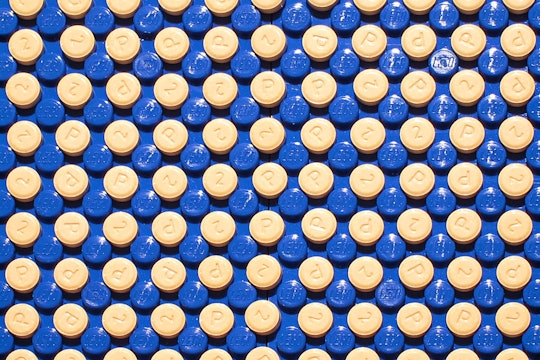

The.Comedian / Flickr

'Orphan drugs' are ascendant. What will that mean for people with rare diseases?

Niche drugs may be good for companies, but that doesn't mean they'll reach sufferers

For most drugs, the path from the Petri dish to pharmacy shelves is paved with uncertainty. It’s a decade-long journey, with billions in investment dollars at stake, seemingly countless administrative hoops to jump through, and the risk of complete failure lurking at every bend. Ultimately, studies show that only a meager 10 percent of drugs in development – about 30 per year – make it to the finish line: approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Current trends in therapeutic development are pointing to a metamorphosis in the industry. Fierce competition between companies, economic factors, policy changes, and patent expirations on existing bestsellers are nudging pharmaceutical enterprises toward a focus on a new niche market: orphan drugs, which treat diseases effecting fewer than 200,000 Americans.

Orphan pharmaceuticals have historically been left on the back burner in research and development, owing to their limited profit potential. But in the next five years, the orphan drug market is set to be worth $209 billion (an increase double that of the overall prescription drug market growth) and to represent over 20 percent of all prescription drug sales. Last year, more than a third of drugs approved by the FDA had an orphan status.

The ascent of orphan drugs as a significant portion of the drug market is the result of decades of activism. A whopping $2.5 billion is required to bring a prescription drug to market. To maximize returns, it has historically made sense to aim at the largest patient groups, with vaccines and cancer therapeutics being obvious choices. In the late 1970s, however, shifting attitudes and escalating public pressure prompted major legislative changes in a bid to prevent patients with rare conditions from being marginalized. Families and supporters of those fighting these illnesses rallied together in a coalition called the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) which, along with other advocate groups, spurred legislative action to fast-track the creation of drugs, vaccines, and diagnostic agents for rare diseases.

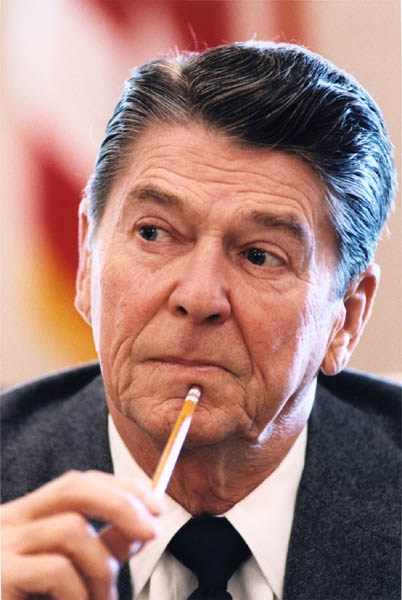

In response, President Reagan signed the United States Orphan Drug Act in 1983. Along with it came several exclusive incentives to drive therapeutic innovation: tax breaks, lowered fees, research support, and a seven-year exclusivity period for emerging therapies. For drug developers, these translated to big bucks. This package includes a 50 percent discount on research costs, which equates to $30 million a year in grants and fee waivers.

In the decades since the Orphan Drug Act was passed, a long list of mega blockbuster drugs (Viagra, Lipitor, and Plavix, to name a few) have reached the end of their patent exclusivity, creating a swell in generic drug sales. Add to that the mounting pressure on healthcare systems to slash costs: standard therapies are being consistently favored over the expensive premiums of specialty brands. This is especially so when they prove to be only marginally advantageous over their generic counterparts. To stay ahead of the curve, pharma has been force to adapt and get creative, by shifting their focus to more niche markets.

Consequently, companies are increasingly leveraging the benefits of orphan drug concessions. Pharma giants are churning out the new generation of orphan top-sellers accordingly. The sky is the limit for the commercial potential of these drugs, particularly with producers able to name their own prices. The rare disease market reports gross profit margins of 80 percent, while the pharmaceutical average hovers around 16 percent. Of the 43 blockbuster brand name drugs that raked in over $1 billion in annual profits, 18 fell under the orphan drug category.

Even smaller biopharmaceutical enterprises are getting in on the action. Enter Ultragenyx - which deals entirely in the business of solving clinical problems in the rare, and ultra-rare disease realms. Founded in 2010, Ultragenyx has been creating a buzz in the industry recently, after a winning streak of two consecutive FDA nods.

In April 2018, Ultragenyx’s gene therapy to treat Glycogen Storage Disease Type 1a got the all clear. About 6,000 individuals worldwide have this rare genetic disease, which is caused by the inability to produce the enzyme glucose-6-phosphatase. This leads to chronically low blood sugar levels, organ damage, and developmental problems. Before this, no long-term clinical interventions existed for this condition, leaving patients with the frightening reality of complete kidney failure and the risk of death. This new gene therapy involves infecting patients with a virus, which carries with it the necessary genes required to synthesize the deficient enzyme and in doing so resolve their ability to metabolize glucose.

With this feather in their cap, Ultragenyx almost immediately hit yet another home run with Crysvita. This drug supports those with an inherited form of rickets, called X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH). In this debilitating disease, inadequate phosphorus levels lead to bone deformity, mobility issues, and excruciating pain. Crysvita harnesses the body’s immune response through antibodies to impede the secretion of phosphorus in XLH patients. Such medical breakthroughs are much-needed rays of hope for those with rare diseases, many of which have a genetic basis and are usually both chronic and life threatening.

Despite the generous governmental backing, however, creating diagnostic and treatment procedures for these conditions remains no small feat. Tiny patient populations mean insufficient participant numbers for robust safety and clinical trials. Couple that with the extensive logistical and geographical hurdles for coordinating patients, doctors, scientists, pharma companies, and support groups. That orphan drugs are starting to look like cash cows regardless is telling when it comes to evaluating the state of drug development.

With the shifting sands in drug development comes questions and criticism surrounding the orphan drug revolution. How rare diseases are defined and prioritized remains an issue of debate. Also, what are the implications of emerging orphan drugs on our healthcare systems? And, who decides on how these drugs are priced? Even in the best-case scenario, an approved drug usually comes with a hefty price tag. Crysvita, for example, costs a whopping $200,000 a year, and that's after rebates. This leaves patients with the heartbreaking possibility that an effective treatment may remain just out of reach while drug companies reap massive windfalls that considerably surpass their initial investments.

Bolstered by profit margins, policy, and positive public perceptions, it seems the appeal for industries to tackle rare conditions is only growing. The "one size fits all" approach to cure the masses is steadily being replaced with a focus on personalized medicine and defined patient groups. Still, the sheer level of biological complexity and the diversity of these diseases is staggering. Despite movement in a positive direction, many patients will likely remain waiting for the light at the end of the tunnel.