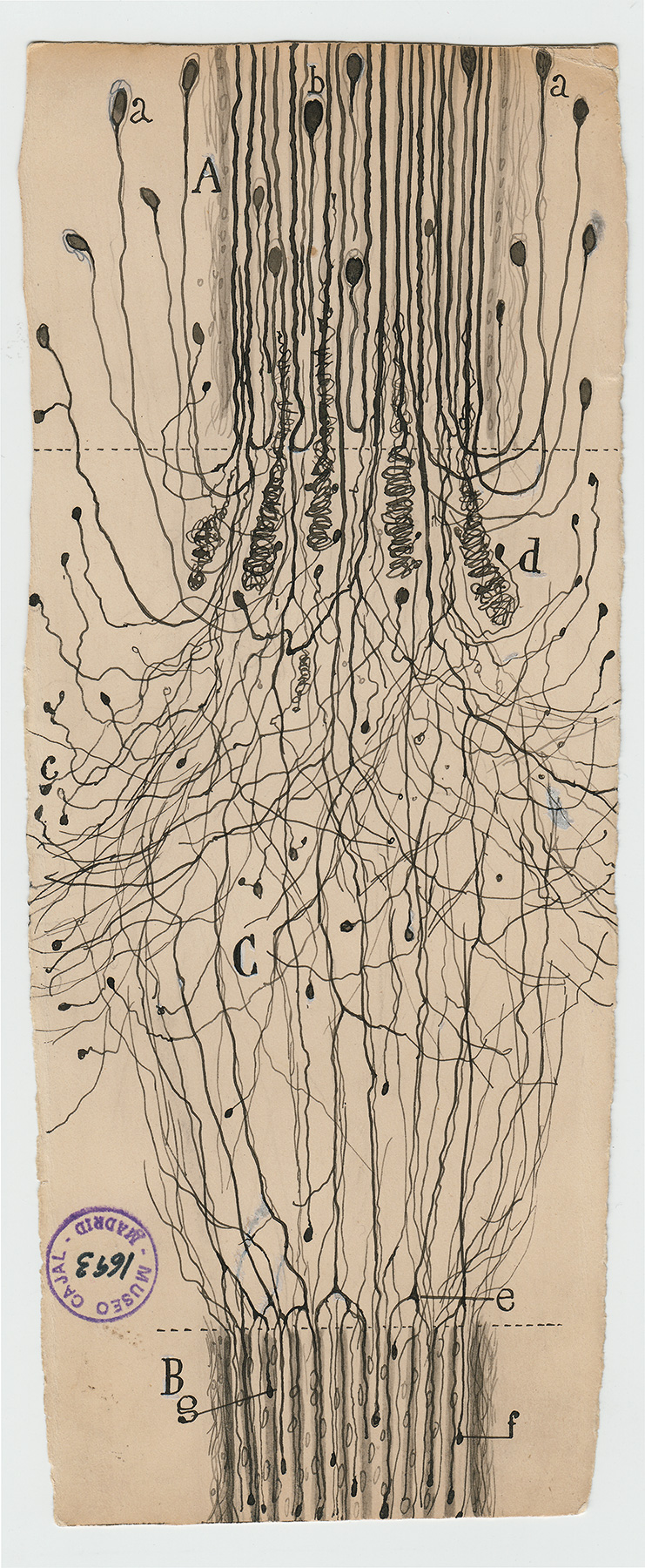

Staining neurons rendered visible a hidden world. Scientists of the day largely accepted that the brain was not composed of discrete, individuated cells but of one continuous network, a neural mass that could send signals in any which direction. Cajal’s images suggested something fatal to this theory. In slices of brains from rabbits, pigeons, and humans (to name only a few of his specimens), Cajal found neurons that appeared individuated. The scientific world would have to wait until the 1950s, until the advent of electron microscopy, to close the case for good. But more than 40 years after Cajal was awarded the 1906 Nobel prize (jointly with Camillo Golgi, in fact) for his careful work, his intuition was confirmed.

There's something eerie in the power and precision of Cajal's theories. Beyond the doctrine that neurons are individuated, he inferred correctly that they could only signal in one direction. Electrical impulses travel in an orderly way along the cell, and neural circuits have a direction by which information travels from one part of the brain to the other. He perceived from studies of developing and injured tissues that neurons were dynamic throughout their lives, changing their shapes and their complex branches as they formed networks and adjusted their connections with other neurons.

Reimagining the brain

From this reimagining of the brain, with neurons and their circuitry at the front and center, the foundations of modern neuroscience were laid.

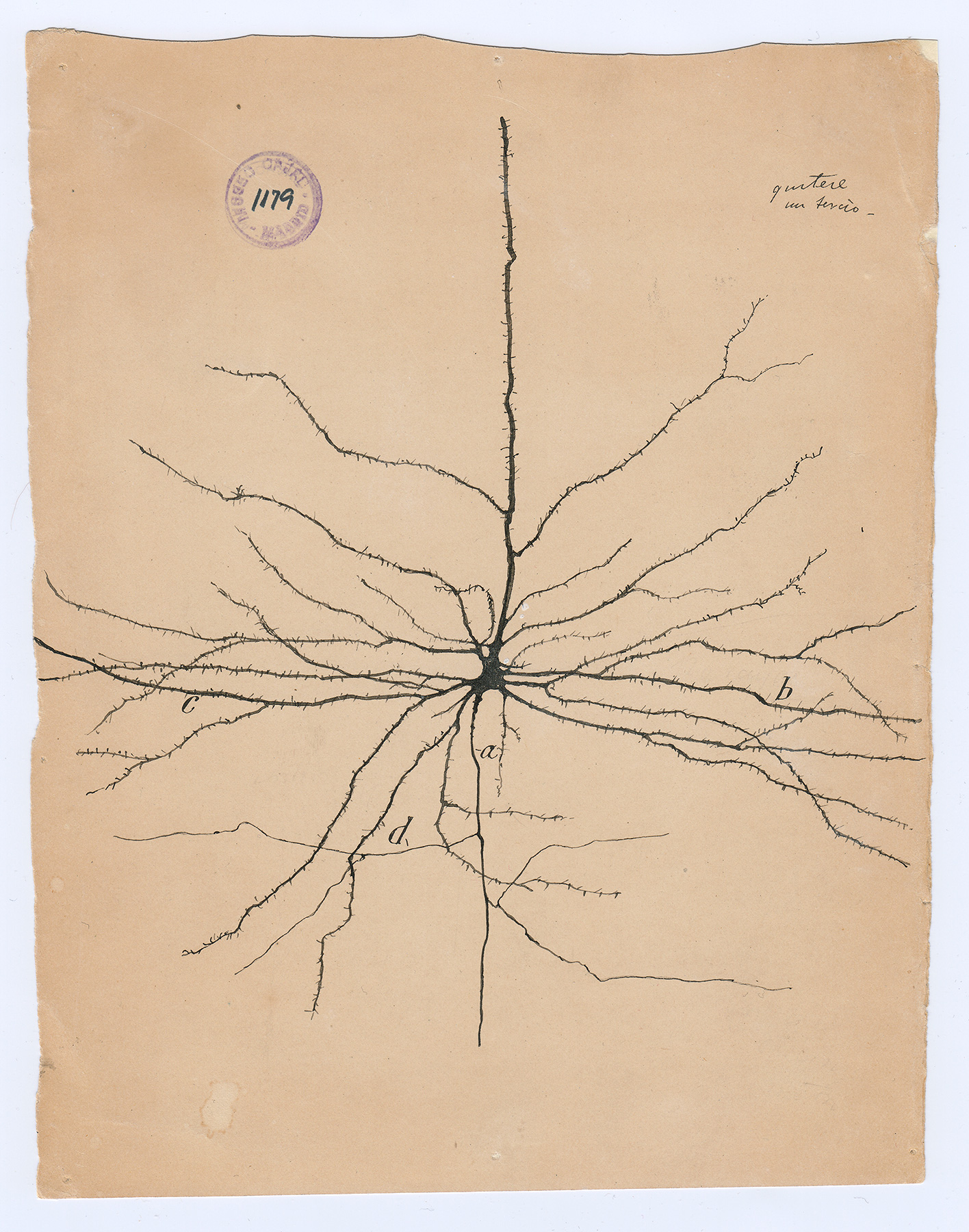

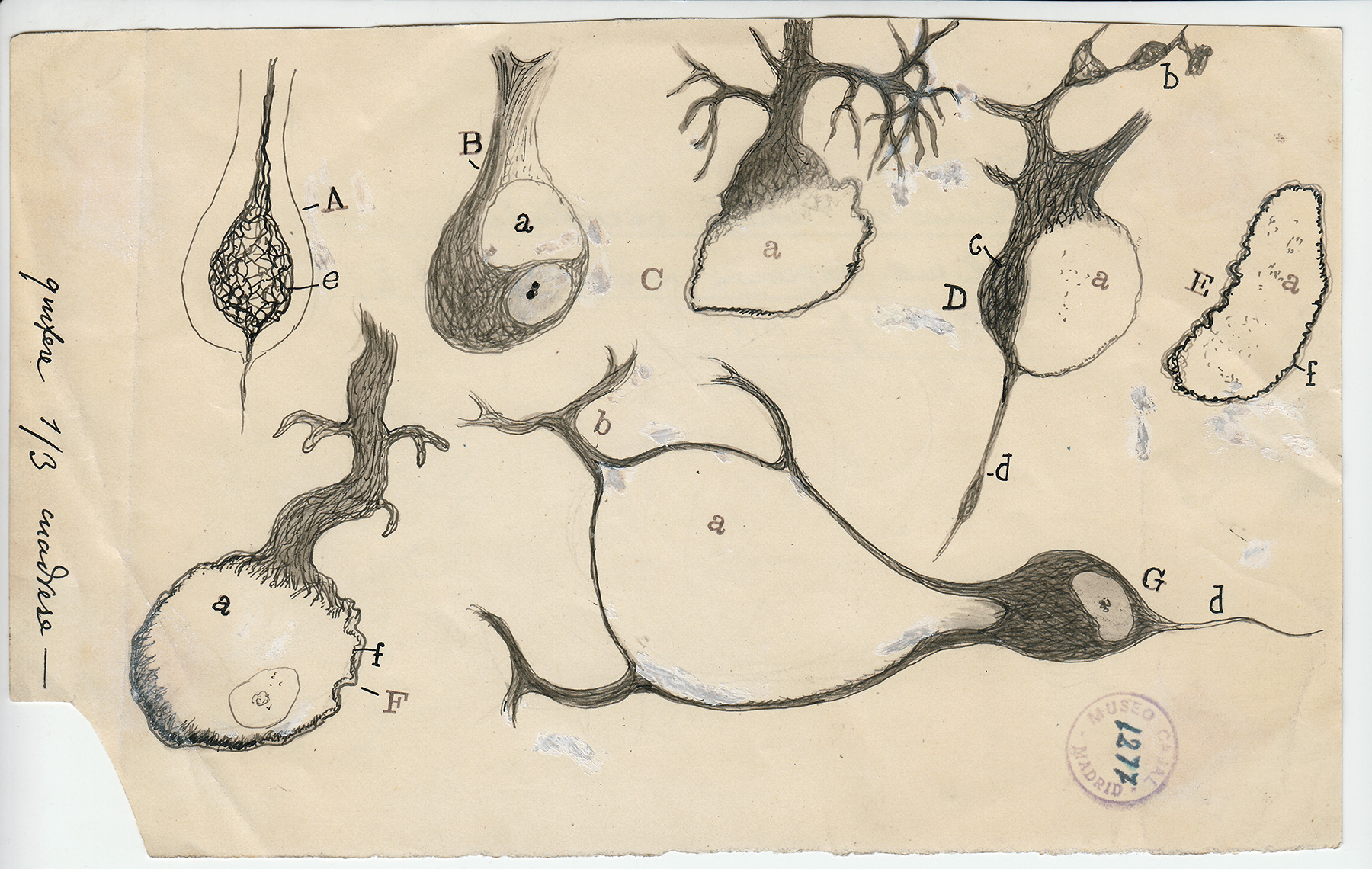

All this, from studies in looking and drawing. Wandering the gallery full of 80 small, framed Cajal drawings, curated from thousands, I'm struck with the meditative joy he must have found in the act of seeing. Many drawings are from memory, touched up with white markings to remove little branches that he decided were not really there upon a second look. Sometimes he marks hundreds of tiny spines of a cell in fine, hair-thin lines, or renders the dendritic arbor of a neuron in astounding, labyrinthine detail.

These must have taken a great deal of switching back and forth between the microscope and the page. Then there are other drawings where strokes of ink and graphite are wild tangles, obviously freehanded impressions. He captures a menagerie of neurons in a style that's both precise and playful.

Courtesy of Instituto Cajal (CSIC)

One of the exhibit guides, neuroscience student and Massive Science Consortium member Aarthi Gobinath, drew my attention to the masterful artistic ability behind Cajal's drawings. One of the most jarring experiences for a neuroscience student is to reconcile the clean illustrations of a textbook with the overwhelming commotion of real tissue. Cajal's drawings are highly accurate depictions of neurons, but they aren't exact copies of what he saw through the microscope; every one is an exercise in restraint.

"For the illustrations of a singular neuron, it required him to filter out all the background and surrounding neuronal structures," Gobinath told me. Just as she said, I can see where he has downplayed the busy cellular world supporting the elegant axons, where he's relegated some details to the background to keep the viewer's eyes on the neuron.

Outside the gallery room where Cajal's images hang, there's a collection of modern pictures of the brain. Today we can visualize brain activity with high-resolution fMRI, and we can stain thousands of neurons of a kind with targeted delivery of fluorescent proteins. It makes for compelling imagery. I recognize some of the contributors – one of the most stunning images came from the Virginia Merrill Bloedel Hearing Research Center at the University of Washington, where I worked for several years. It was taken by microscopist Glen MacDonald, and it shows a coil of cochlear cells glowing like a Christmas light show. It's worth noting that the file server used by the research center for storing thousands of microscopy images was named Cajal, and when it was my job to replace our system last year, I spent a good week agonizing over a comparably impressive name for our new machine.

Courtesy of Instituto Cajal (CSIC)

Before leaving, I settled in beside a binder of scholarly articles about Cajal. In excerpts, a personality comes into focus: a romantic and a poet who found his subject through a microscope. In his autobiography he refers to cells as "the mysterious butterflies of the soul" which reside in "the flower garden of the grey matter." Even in interviews and scientific publications, his language is immoderate and overflowing. It's a style that modern technical writing shuns.

Reflecting on his life's work of more than 12,000 drawings, it's clear he considered himself as much an artist as a landscape painter or a portraitist. "Undoubtedly," he writes. "only artists devote themselves to science … Look, here I am pursuing a goal of great interest to painters: appreciating line and color in the brain."

Like Cajal, I'd aspired to an aesthetic career as a child. And like Cajal, I was by many pressures and happy accidents turned to a different path, in the sciences. Yet today I rarely feel that my passions have been bisected down the middle. Scientists practice detachment from the outcomes of our experiments, in our best moments placing truth above validation and fame, but there's an essential place for imagination and craftsmanship – and even romance.

One of the most destructive stories we tell ourselves as a culture is that personalities are one or the other, qualitative or quantitative, artful or logical, and only one type of mind is fit for research. It isn't true in my case. It certainly wasn't true in Cajal's.

His daily devotion to staining, looking, and drawing led him to insights that eluded his contemporaries and revolutionized thinking about the nervous system. Perhaps only an artist's eye could have seen so much in a slice of brain.