Via Wikipedia

Meet Betty Hay, the scientist who saw how cells grow and limbs regenerate

Happy birthday to the trailblazing developmental biologist

Limbs regenerate, embryos grow, and cancers invade.

In each of these processes, cells change dramatically. Betty Hay studied fascinating biological phenomena, relentlessly asking questions with her students and colleagues to understand how cells behaved. By the end of her life, she had made enormous research contributions in developmental biology, on top of committing herself to mentoring the next generation of scientists and advocating for more representation of women in science.

She made significant contributions towards understanding cell and developmental biology

Betty Hay began as an undergraduate at Smith College in 1944. She loved her first biology course and started working for Meryl Rose, a professor at Smith who studied limb regeneration in frogs. “I was self-motivated and very attracted to science,” she said in an interview in 2004, “Meryl at that time was working on regeneration and by the end of my first year at Smith I was also studying regeneration.”

Hay regarded Rose as a significant scientific mentor in her life and followed his advice to apply for medical school instead of graduate school. She ended up attending Johns Hopkins School of Medicine for her medical degree while continuing her research on limb regeneration over the summers with Rose at Woods Hole’s Marine Biological Laboratory. She stayed at Johns Hopkins after to teach Anatomy and became an Assistant Professor in 1956.

The year after, she moved her studies to Cornell University’s Medical College as an Assistant Professor to learn how to use the powerful microscopes located there. Her goal was to use transmission electron microscopy (TEM), a method of taking high-resolution images, to see how salamanders could regenerate an amputated limb. “Nothing could’ve kept me from going into TEM,” she said later.

With her student, Don Fischman, they concluded that upon amputation, cells with specialized roles, known as differentiated cells and thought to be unchangeable, were able to de-differentiate and become unspecialized stem cells again. These cells without an assigned role could then have the freedom to adopt whatever new roles they required to regenerate a perfectly new limb.

Already making leaps in figuring out an explanation for the process of limb regeneration, Hay turned her attention from salamanders to bird eyes when she moved to Harvard University. She studied the outermost layer of cells on the cornea, known as the cornea epithelium. With the help of a postdoctoral scholar in her lab, Jib Dobson, and a faculty colleague, Jean-Paul Revel, they isolated, grew, and took pictures of cornea epithelium cells and demonstrated the epithelial cells could produce collagen.

Collagen is the main type of protein that weaves together to form the extracellular matrix, a connective tissue (the “matrix”) found outside of cells (“extracellular”). The collagen in the extracellular matrix provide structure, acting as a foundation for connective tissues and organs such as skin, tendons, and ligaments. Other scientists in the field were skeptical of the conclusion. They thought that one dedicated cell produced collagen, and nothing else. They dismissed the idea that cells in the cornea could somehow do the same. Despite their doubt, Hay, along with postdoctoral scholar Steve Meier, continued their studies. In 1974, they further showed that not only could epithelial cells produce collagen and extracellular matrix in different organ systems, but that the matrix could also tell other cells what type of cell to become.

She was a committed educator and mentor

Kathy Svoboda and Marion Gordon, two colleagues of hers, wrote about Betty Hay and described her “not only as a superb cell and developmental biologist, but also as an educator and beloved mentor.”

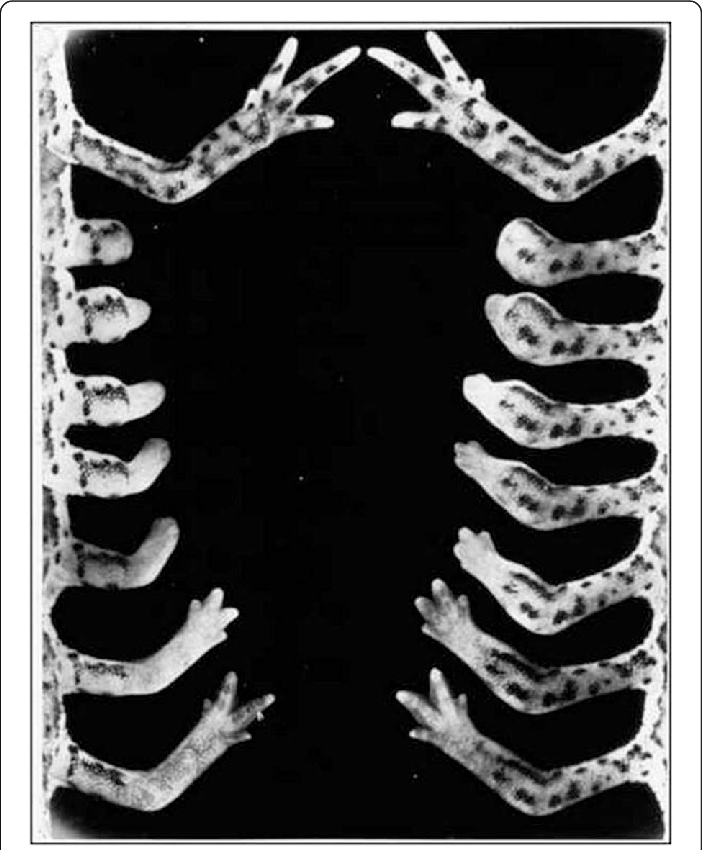

Limb regeneration in salamanders

Russell et al BMC Biology 2017

She was dedicated to teaching and influenced the careers of many junior and early-career scientists. In addition to working with and training her students to produce successful research and results, others mentioned how she would take the time to introduce students in her department to more established and prominent scientists in the field of cell biology. These actions reflected her belief that every student was worthy of being heard and introduced.

She held influential positions and advocated for more representation of women in science

At the time of her graduation from Johns Hopkins in 1952, she was one of only four women in her graduating class of 74 people. Afterwards, she experienced frequent moves for her career, going from Baltimore, to New York, to Boston. Despite how difficult it felt moving alone and leaving her personal relationships behind every time, she felt it was necessary for her career. In her mind, she strongly believed her research always came first, fueled by her “intense desire to find answers, using the scientific approach.”

She went on to serve as president for multiple professional societies, such as the American Association of Anatomists, the American Society for Cell Biology, and the Society for Developmental Biology, demonstrating her commitment to leadership and service. In two of these societies, she was the first woman to ever hold the position.

In 1975, she became the first female chair of what is now the Department of Cell Biology at Harvard University and held that position for 18 years. Even with these impressive milestones, she acknowledged one of her biggest obstacles to be achieving acceptance in the male professional world.

In 2004 and nearing retirement, Betty Hay would go on to say, “I am very glad to see in my lifetime the emergence of significantly more career women in science,” in an interview with editor-in-chief Fiona Watt for the Journal of Cell Science, “this so enriches the intellectual power being applied to the field of cell biology.”