Geologists find evidence of two new supervolcano eruptions at Yellowstone

Their trends suggest that the next eruption won't happen for a long time

Some 8.7 million years ago, much of what is now Idaho was torched by clouds of hot volcanic ash, destroying all vegetation and animals in sight. The supervolcano, Yellowstone, was erupting. This was Yellowstone’s largest eruption on record.

Super-eruptions can decimate entire regions, and their cocktail of ash and gases can alter the climate. But, even though they eject huge amounts of material, there are very few documented super-eruptions in the geologic record. So we don’t fully understand why they are so big or how often they occur. Now, details of the Yellowstone supervolcanic eruption are documented in a new study published in the journal Geology.

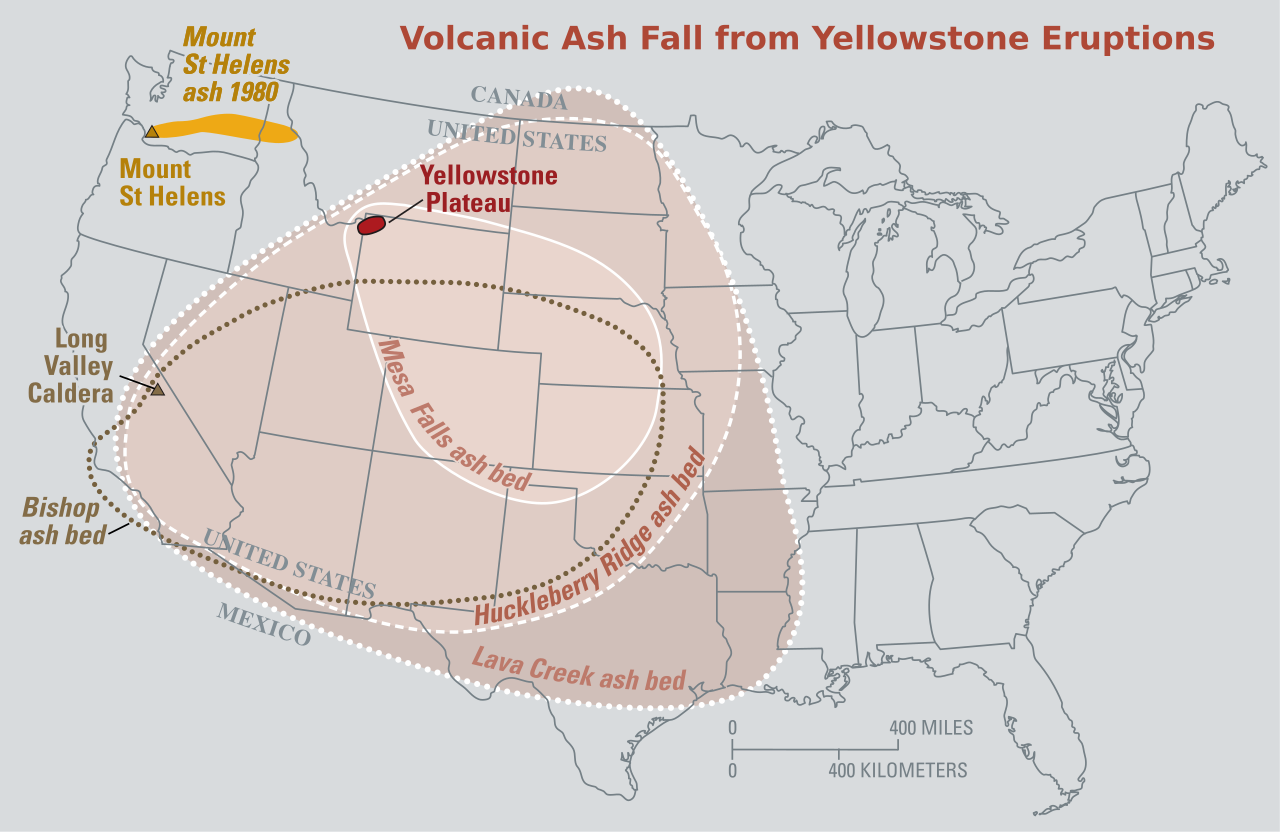

Yellowstone’s ancient eruptions scattered volcanic debris across the northwestern US. There are so many deposits — covering tens of thousands of square kilometers — that it can be difficult to tell each eruption apart. To get around this, volcanologists collected detailed identifying information, including chemical and chronological data, on each geological deposit.

Volcanic ash from Yellowstone. Not pictured: molten or liquid glass

Wikimedia

When they looked at the data, they found that much of the volcanic debris, which was thought previously to come from repeated smaller eruptions, had the same chemical makeup and age. In fact, these deposits were produced by two previously unrecognized super-eruptions. Both eruptions were searingly hot and would have baked the landscape in a thick coating of molten volcanic glass. The youngest of the two, known as the Grey’s Landing super-eruption, is dated to roughly 8.7 million years ago, and, according to the volume of debris released, is 30% larger than all other eruptions recorded from Yellowstone.

Recognition of these events brings Yellowstone's total number of eruptions during the late Miocene to six. That makes for one eruption about every 520,000 years. Since then, however, the pace of eruptions has slowed to once every 1.5 million years.

The evidence seems to suggest that Yellowstone is slowing down. And if this trend continues, the next super-eruption won't happen for another 900,000 years. Predicting eruptions is however a risky business, and the United States Geological Survey still maintains a permanent monitoring network on Yellowstone — just in case.