A nuclear attack could be a lot like an asteroid strike

Nothing compares to the impact that killed the dinosaurs, but nuclear blasts are far more likely

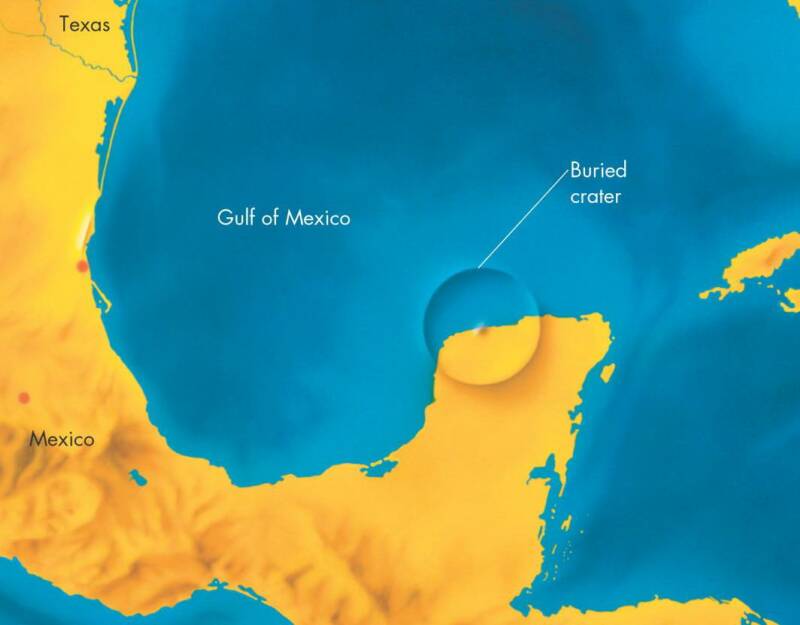

Although it is highly unlikely for a large asteroid to come in contact with Earth, it does happen once in a while. Consider southern Mexico: one day, 66 million years ago, an asteroid around 6.2 miles in diameter created the Chicxulub crater in the Yucatan Peninsula. The asteroid's diameter was slightly larger than Mt. Everest is high, or 12 times the size of the largest human-made structure in the world. The impact and subsequent changes in global climate caused the Cretaceous-Paleogene (or K-Pg) extinction. In other words, it killed the dinosaurs, melted rocks, and created a mega tsunami; it also happens to be my favorite event in geologic history.

If that asteroid were put on today's commonly used Torino Impact Hazard Scale, which is based on how likely it is for the asteroid to hit Earth and how large (and therefore how powerful) it is – an object rated zero poses no hazard and 10 is "capable of causing global climatic catastrophe that may threaten the future of civilization as we know it" – it would be a 10. Even the largest nuclear weapon ever designed does not come close to creating the widespread geographic effects that the asteroid impact had.

Dementia / Flickr

And yet, studying asteroids is one of the most promising ways to predict the effects of a nuclear explosion in an increasingly hostile world. Even with the difference in size between detonations and asteroid impacts, there are more parallels than you might think. They create similar minerals, generate pressure waves, and have the potential to dramatically shift climate. This is true even for smaller nuclear weapons, as the secondary effects of the bombs (including famine) would be devastating. As we start to learn more about asteroids, including the Chicxulub impact, we are also learning more about the potential effects of nuclear weapons.

Asteroids, Hawaii, and odds

In 2016, a group of geologists on International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Expedition 364 headed out to the Chicxulub crater in search of new data from the impact. They drilled a long sediment core from the impact crater, which has provided new insights into the angle and direction from which the asteroid came.

Natalia Artimieva, senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute in Tuscon, AZ, wasn't on the expedition, but she spends most of her time using computer models to figure out what happens when flying objects hit planets. She collaborated with Joanna Morgan, professor of geophysics at Imperial College London and co-chief scientist of Expedition 364, and the rest of the Expedition's scientists to model the impact using their new data.

They calculated that the impact would have released vast amounts of sulfur and some carbon dioxide gas, yielding more global cooling than calculations from the late 90s had. This new research, which was published in Geophysical Research Letters in October, demonstrates how any asteroid impact with enough energy could have global consequences. The asteroid hit northern Mexico, but the gas released by the impact spread throughout the entire atmosphere.

I was in Hawaii with my family when the missile launch false alarm occurred in January. I was about to eat breakfast when my phone played a loud alert sound, which I initially thought was an alarm I had forgotten to turn off. Now that we all know there was never any danger, it sounds a little silly, but for 20 minutes, I was listening for sirens and explosions. I realized how lucky I was to have absolutely no idea what to do; I haven't grown up fearing incoming missiles. The only reason I was able to stay a little bit calm was that I was with my immediate family; I had a moment where I thought, "At least we will be together."

When we finally found out that there was no incoming threat (thanks to Twitter, not an official alert, which came after another 20 minutes or so), everyone relaxed, but the risk of nuclear war has stayed on my mind since then. As a graduate student, my first reaction to most events is to do some research, so I started learning about the US missile defense system in the context of the false alarm (you can listen to the terrifying audio alert in the introduction of this podcast). I was shocked by what I found: essentially, it is more likely for there to be a nuclear missile detonation than an asteroid strike in the next 100 years. A large explosion could have a similar effect as the Chicxulub asteroid impact, where gases are released and global climate is fundamentally altered.

Cosmology and security

When I got back from my trip, I spoke with Laura Grego, a senior scientist in the Global Security Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), about nuclear weapons and asteroids. Laura is a physicist who studies space security and missile defense now, but she used to do cosmology research; she was the perfect person to talk to about this.

Wally Gobetz / Flickr

Grego explained to me that nuclear weapons are supposed to act as a deterrent against other types of attacks. Just having such powerful weapons is supposed to be enough to stop potential aggressors. But recently, "there has been more discussion about actually using nuclear weapons, which was never supposed to be on the table," Grego said. In addition to intentional strikes, erroneous detection or accidental detonation could trigger a global nuclear war. In 2010, the US launch center temporarily lost "complete command and control" of 50 intercontinental ballistic missiles; in 2007, six armed cruise missiles were accidentally loaded onto a plane in North Dakota and it took 36 hours to detect the mistake.

In comparison, the modern US planetary defense system has only missed one major detection. In 2013, a previously undetected asteroid disintegrated over Chelyabinsk, Russia with an explosion that shattered glass for miles. That said, the asteroid was small (55 feet) and did not impact the surface of the Earth, so the only benefit of prior detection would have been alerting emergency services in advance of the explosion. NASA estimates that 80 to 100 tons of material – 11 times the weight of a T-rex – falls onto Earth's atmosphere every day as dust and tiny asteroids, so they certainly have their hands full.

While asteroids could hit anywhere on Earth, including open ocean, nuclear warheads are specifically designed to hit population centers. In that way, even though the asteroid that hit the Yucatan was much larger than nuclear weapons, the potential loss of life and property is still huge. It is difficult to quantify the risk associated with nuclear weapons, because it remains highly unlikely that the weapons will be used, either intentionally or accidentally. But the probability is not zero, and they have the potential to create so much destruction.

A long list of high risk

Some of the proposed uses for nuclear warheads, including geo-engineering to mitigate climate change and asteroid deflection, seem reasonable at a surface level. They might even sound promising enough to warrant keeping an inventory of the weapons. To me, the long list of near-misses and potential for global devastation makes it far too risky.

"I certainly don't think it is a long-term strategy for human beings to have nuclear weapons and assume they will never be used," Grego explained to me. But she also pointed out that one of the important differences between bombs and asteroids is that everyone has the power to advocate for fewer nuclear weapons, increased diplomacy efforts, and better safeguards against accidental detonations, but we can't influence where asteroids are going.

Coming face-to-face with a potential missile attack made me aware of how important this issue is, and what is at stake. As much as I love learning about the Chicxulub impact, I hope humans never come anywhere close to replicating it.

I like the idea of comparing the impact of asteroids and nukes, but I’m not convinced that you show that nuclear attacks have become more likely. Is there any concrete analysis apart from your conversation with Dr. Grego that shows this? And that asteroids are less likely? For one, the list of nuclear accidents, like the ones you point out, seems to show that these have become less frequent since the 1980s, and especially since the Cold War. Color me an optimist!

I know you don’t get into policy and the Non Proliferation Treaty, but I just wanted to point out that the NPT has failed primarily due to the fact that

1.It’s discriminatory and

2. the US and Russia as the strongest nuclear powers have done little to lead by example. (Coming from India, a non-NPT nuclear state, and one which is probably the most likely to face nuclear confrontation, this is a topic that’s always been pretty real to us.)

As an aside, and in case anyone has read this, here’s an even more terrifying possibility than either nuclear war or asteroids 😨