Meet Virginia Apgar, the unlikely anesthesiologist who saved newborn babies

Apgar's simple, standardized score helped decrease the startlingly high infant mortality rate

The newborn’s skin was blue and he wasn’t breathing. A few years earlier, the doctors would have documented the baby as stillborn, not believing there was anything they could do to help. If this were the mid-1950s though, a recent development in the field of obstetrics would have given them hope – the Apgar score. The newborn’s 1-minute Apgar score indicated that the newborn was in poor condition, but they treated him with oxygen. Sure enough, his 5-minute Apgar score showed improvement. Maybe he had a chance after all.

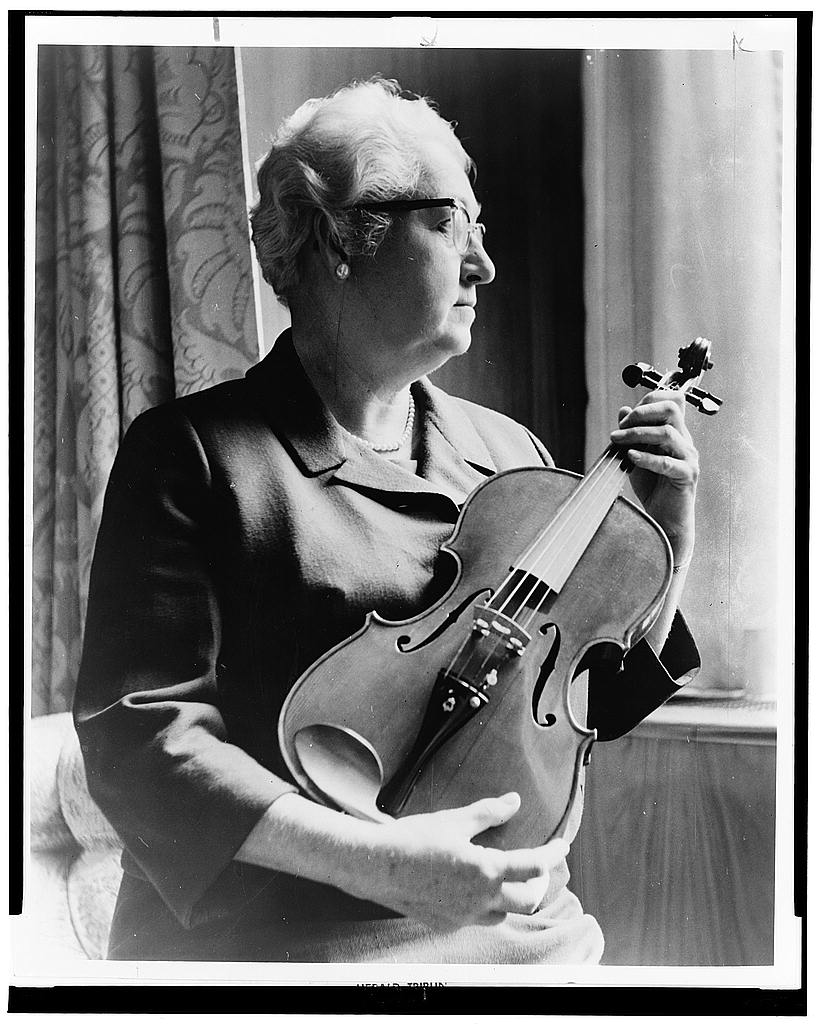

Virginia Apgar's invention helps saves newborns.

Virginia Apgar was born on June 7, 1909 in Westfield, New Jersey. Although her father’s day job was that of an insurance executive, on the side he was an amateur inventor and astronomer. As a child, Virginia Apgar learned to play the violin and later joined her high school orchestra. Around this time, she set her sights on medicine. At Mount Holyoke College, she pursued a degree in zoology and was lauded as an exceptional student.

After graduating in 1929, Apgar began her medical training at Columbia University's College of Physicians and Surgeons. Women were drastically underrepresented in the field at the time; there were only eight other women in her class of 90 people. After completing her MD in 1933, she became one of the first female surgical residents at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. However, her mentor, surgeon Allen Whipple, was concerned that since she was a woman, she would have a hard time attracting patients. As a result of this feedback, Apgar pivoted to anesthesiology, a relatively new specialty established in the mid-1940s. This was a much less prestigious career path, but since anesthesia was mostly handled by nurses at the time, gender discrimination wouldn't present as much of a hurdle.

Virginia Apgar examining a newborn

As an anesthesiologist, Apgar had never even delivered a baby and was therefore an unlikely candidate for revolutionizing the field of obstetrics. However, part of her job entailed providing anesthesia for deliveries, so she had plenty of exposure to newborns. In the 1950s, reducing infant mortality (the death of an infant before their first birthday) was a daunting problem: an astonishing one in 30 newborns died at birth.

At that time, if a newborn didn’t seem to be thriving – if, for example, the baby’s skin was too blue or they were deemed too small – the baby would be left to die and documented as a stillborn. Of course, it wasn’t that anyone wanted these babies to die, but doctors simply believed that they were too sick to survive. Apgar believed that if such babies received better care, many of them would live.

Since Apgar was a “lowly” anesthesiologist, she wasn’t in a position to directly challenge how obstetricians did their work. Moreover, she was a woman in a man’s world. Nevertheless, she devised the "Apgar score" – a way to observe and document the condition of every newborn. It was a simple, indirect approach that had powerful results in terms of helping to dramatically decrease the infant mortality rate.

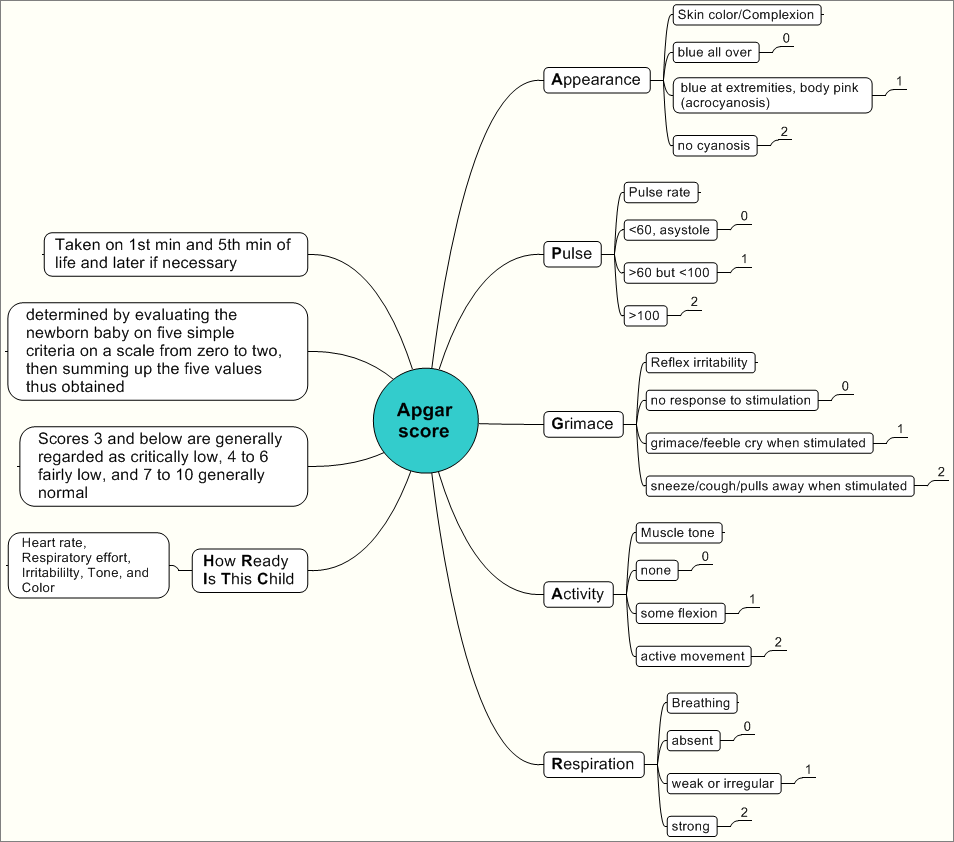

A chart for calculating a newborn's Apgar score

Via Wikimedia

The Apgar score is an acronym with each letter standing for a component of the score: Activity, Pulse, Grimace, Appearance, and Respiration. In other words, the score evaluates a newborn’s movement, heart rate, irritability, color, and breathing. In each category, a newborn receives 0, 1, or 2 points. In the “Pulse” category, for example, the newborn’s pulse may either be absent (0 points), below 100 beats per minutes (1 point), or over 100 beats per minute (2 points). The total score ranges from 0-10, with a low score indicating a newborn in poor condition, and a high score indicating a newborn in excellent condition.

The Apgar score enables healthcare providers to systematically observe and document the condition of every newborn – starting one minute after the baby is born and again five minutes after birth. Implementing the Apgar score introduced a spirit of competition because the doctors inherently wanted the newborns they delivered to have better scores. It became readily apparent that a baby with a low score initially could improve remarkably and have an excellent score five minutes after birth.

Moreover, Apgar worked with colleagues such as pediatrician L. Stanley James and anesthesiologist Duncan Holaday to establish the physiological basis for the Apgar score’s profound effect on reducing infant mortality. By analyzing neonatal blood chemistry, such as the oxygen and carbon dioxide levels in the newborn's blood, Apgar and others were better able to correlate a newborn’s Apgar scores to the effects of labor, delivery, and maternal anesthesia practices. Today in the US, thanks in large part to Apgar’s contribution to the field of obstetrics, only about three out of five hundred newborns don’t live to see their first birthday.

Today the Apgar score remains the standard of care, although some have wondered whether or not it is still pertinent in the context of modern medicine. However, despite suggestions that the Apgar score may be antiquated, this study from 2013 concluded that the Apgar score “has continuing value for predicting neonatal and post-neonatal adverse outcomes.”

Apgar, a musician as well, examining a violin "fashioned from an old telephone shelf"

In the process of attending over 17,000 births, Apgar had seen many newborns with birth defects, and she went on to become a leader in the emerging field of teratology – the study of birth defects. In 1958, she took a sabbatical from clinical practice and pursued a master's degree in public health from Johns Hopkins University. Subsequently, she became the director of a division at what is now the March of Dimes. In this role, Apgar worked to increase research in the field of teratology in order to help prevent and ameliorate birth defects to the greatest extent possible. Her medical training coupled with incredible determination and perseverance enabled her to leave an inspiring legacy in the field of medicine.

Apgar never retired, but she developed progressive liver disease and died on August 7, 1974. In addition to receiving numerous awards during her lifetime, her contributions have also been recognized far and wide posthumously. In 1994, her portrait was included in the commemorative U.S. postage stamp series of “Great Americans.” The following year, Apgar was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.