MabelAmber on Pixabay

Early diagnosis of Parkinson's is becoming possible, but how early do patients want to know?

Each person's disease journey is different, and an early diagnosis is not necessarily a timely diagnosis

A couple years ago, I was asked to describe my research interests, and, without hesitation, I replied, "Pharmacological fortune-telling." There has always been an appeal in being able to predict the future. But rather than whirling our hands above a crystal ball, scientists known as "disease modelers" use data to predict things like who might develop a disease, what medication they may respond to best, and how their disease will progress.

With some risk factors, people may know if they have a high probability of developing a disease and choose proactive treatment, such as those carrying harmful BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations connected to breast cancer who opt for a mastectomy. With other conditions, however, such as Parkinson's disease, there are no treatments available that can "modify" the disease, meaning slowing down, stopping, or even reversing it.

Parkinson's is a chronic, progressive neurodegenerative disorder associated with the loss of dopamine-producing cells in a part of the brain called the substantia nigra. When 60-80% of these neurons die, people begin to experience 'motor' symptoms, namely tremors (shaking), slowed movement, rigidity, and difficulty with balance. In addition to the motor symptoms, people with Parkinson's also experience numerous non-motor symptoms (not related to movement), including depression, constipation, and problems with learning and memory, some of which can appear years, and even decades, prior to diagnosis. With the loss of that many brain cells at the diagnosis stage, some Parkinson's researchers believe targeting the period before diagnosis, known as "prodromal" Parkinson's, will be key for testing disease-modifying treatments.

A task force convened by the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society (MDS) has now developed updated research criteria for the likelihood of having prodromal Parkinson's (also called pre-Parkinson's). Since it is not possible to truly know if someone has prodromal Parkinson's until they become diagnosed with the disease later on, these research criteria are based on probability that a person with X symptom actually has Parkinson's disease. The model is based on the presence or absence of factors like constipation, anxiety, inability to smell, smoking, and sleep disturbances.

But when people hear these symptoms, they almost always ask, “I get constipated and have anxiety. Does that mean I’ll have Parkinson’s one day?” Well, not quite.

Each of these risk factors in the updated model was assigned a "likelihood ratio" — the likelihood that a certain result would be expected in someone with the condition, compared to the likelihood that it is expected in someone without the condition. For example, males are more likely to develop Parkinson's than females, so male sex was assigned a likelihood ratio of 1.2. Regular pesticide exposure has a likelihood ratio of 1.5, and constipation is 2.5.

Researchers have developed a model for how likely it is that a person has Parkinson's disease, based on their symptoms.

Rawpixel.com on Pexels

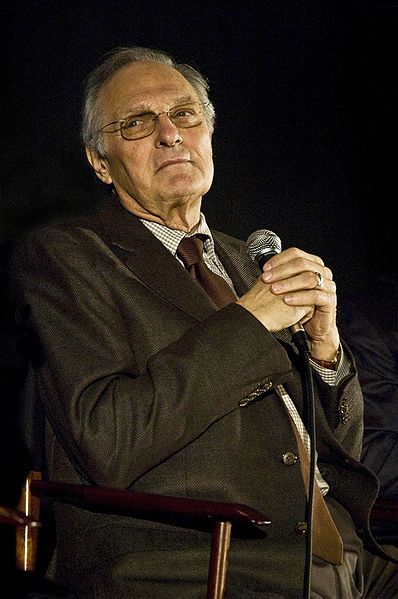

The item with the highest likelihood ratio? Polysomnogram-proven REM Sleep Behavior Disorder, with a likelihood ratio of a whopping 130. During REM sleep, our brains prevent movement, so we do not act out our vivid dreams, but in REM Sleep Behavior Disorder, this process is disrupted. In fact, when actor Alan Alda came out with his Parkinson's diagnosis, he shared he felt he may have Parkinson’s because he threw a pillow at his wife while dreaming about throwing a sack of potatoes.

As scientists better understand Parkinson's and prodromal Parkinson's, the definitions and diagnostic criteria improve, but there is still currently no cure. While no drugs exist that can alter the course of the disease, there are numerous treatments available to provide relief from the motor and non-motor symptoms.

A 2018 article by a group of researchers at University College London and Queen Mary University of London made a differentiation between an early diagnosis and timely diagnosis. A timely diagnosis "is tailored to the individual, their priorities, their social environment, and the therapeutic and health-system options in which they live," the article authors write. And in my own conversations with people who have Parkinson's, the range in responses about whether they would have wanted an earlier diagnosis shows just how personal this decision can be.

What about the post-diagnosis aspects of Parkinson's disease modelers are trying to predict? More modern, "big data" approaches may allow us to identify things we may have not have not known before, like discovering whether the use of certain medications is protective or harmful, or predicting when someone might become unable to live independently. For these outcomes, I have also heard a range of responses. Some want to know how certain conditions they have are affecting their Parkinson's; others do not want to know any of it.

Actor Alan Alda has been open about his Parkinson's diagnosis

These issues are not unique to Parkinson's, as many are seeking to predict similar outcomes in other conditions that currently have no cure such as ALS and Alzheimer's disease. As researchers (myself included) continue the quest to predict various disease-related outcomes, we should keep in mind the people most affected by these conditions, what is meaningful to them, and what guidance and options we can provide that will help them with the daily fight against this disease.

Thanks for writing this article Monica! As your article discusses, the timing of when a patient might want to know about a diagnosis is extremely personal. With the rise of data-driven neuroscience, the ethical dilemma of when to reveal a diagnosis will only become more relevant to our lives. Your article also shows that we need to prioritize talking to patients when putting together policies and guidance, and not just consider their risk scores.