5 facts about Frances Hamerstrom, wildlife biologist, hunter, and savior of the prairie chicken

As a kid, she dissected blue jays and built a garden whose path was lined with poison ivy

If you wake up bright and early on a chilly April morning and quietly hide in the frost-covered grasslands of Wisconsin, you might get lucky. With patience, binoculars, and a discrete lookout spot, you might spot the Greater Prairie Chicken stomping its feet, inflating its bright orange air sacs, and projecting a deep and pulsating 'whoooo' into the morning air. The performance is a carefully constructed mating ritual called "booming," and attracts hundreds of viewers each year.

You wouldn't have any luck doing this, though, if it weren't for Frances Hamerstrom.

Throughout her prolific career as a wildlife biologist and conservationist, Hamerstrom studied various species of birds and prey in the US as well as Mexico. She is most often recognized for her valiant effort to save the prairie chicken. We love her for this reason, as well as many others.

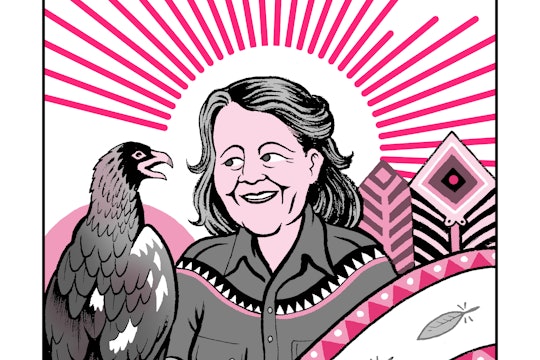

Matteo Farinella

To her parents’ dismay, she showed a very early interest in the outdoors

Hamerstrom, born Frances Flint in 1907, was not a well-behaved daughter – at least, not in her era. Despite her upbringing in a house of Boston socialites, she didn’t want to dance, or make lace, or walk with a book balanced on her head. Instead, she’d regularly sneak out of the house to sleep in the fields at night and wake up with the birds at dawn. Occasionally, she’d bring home a dead blue jay and dissect it. She built a garden behind her family's house, and lined the path to it with poison ivy – she was immune; her parents weren't.

Hamerstrom dearly loved natural history museums, and began her own collection of insects and other creatures in jars. She wasn’t taught about natural history in school, yet at age 11 she read The Origin of Species by Charles Darwin.

She was one of the first female wildlife biologists

Hamerstrom dropped out of high school as well as Smith College – a move which she was rather proud of, since she found the classes at Smith to be boring. She ultimately earned a bachelor's degree from Iowa State University in 1935. It was there that she met her future husband, Frederick Hamerstrom, who also wanted to be a naturalist. After graduating, they moved to the University of Wisconsin at Madison, where they studied with famous conservationist Aldo Leopold. Hamerstrom was Leopold's only female graduate student. She received her master's degree in wildlife management in 1940.

Spontaneous Fran and methodological Frederick soon became an inseparable conservation team. However, at the time there were almost no women in wildlife biology, and many people had trouble acknowledging that she was a biologist in her own right. “Most administrators were afraid to hire a female biologist,” she says in her autobiography. Often, this meant that Fred was paid while Fran was considered a volunteer.

Her research helped save Wisconsin's prairie chickens

In the mid-1900s, prairie chicken populations in Wisconsin were rapidly dwindling to near extinction, even though they weren't being hunted. The Hamerstroms spent more than 40 years watching the greater prairie chicken – not a proper chicken, exactly, but a grouse – to figure out how to save them. In a landmark study for the importance of habitat conservation, the Hamerstroms discovered that the disappearance of grasslands was causing diminishing populations of prairie chickens. The Hamerstroms issued an urgent call for private and government groups to preserve and restore grassland habitats. As a result of their research and activism, prairie chickens and many other grassland species are still around today.

Hamerstrom and her husband lived in a pre-Civil War 240-acre farm without running water in Plainfield, WI, and began running conservation programs for individuals (called "gabboons") who wanted to learn how to preserve local wildlife and help count prairie chickens. Over the years, she invited thousands of apprentices to sit in the freezing cold with her and watch the ritual displays of male prairie chickens. Others would come to see her, an expert falconer, throw mice into the road to attract a large falcon. The Hamerstroms made an effort to train a diverse crew of gabboons hoping that they could then go back to their homelands and develop their own conversation programs.

She was a fantastic hunter – and she was really into it

Hamerstrom’s father was a hunter with three sons, none of whom had any interest in following suit. But his “slim, blonde daughter” sincerely wanted to learn the trade, and showed early promise with a pistol. Still, she was terrified of her father, and he never learned of her eager interest in hunting, likely because he couldn’t even imagine that a woman would want to learn how to hunt.

Hamerstrom eventually developed hunting skills on her own, often by sneaking out with her father’s equipment, or ice cream to grease her guns, and found it to be completely pleasing and all-encompassing. She summarized her love for hunting and the trials of a female hunter in her witty book, Is She Coming, Too?: “For me, hunting is not symphony, not a painting, not to be defined. It is a long fascinating road leading to moments of ecstasy.”

She wrote 12 books and over 150 scientific papers

In addition to writing about hunting, Hamerstrom thoughtfully tackled topics from falconry to how cook in the wild. She was an incredibly prolific scientist with papers on various species of bird, deer, and rodents. But perhaps her most fascinating works are the first-hand accounts she provides in her numerous books. They give unprecedented insight into the mind of a woman who absolutely loved watching nature.

In Harrier, Hawk of the Marshes, Hamerstrom describes the interplay between hawk and vole populations and her conclusion that male hawks bred much more, and at earlier ages, when there were plenty of voles around. In one fell swoop, she summarizes her incredible work: "It took me more than 25 years to find these things out and, of all things, to look upon the vole as an aphrodisiac."

Hamerstrom raised her two children the way she probably wished she was raised: with plenty of wildlife interaction and freedom to explore. For an entire year, she went on monthly full-moon adventures with her children and wrote about each of these in a beautifully-illustrated children's book titled, Walk When the Moon is Full. Her book continues to inspire others to do the same.

Even into her 80s and after her husband's death, Hamerstrom continued to travel the world. At 86, she traveled to Peru to watch black-collared hawks capture fish. But Hamerstrom wanted to see humans hunt the fish as well, and one year later she went back to observe indigenous hunters there.

Hamerstrom died at the age of 90 in 1998, but not without accomplishing her biggest life goals. “When I was a child, I had two dreams: I wanted to live with wild animals, and I wanted to marry a tall, dark man. I did both.”