People with narcolepsy process humor differently

A good joke or sudden surprise can trigger muscle weakness

Italian and Norwegian researchers have shown, via brain imaging, how people with narcolepsy experience humor differently than neurotypical people.

Ever since narcolepsy was first identified in the 19th century, neurologists have observed that amusement or other positive emotions can trigger a distinctive symptom of the disorder. This symptom is called cataplexy, or temporary muscle weakness. Full-body cataplexy may make someone collapse, but it can also be more subtle, affecting just the legs, arms, or face.

Narcolepsy develops as a result of autoimmune attack on brain circuits that regulate sleep and wake. Cataplexy is thought to come from the paralysis that accompanies REM sleep, which usually keeps people from acting out their dreams. In people with narcolepsy, the paralysis seems to spill over into waking time. They remain awake and aware while cataplexy occurs. Studying cataplexy helps us understand the connections between the parts of the brain that regulate emotions and REM sleep.

University of Bologna neurologists have been having children and teenagers with narcolepsy watch short movies -- Roadrunner and Coyote cartoons or YouTube cat videos, for example. They asked study participants to choose between a few funny videos. For each, a video that worked well was shown while the young subjects were wearing EEG electrodes and inside an MRI scanner. This complicated arrangement was needed to observe cataplexy in a setting where it could be recorded.

EEG being performed on human volunteer

Alexhvl15 on Wikimedia Commons

In a 2019 paper in Neurology, Anna Elisabetta Vaudano and her colleagues report that young people with narcolepsy have a broader pattern of metabolic activity lighting up the brain when they laugh, but do not experience cataplexy. For example, the motor cortex, the part of the cortex responsible for controlling voluntary movement, is activated more than in healthy controls.

I asked Vaudano whether this finding means that these young people were trying to exert deliberate control over their cataplexy events – sort of like sensing and holding back a sneeze, but something more powerful.

The answer is not straightforward, she said. Interviewing people with narcolepsy reveals that some can use "tricks" to avoid cataplexy – thinking of something else or tensing their muscles, but the Bologna team was asking their young subjects to just let it happen. In their paper, the authors speculate that their study participants –newly diagnosed and unmedicated – are adopting “precocious, unconscious strategies to inhibit cataplexy occurrence.”

Vaudano pointed out that one region of the brain called the zona incerta (meaning “zone of uncertainty”) was only activated during laughter in people with narcolepsy, not in controls. Research on the zona incerta in animals suggests that it also helps to control fear-associated behavior

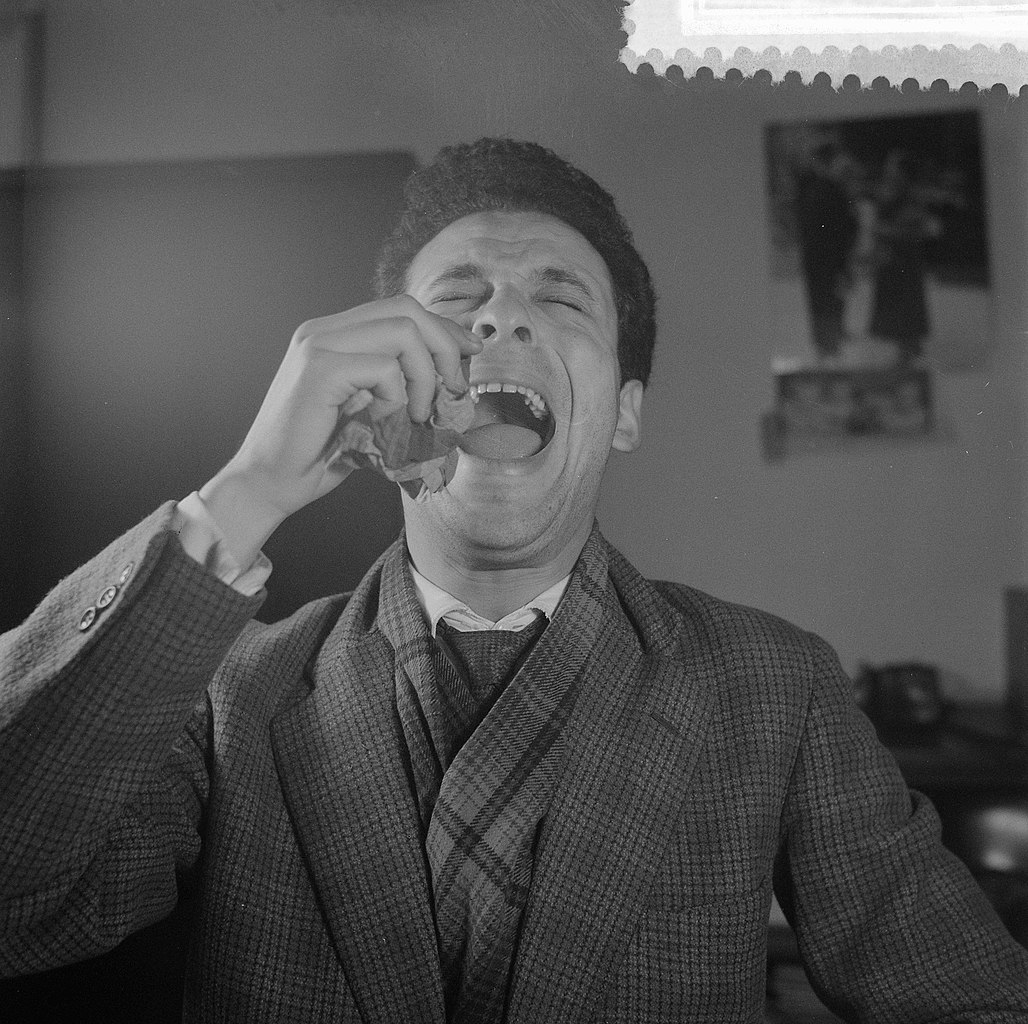

Like sensing and holding back a sneeze

Harry Pot from Wikimedia Commons

Even when they don’t experience cataplexy, it appears that people with narcolepsy respond differently to humor. In another recent paper published in Sleep, Norwegian researchers asked people with narcolepsy and their healthy relatives to watch movie clips that included a joke punchline, and had study participants rate the movie clips they saw. MRI showed no differences in brain activation between patients and controls for the movies viewers thought were funny. For clips without punchlines, there was also no difference.

Differences only came for movie clips with punchlines that were rated neutral (not funny) by the viewers. For these, people with narcolepsy showed more brain activation, compared to controls, in several regions connected with emotional processing and REM sleep. Some parts of the brains of the people with narcolepsy reacted as if the movies were funny, even though they said they didn't find the clips funny. Study leader Stine Knudsen said this phenomenon may reflect being on guard, or “hypersensitivity to potential humorous stimuli.”

While humor is known to cause cataplexy, other people with narcolepsy I talked with described incidents brought on by anger, surprise, or disappointment. Each person has their own individual triggers. At a conference I attended, Julie Flygare of Project Sleep, a woman living with narcolepsy with cataplexy, said that she can attend a comedy club without trouble, but had experienced cataplexy when she saw an opossum in her driveway while with a friend.

Opossums do look kinda funny...

Cody Pope on Wikimedia Commons

“For me, cataplexy is often much more likely to be caused by social interaction and communication with people close to me, than by a movie or stand-up comedy club,” she said in an email.

Narcolepsy is known for overwhelming sleepiness, but cataplexy affects the texture of someone's social life. Some people with narcolepsy say that they tend to avoid situations where they feel cataplexy might occur, which can perturb their relationships. An upcoming movie called "Ode to Joy", based on the story of a real person from Oregon, even uses this as a plot point. As Matt O'Neill, from the organization Narcolepsy UK, said: "If I have cataplexy in front of you, it's because I feel comfortable around you, or I really dislike you."

Adults or teenagers with narcolepsy can go for years without a proper diagnosis, and understanding cataplexy better could help doctors make that determination more quickly. In children especially, cataplexy can look different than it does in adults. For children, cataplexy often affects only part of the body, such as the face or arms, or it can appear as disturbed gait or repetitive movements of the fingers or tongue. Cataplexy often changes as a child becomes older, morphing into the form more typical for adults. Medications are available that reduce cataplexy, such as antidepressants, which exert their effects by suppressing REM sleep, as well as an expensive but effective sleep aid called sodium oxybate.