Ryzhkov Sergey via Wikimedia

Invasive species are pushing close to the boundaries of protected areas

Protected areas are successful at maintaining ecosystems, but for how long?

The American mink is a small mammal with soft fur and seemingly charming features. It's also a vicious predator that feeds on small animals including birds, mammals, fish, reptiles, and amphibians. Through the fur trade in the 20th century, it was introduced in most European countries and certain parts of Asia and South America via accidental escape or deliberate introductions. It devastated native wildlife by gravely reducing numbers of birds, frogs, and small rodents.

Invasive species are organisms that are not native to the area where they are found. They affect virtually every country in the world and recently have even made their way into Antarctica. Invasions by alien species threaten local species through predation or by competing for the same habitat and food source. In fact, invasive species are among the top five reasons worldwide for the loss of biodiversity.

Apart from the devastating ecological effects, invasive species also present a huge economic burden to countries. Globally, they cause billions of dollars of damage around the world every year. When invasive species infiltrate protected areas – key instruments of biodiversity conservation – the effects can be exceptionally devastating.

American mink (Neovison vison) was found in 1,251 protected areas such as Cairngorms National Park in the UK, where this photo was taken

Professor Tim Blackburn, UCL

In a recent study published in Nature Communications, researchers led by Xuan Liu from the Chinese Academy of Sciences analyzed where almost 900 species of invasive terrestrial animals lived in relation to almost 200,000 protected areas worldwide (including places like national parks, nature reserves, and other protected landscapes). They found that, so far, over 90% of protected areas are free of invaders.

While this is great news, the study also found that invasive species were found within 10 km of the boundaries of 89% of protected areas, and nearly all of them had an invasive population within 100 km of the borders. More than 95% of all protected areas were deemed suitable for animal invasion. Thus, while we have been doing a great job in protecting ecosystems by keeping invaders out of these areas so far, this success might not hold for long.

Liu and the other researchers also looked at different factors that might influence the likelihood of a protected area being invaded. For each area they analyzed, they looked at, among other things, the size, the year of designation, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) protection status, and the human footprint – meaning the amount of human influence inside the protected area, such as roads and the density of people. Unsurprisingly, they found that bigger protected areas, those with greater human footprints, and that had been established more recently, had more invaders.

Strangely, however, the IUCN protection status did not explain the number of invaders in a protected area. IUCN distinguishes six different categories for protected areas, ranking them from the highest security measures to the lowest. In this study, IUCN category II areas, meaning those with the second strictest security measures including the restriction of visitor numbers and the ban of almost all resource use (such as logging, hunting, and fishing), had the highest number of invaders. Category II areas are national parks which are often large in size. This, together with having many visitors for tourism who can unknowingly carry animal stowaways (for example, insects or small animals hiding in cars) into the parks could explain why they are the most affected. Nonetheless, it seems that the current policies for keeping invasive species out from some of our highest valued protected areas are not as effective as we’d like.

The American mink is one of the sneakiest invasive species, now found in 1,251 protected areas around the world. A single mink can destroy entire colonies of ground-nesting birds, and in the United Kingdom it has entered several national parks and has driven species like the water vole to near extinction. Apart from killing local fauna, the introduced minks have also damaged local mink populations by competing for food and territory. The invasive American minks are even known to be aggressive toward the critically endangered European mink, and potentially kill them.

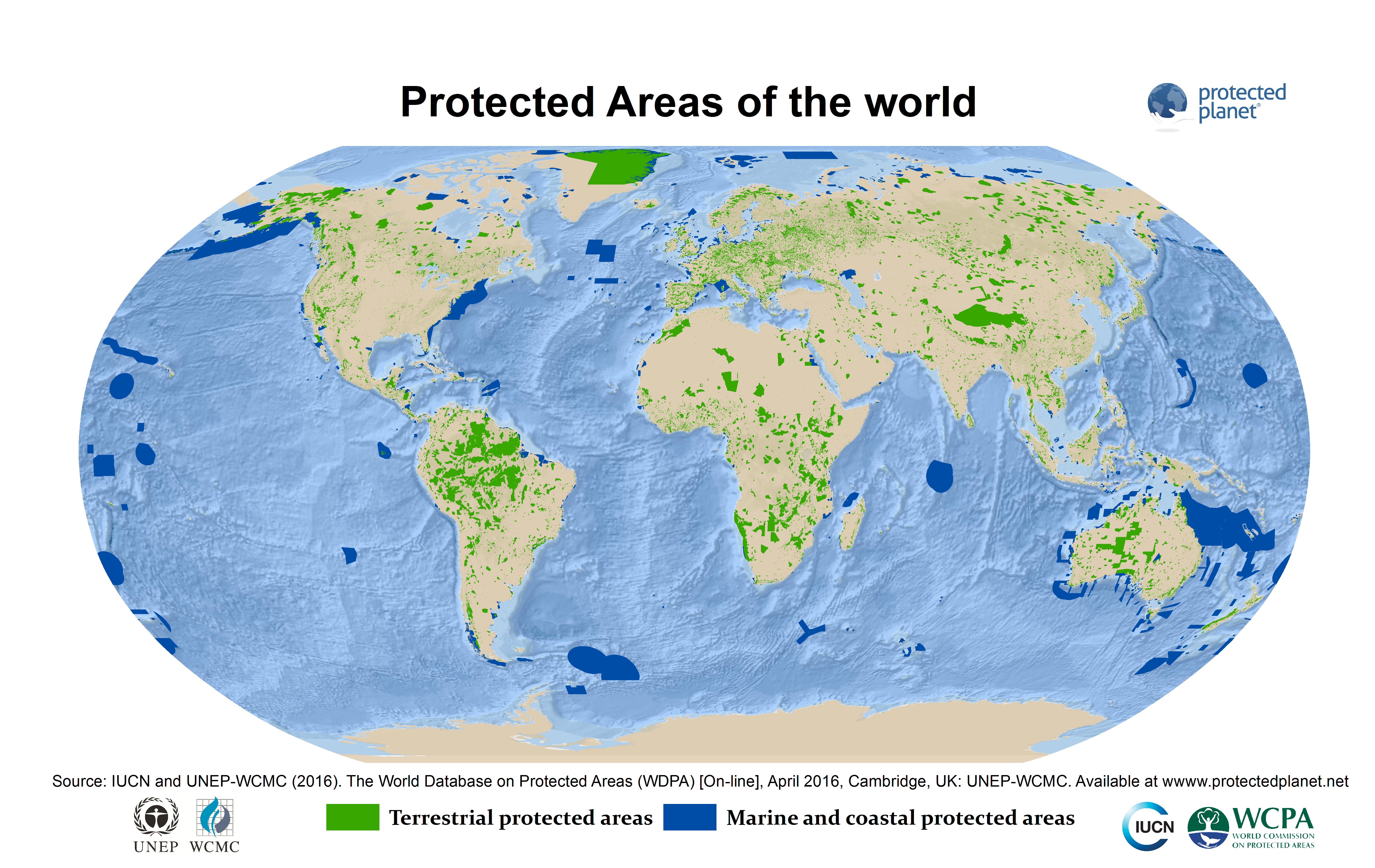

A map of worldwide protected areas, in both terrestrial and marine/coastal regions

Protected Planet/IUCN

By preying on animals from commercial farms such as fish, rabbits, chicken, and sheep, the American mink is also the cause of economic damage. Even these commercial damages though are dwarfed by the cost of trying to eradicate them from the wild to prevent further harm to the environment. Control measures include shooting, snaring, trapping, and hunting down minks with dogs as well as erecting mink-proof fences and using special repellents. In the UK, helping the population recovery of native otters, which are hostile toward minks, has also proved to be a successful intervention.

Liu and his fellow researchers argue that to prevent problems like this in the future, we have to improve the control measures of protected areas. Monitoring vehicles and tourists when they enter parks is a good method to reduce invasion risks, as is regularly monitoring areas for potential invaders. While this will impose some greater costs in the management of protected areas, they would be an insignificant amount compared to the cost of eradication efforts.

In the 21st century, anyone is able to reach the farthest corners of Earth in a matter of days. As the stowaways we carry with us can also do the same, we simply cannot afford to overlook this issue. It is still not too late to act to make sure that protected areas remain protected.

Thanks for covering this fascinating and pressing issue. It is a global concern, and you described it well with global examples. Protected areas are not immune from the harmful effects of invasive species just because they are protected; both preventative and responsive actions need to be taken.

While the publication this article focused on only terrestrial invasive species, we must not overlook the unique suite of challenges presented by marine ecosystems. For readers interested in a marine example, a report suggesting management actions for the Mediterranean can be found here.