Lab Notes

Short stories and links shared by the scientists in our community

Can we take down the dude wall? Can universities glorify anyone besides white men?

Portrait collections showing only white male scientists send clear signals to anyone who does not fit the mold

Sometimes, barriers to entry in science are invisible, like the lack of confidence felt more routinely by women than men. Other times, it is literally hanging on the walls themselves. The Yale School of Medicine’s flagship building is just one example: of the 55 portraits hanging throughout the building, 52 depict white men and three depict white women.

The impact of these portraits on Yale medical students is the focus of a new study that appears to be the first of its kind. Researchers (also from Yale) conducted interviews with 15 students, the majority of whom were not white men, and organized their responses thematically.

Multiple students said they felt the portraits reflected institutional values of whiteness, maleness and elitism — values they did not share and, as a result, made them feel alienated. If the portraits could speak, “they might spit at me,” one student said. Others noted the literal whitewashing of history by glorifying the subjects in the portraits without acknowledging in some cases their ties to the slave trade.

These results should not shock anyone, but they do underscore the need for administrators to think critically about visual representation in science. Some hospitals and universities are tackling this issue by commissioning works depicting historic figures who made standout contributions to science despite their non-whiteness or maleness (and they certainly do exist). As Akiko Iwasaki, a Yale professor not involved in the study put it so elegantly on Twitter, “Can we take down the #dudewall?”

What do proteins and enzymes sound like? Now we know.

MIT researchers have created entire soundtracks from amino acid sequences with the help of artificial intelligence

Photo by Malte Wingen on Unsplash

Researchers at MIT have just developed an artificial intelligence method to correlate amino acids found in the functional proteins in our bodies to music. They allocated a tone to each amino acid, and when the sequence of amino acids that makes up any given protein is played back, each is a unique musical composition.

This works so well because proteins are structurally complex, made up of hundreds of amino acid units which fold into distinct motifs and shapes that allow them to do their jobs in our cells. Proteins are typically studied by examining amino acid sequences or with 3-D X-ray crystallography - this new work provides a completely new way to study proteins.

One challenge the researchers faced is that conventional musical scales have just 12 notes, but there are 20 amino acids that make up proteins in our bodies. They actually used quantum chemical theories to translate the specific vibrational frequencies of the molecules in the amino acids into sounds, then made these audible to human ears. In addition to the protein "orchestra" linked about, you can listen to another amino acid soundtrack in the MIT press release about this publication.

One very exciting aspect of this method is that it is also possible to do the process in reverse to generate new proteins not found in nature based on small changes made by artificial intelligence to the existing protein soundtracks!

Newly released data shows that 76 billion opiod pills were distributed in just six years

Drug companies have been prioritizing profits over human lives for years

Tbel Abuseridze on Unsplash

Opioid use and abuse has been on the rise in the United States since the late 1990’s, when drug companies began to market opioid products, particularly oxycodone, as safe and effective pain-relievers. This marketing scheme led to a dramatic increase in production and distribution of opioids. Deaths from opioids began to increase dramatically after 2000, and many illegal distribution centers sprang up to meet demand for the drugs. Things have gotten so bad that in 2017 the federal government declared the opioid crisis a public health emergency. Things haven't improved much since then.

Recently, the Washington Post and the Charleston Gazette-Mail teamed up to demand the public release of the Automation of Reports and Consolidated Order System (ARCOS), a database containing information about how the companies produced and distributed opioids. Although only part of the database was released to the public, the information provides a solid overview of the opioid epidemic’s scope and impact. For instance, we now know that a staggering 76 billion pills were distributed around the US between 2006 - 2012. Alarmingly, the information in the database showed that many of the companies manufacturing opioids ignored requirements from the DEA to report suspicious orders, filling them in the hopes of maximizing profits.

What I find particularly striking about this report is the very idea that opioids could be widely used safely. Opioids are, by nature, powerfully addictive drugs, because they stimulate the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine. Did the drug companies not know that people could get addicted to their products before their abuse became a problem? Or did they simply not care?

Hopefully, now that this information is available, policymakers and physicians can use it in response to the opioid crisis. The evidence implicating the companies will also make it easier for plaintiffs to hold them accountable. Unfortunately, the data comes too late for the many victims of the opioid epidemic, which by now has had devastating social and economic costs for them and their families.

The best science stories from around the web, hand-curated and eye-read by science writers

The week's not over yet but it's been pretty good so far

Photo by Raj Eiamworakul on Unsplash

We here at Massive have great taste. Particularly when it comes to science writing. It's our job! These are the stories we've been reading this week that we think you should read too. Imagine this round-up like your favorite cupcake baker taking you around town to all the cupcake shops they love. You all do that too right?

The obsession with colonizing space from many people (especially the ultra rich) has always been baffling to me. Space is big, and dead. It always struck me as a kind of anti-environmentalism, where we can solve all the problems we've made here on Earth by just packing up and leaving. It isn't happening. -DS

Dying from heatstroke seems like something that can only happen to extreme athletes or particularly unlucky folks. This article (the partner to Outside's piece on what it's like to die of hypothermia) dispels that myth. Human physiology piled onto mildly questionable choices - that certainly wouldn't be deadly in other circumstances - can easily result in a very dangerous situation for anyone spending time outdoors in the summer sun. Read this article as a reminder to keep yourself and your loved ones safe on your next hike or beach day. - CF

Algae's kind of gross but harmless as long as you’re not a kid or a dog and don’t swim in it. Also PSA, don’t let your dog eat algae chips: “It’ll get all crunchy like potato chips, and the dogs love to eat that.” - GSM

No explanation necessary. -DS

Caregiving is increasingly falling to young people, especially minority millenials

Employers and government have a responsibility to help ease the burden for those caring for loved ones with dementia

Photo by Cristian Newman on Unsplash

With Alzheimer’s disease expected to impact 16 million individuals in the US by 2050, younger generations will increasingly assume caregiving responsibilities. More than a third of today’s caregivers are employed full-time. As millennials take on more and more informal caregiving responsibilities, public and workplace policies must consider financial assistance or other support (e.g., family leave or allocated time off).

More than half of millennial caregivers are minorities and are more likely than any other generation to balance caregiving with employment. Latinx millennials work more hours each week, on average, and spend more time providing care than young adults of other backgrounds. This is partly because Latino culture is built around families and they are, therefore, more likely to live in multigenerational households.

With these challenges come opportunities to promote policies that enable active engagement and quality of life for millennial caregivers who are ethnoculturally diverse. Both the public and private sectors must collaborate to create culturally sensitive resources and implement innovative strategies affecting the millennial caregiving experience. While by no means exhaustive, the list below provides some ideas that could lead to a substantial impact.

Health Effects: Better training for informal caregivers to understand the signs of dementia (and specifically Alzheimer's disease) and the family caregiving experience. This can help identify and tackle stressors to reduce caregiver burnout and depression.

Financial Well-being: Permitting Medicare Advantage plans to offer a respite care benefit as a distinct and optional benefit. Medicare currently covers respite as a part of its hospice benefit, but the beneficiary qualifications are more appropriate for patients who are terminally ill.

Employee Productivity: Supporting caregivers through flexible work policies, including offering paid or unpaid caregiving leave beyond the requirements of the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA). This is a promising but still emerging trend that has been shown to boost an employer’s competitive advantage in recruitment and retention. Currently, FMLA covers only 55 to 60% of workers due to limitations on eligibility. For instance, employees must have worked for their current employer for at least 12 months.

As the burden of dementia increases in the US, it may also be worth looking toward Japan - a country where 27% of the population is over 65 years old - for the "dos and don'ts" of how to create effective public policies and social space for those affected and their caregivers.

New parasitic interaction discovered in Antarctic lakes

We still understand very little about life in Earth's most extreme environments

When most people think of “parasites”, they imagine malaria, tapeworms, and the mind-controlling Toxoplasma gondii.

But researchers from the University of New South Wales in Australia have observed a new parasitic interaction in salty Antarctic lakes. The study has enhanced our understanding of how some organisms acquire nutrients and survive in freezing cold environments.

The researchers collected water from two different lakes in Antarctica and found that it contained a large amount of archaebacteria, which are highly resilient organisms that inhabit some of the world’s most extreme environments. They found especially high numbers of two species called Nanohaloarchaeum antarcticus and Halorubrum lacusprofundi.

Previously believed to be ‘free-living’ organisms, the Nanohaloarchaea are actually unable to survive on their own. Instead, they acquire essential nutrients by poking holes in H. lacusprofundi cells, sucking out their cytoplasmic “juices”, and feasting on their gooey insides. Yum!

We still have a lot to learn about how microorganisms survive in extreme environments, as evidenced by this fascinating discovery.

Planting trees is great, but it's not a silver bullet for stopping climate change

Although new research finds that huge areas of the earth could be reforested, this will not let us off the hook for reducing emissions

Photo by Pedro Kümmel on Unsplash

As a growing number of world governments declare climate emergencies and cities around the world experience record-smashing deadly heatwaves, more thought is being given to concrete actions that will limit global warming and avert the transformation of our planet into a “hothouse” state. In addition to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, it will likely be necessary to invest in carbon capture – reducing the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by storing the carbon in other forms. Photosynthetic organisms naturally convert atmospheric carbon dioxide into biomass as they grow, so one straightforward strategy is to increase forest cover.

A recent study published in Science analyzed satellite photographs of the Earth and determined that our planet could theoretically support just under a billion new hectares of forest cover without impinging on existing urban and agricultural land, potentially enough to allow us to meet climate goals. However, this estimate assumes current environmental conditions, and the actual potential forest cover could be much lower due to climate change itself.

While a global reforestation effort would likely require international collaboration, over half of the estimated potential forest is in one of six countries: Russia, the United States, Canada, Australia, Brazil, or China. Tree planting is considered the cheapest and simplest solution to climate change, but it will certainly have to be mixed with emission reduction and other carbon capture strategies to represent a clear path forward.

Meet Eunice Foote, early climate scientist and women's rights leader

Her experiments uncovered the greenhouse effect three years before the man who was widely credited with this discovery

In the spirit of Massive's "Science Heroes" theme, I present Eunice Newton Foote, an early climate scientist and leader of women's rights. Since July 17 would have been her 200th birthday, here are a few facts about the woman who demonstrated the greenhouse effect and predicted its effect in the geologic past before John Tyndall, who is commonly credited with that accomplishment.

1. Foote was one of the committee members for the Seneca Falls Convention for women's rights, and was one of the signers of the Declaration of Sentiments.

2. Foote's research on carbon dioxide and water vapor's effects on temperature were published in 1856, three years prior to Tyndall's work on the greenhouse effect (which did not credit her experiments or publication).

3. Having attended Troy Female Seminary and taken basic science courses at a nearby college, Foote then carried out her experiments not at a university, but in a lab at her home.

4. Foote's work was presented at the American Association for the Advancement of Science by a male colleague, although it's debated whether this was because women were not permitted to present work, or for other reasons.

5. Her research was later published under her own name. Foote was an AAAS member, but the organization did not grant women the title of 'Fellow.'

Although little is known about Foote following the Convention, and the 1856 publication appears to be her only paper, she now stands as more than a Foote-note in time.

The unknowns of US immigration policy are increasing anxiety among first-generation Latinx teens

More studies on the long-term health consequences of these policies on immigrant families are urgently needed

Photo by Nitish Meena on Unsplash

Despite the fast-moving news cycle nowadays, shifting immigration policies and policy guidelines make headlines every week. At the end of one dizzying week that included a serious discussion on the decriminalization of border crossings and a Supreme Court ruling against adding a citizenship question on the 2020 U.S. Census, the Supreme Court announced it would hear the Trump administration’s appeal to end Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) next fall, just in time to issue their ruling the summer before the election. And that was just one week in June.

Dreamers have faced uncertainty about their immigration status since September 2017 when the Trump administration moved to terminate the program and the federal courts took up several lawsuits challenging these actions. Now, new research shows that immigration policy concerns are taking mental tolls on first-generation Latinx (Latino/Latina) adolescents.

Using data from a long-term study of primarily Mexican families living in California’s Salinas Valley region, researchers surveyed 397 sixteen-year-olds with at least one immigrant parent. In the year following the 2016 presidential election, nearly half of the teens reported that they worried about how immigration policies could affect themselves and their families. Compared to before the 2016 election, the teens who worried more about immigration policy also reported an increase in symptoms of anxiety. Particularly among teenage boys, higher anxiety was correlated with poor sleep quality.

As we debate changes to U.S. immigration policy, many immigrant families are having difficult conversations about planning for the worst-case scenario. This research shows that the uncertainty regarding immigration status has effects on mental health in children as well as adults. More studies need to be done to address the long-term health consequences of these policies on immigrant families, both directly and indirectly through their access to healthcare services.

Fighting cancer with exploding antibody-filled bacteria

A new study finds that these juiced-up microbes can shrink tumors in mice

Researchers at Columbia University have engineered bacteria to dive into tumors and explode, releasing a tiny antibody. The study, published in Nature Medicine, is part of a larger trend in synthetic biology, a field of research that aims to genetically modify living organisms for human benefit.

In the study, E. coli, a microbe that normally resides in the human gut, was engineered to create and release the therapeutic nanobody inside of tumors. The team tested their “cancer-killing” microbe in mice with B-cell lymphoma and observed that tumors injected with the engineered microbes rapidly shrank.

But this isn't the coolest part of the study.

The mice had tumors in both of their legs, but when just one of their legs was injected with the programmed bacteria, both tumors began to shrink. This observation supports an old idea in cancer biology called the abscopal effect. The hypothesis underlying this effect posits that that untreated tumors will shrink when a different tumor is treated due to peripheral actions by the immune system.

While these engineered microbes will not be used in hospitals any time soon, this study offers an intriguing glimpse into the amazing, ongoing interactions between the immune system, bacteria, and metastatic cancer.

Silver-haired bats wake up, re-heat their bodies, and flee when attacked

They can warm themselves up faster than any other mammal, increasing the odds that they escape incoming predators

Imagine waking up in a panic from a deep sleep in response to a predator in the area. Now imagine doing that but having to rewarm your body temperature back to a normal level in order to flee or fight off the predator. This is exactly what silver-haired bats (Lasionycteris noctivagans) do, and surprisingly they are able to do it the quickest out of any mammal measured to date.

To figure this out, I and other researchers at the University of Winnipeg measured body temperature changes in response to an acute stress in three different situations. The first was during the night as the bats were out searching for food, the second was under normal resting conditions during the day, and the third was during the day when the bats were cold (torpid). In all cases, we measured body temperatures immediately, then measured them again after five minutes of handling. The handling induced the same stress response the bats would have when accosted by a predator.

Surprisingly, we found that bats feeding in the night decrease their body temperature in response to handling, potentially to avoid overheating. Bats resting during the day increased body temperatures moderately, as expected. Very surprisingly, however, body temperatures increased extremely quickly when they were cold. This quick response in body temperature change may reflect this species' ability to deal with predators and people.

Your salad might bring an unwanted guest to the dinner table

A new study finds that bagged and canned produce can occasionally (but rarely) come with a side of frog, lizard, bird, or rodent

As I was perusing Twitter the other day, a story from Vice titled, "Your Bagged Salad is Full of Frogs," caught my eye. The piece opens with the tale of a California woman who found a little frog in her salad bowl. She (understandably) freaked out, but in a heartwarming twist, she and her husband cleaned the little guy off and built him a terrarium so he can live out his days with them in their home. They dubbed the frog "Lucky."

This story is just one in a newly published dataset of the prevalence of vertebrates in produce sold in the U.S. between 2003-2018. The research, led by Daniel Hughes of the University of Illinois and published this month in Science of the Total Environment, is unique in that it uses online media reports of cases like Lucky's to explore how human-wildlife conflict in our agricultural systems can impact food safety.

Unpleasant as it sounds, bagged salads can include surprise guests like frogs, rodents, and snakes. Check your food before you eat it!

Agricultural fields may appear monotonous from our point of view, but they're still habitat for wild animals like frogs, lizards, and rodents. Harvesting is now mostly automated, which is highly efficient but also means that there is no human being watching out for small animals that might be scooped up in the process. Rarely, these animals can make it into our food. To figure out just how common this is, Hughes searched the web and logged all stories he found with keywords like "frog," "mouse," "snake," "fish," bird" combined with produce items like "salad," "lettuce," "mixed greens," and "vegetable."

The search turned up 40 cases of animals or animal parts in produce products between 2003-2018. These included 21 amphibians (frogs and toads), nine reptiles (lizards and snakes), seven mammals (mostly rodents, with one bat) and three birds. Nearly 75% of these were in conventional produce, as opposed to organic, which was the opposite of what Hughes expected, and the majority of cases were found in bagged produce.

This is gross and shocking, but it's important to keep these 40 cases in perspective: Americans eat 11 pounds of green/red leaf and Romaine lettuce per person per year, and so a very, very small percentage of bagged salads come complete with an animal surprise. Even so, it is a good idea to thoroughly check produce for unwanted hangers-on before you eat it. Who knows - you might even end up with a new pet!

An influx of smelly seaweed is deadly for marine animals in the Caribbean

The explosion of Sargassum is bad for coastal ecosystems and tourism

hat3m on Pixabay

The next time you vacation to a Caribbean beach like Cancún, you might be greeted with a smell of rotten eggs! Since 2011, blooms of a brown seaweed called Sargassum have been piling and decomposing on the Caribbean beaches where they make landfall. Decomposing algae remove oxygen from the water, killing marine life and affecting the businesses that depend on those beaches.

But how much marine death has been caused by the massive influxes of Sargassum? A team of researchers in the Yucatán region of México recently published an article in the Marine Pollution Bulletin that quantifies the mortality of marine life from 2018’s Sargassum bloom season. They counted the number of marine animals that had washed up on the east coast of the Yucatán, which includes popular tourist spots Puerto Morelos and Cancún. They also collected water samples to assess the water quality in the affected areas.

The dead animals they found comprised 78 species. Over half were fish (59%), followed by crustaceans (28%) many of which came from shallow coral reef habitats close to the seaweed-strewn beaches. They also found that water quality was poor, with low-oxygen conditions and increased ammonium and hydrogen sulfide in the water. Conditions like that combined with the high amount of toxins have made a perfect storm of massive mortality from a decomposing seaweed.

Managing the Sargassum in those coastal areas will be of utmost importance, as these heavy influxes of Sargassum will affect the local coastal environment and the economies that depend on those areas.

Measuring the health of huge ecosystems is possible with the help of tiny ants

A new study on ant communities in restored ecosystems underscores the importance of keeping forests and grasslands intact

Photo by Sian Cooper on Unsplash

Measuring the health of an entire ecosystem is a huge task. Often scientists look at one group of animals or plants as a metric of how well an ecosystem is working, and one good proxy is ant communities. The diversity of ant species in an area can indicate how suitable an ecosystem is for these tiny workers - who perform important ecological roles, from dispersing seeds to breaking down wood and returning the nutrients to the soil - as well as how amenable that place is for as their larger mammalian, reptilian, and plant counterparts.

Aside from performing so many ecological roles, ants are also relatively easy to survey (see the video below for an example of how researchers study ants) making them an ideal proxy for the success of ecological restoration like reforestation. Compared to natural regeneration, or leaving an area to recover from some disturbance on its own, active restoration requires some investment of time, money, and resources. Active restoration can be worth the extra input if it accelerates or increases the recovery of disturbed places, so measuring its effects on the ant community under different conditions can help us better repair the damage we (or natural forces like hurricanes and fires) have caused to ecosystems.

In March of this year, researchers at the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, published a paper that looked at previous studies done on ant communities in restoration projects around the world. They evaluated the differences in the number of ant species and functional groups (groups of ant species that have similar characteristics) between restored areas and similar undisturbed areas. Measuring both the number of species and number of functional groups present in an area is important because when multiple species perform the same ecological roles, an ecosystem is more resilient to environmental change. Selected studies included temperate and tropical ecosystems, former mines and pastures, and different restoration ages, allowing the researchers to gauge recovery speed and test for effects of land use history and ecosystem type on the ant communities.

Overall, ant communities in restored ecosystems appear to regain functional richness more quickly than species richness, implying low resilience in these areas. This does not mean that restoration is ineffective, but rather underscores the fragility of recovering ecosystems and the importance of preventing disturbance when possible. Restoration ecologists and practitioners might also improve restoration success by facilitating the recovery of species diversity.

Scientists have discovered how to slow the process that creates drug-resistant cancer

Blocking the path of tumor evolution improves treatment outcomes

Drug resistance is a huge problem. Developing a cancer drug is one thing but when a patient’s cancer changes while taking that medication, it knocks treatment back to square one. In fact, recurring cancers with a different genetic make-up to the original tumors cause the vast majority of cancer fatalities. Researchers are now trying to target the mechanisms that cause these changes in cancer cells so patients can remain on the medication that was working for them. Scientists have now successfully identified how to slow a process in our body called mutagenic translesion synthesis (MTS) which contributes to drug resistance.

They found out MTS is triggered by the action of an enzyme called PEV1-POLζ and then designed a drug molecule that fits into that enzyme to stop the process in its tracks. The drug, which they call JH-RE-06, was added to several different cancer cell samples along with different cancer medicines before investigating the drug’s action in mice. It seems to improve how sensitively tumors respond to some cancer medicines and slows tumor growth, which increases the survival rate of the mice. This discovery is a promising step towards reducing the incidence of drug resistance in a few types of cancer. Hopefully in the future scientists will be able to predict how some cancers typically change over time and use these corrective drugs like JH-RE-06 to prevent patients having to change medication.

How a pair of rude gut germs perfectly summarize our war against superbugs

One overstays its welcome, and the other shows up unannounced to ruin the party

NIAID / Flickr

Last month, the FDA reported that two patients fell ill after receiving fecal transplants contaminated with a drug-resistant bacteria. One patient died. We know how this happened, and perhaps how it could have been prevented. This unique case, tragic as it is, also encapsulates our losing battle against drug-resistant bacteria.

Before the transplant, the patients were suffering from an infection of Clostridium difficile, a rod-shaped bacteria that simply can’t take a hint. When doctors prescribe typical antibiotics, a lot of C. difficile's fellow gut germs take that as a sign of "last call," and head home. Like an impolite guest, however, C. difficile doesn’t respond to social cues. Instead, it sees all the extra space and makes itself at home, feasts on your leftovers, and causes uncontrollable diarrhea.

Experts view antibiotic overuse as a leading factor in the continued rise of C. difficile and other superbugs. Once infected, these people encountered a second element to this ongoing war: antibiotic futility. Only a few antibiotics seem to work against C. difficile and patients still likely to relapse. Just when you think C. difficile is getting up from your couch and putting on its coat to leave, it asks for some clean sheets and a copy of your lease.

At this point, resigned, you might decide to invite your polite friends back over, to balance the vibe back out and restore the balance of "good" bacteria in your intestines. That’s why many patients turn to fecal microbiota transplants, or FMT.

Unfortunately, that’s where things went wrong in this case. The trial researchers did not screen for superbugs. Diagnosing and detecting some drug-resistant bacteria is possible, but it takes several days. And that inability to detect specific types of superbugs quickly makes the problem worse. Doctors end up prescribing antibiotics that won't work, which makes people sicker and allows the drug-resistant bacteria more time to evolve. In fact, the NIH has a $20 million competition going on for this very specific research area "seeking innovative, rapid point-of-care laboratory diagnostic tests to combat the development and spread of drug resistant bacteria."

The war against superbugs is being fought in three main battlegrounds: stopping antibiotic overuse, finding more effective antibiotics, and addressing the clinical need for rapid diagnostics. The clock is ticking, and hopefully there will be new breakthroughs soon.

What the “millennials are growing horns” story can teach us about scientific literacy

Consortium member Maddie Bender on how to decipher scientific findings that seem too weird to be true

Photo by David Larivière on Unsplash

Several weeks ago, the BBC and The Washington Post (among other outlets) reported on a 2018 study that seemed to imply that mobile phone use was causing “horns” to grow out of millennials’ heads. The problem? Well, the study was rife with issues, summarized well by PBS NewsHour science producer Nsikan Akpan in an article and on Twitter. Reporters, scientists and science readers alike should be worried about falling into this trap again. Here’s a quick checklist we can all use to improve our scientific literacy:

•Read the whole study: The abstract is often the easiest part of a paper to understand, but it’s also where the authors put the most spin on their findings. The methods and results sections will give a more complete picture of the study.

•Think critically about the sample: Sample size is typically disclosed in the introduction or methods section and is presented as a number (n = sample size). Do a quick gut check to make sure the number doesn’t seem too small, then look at what types of people or other sampling units were studied. In the bone spurs study, for example, all participants had gone to a chiropractor’s office for help, meaning that the sample wasn’t representative of a general population. It didn't include people who don't need a chiropractor.

•Learn some basic stats: P-hacking is a real concern. It’s helpful to know a bit about the statistical tests behind a “significant” result.

•Do a quick Google search on the authors: A Nobel laureate? A disgraced researcher? A chiropractor with a business selling posture pillows? You won’t know until you Google.

•Get an expert opinion: Be aware of when you’re out of your depth, and ask for help! The authors of similar studies, or members of 500 Women Scientists are great places to start.

Self-replicating Asian longhorned ticks have arrived

Climate change is the likely culprit of this new threat to livestock (and possibly humans)

Five cows in Surry County, North Carolina, were recently reported dead after acute anemia attributed to tick infestation. As reported by North Carolina State Veterinarian Doug Meckes, one of the deceased bulls had more than 1,000 ticks on its body. These ticks were identified to be the invasive Asian longhorned ticks, which are newcomers to the United States - they first appeared in 2017.

While the ticks are known to carry human pathogens in their native environments in East Asia, there has been only one documented case of a human bite associated with the Asian longhorned tick in the U.S., which did not cause disease in the patient. In the meantime, there is no doubt that these ticks pose a risk to cattle and other livestock in North America.

These concerns are further exacerbated by the striking fact that the strain can reproduce asexually. This means that female ticks are capable of laying eggs without mating, allowing tick populations to grow and expand rapidly.

But why is this happening?

One of the most likely reasons is climate change. The Asian longhorned tick is not the first invasive species to establish itself out of its ecological habitat, and it unfortunately won't be the last as global temperatures rise.

The increase of invasive, disease-carrying ticks is a global health concern that requires a structured plan of action. However, on the individual level, every person engaging in prolonged outdoor activity is advised to be vigilant, wear protective clothing, and periodically check for tick attachment.

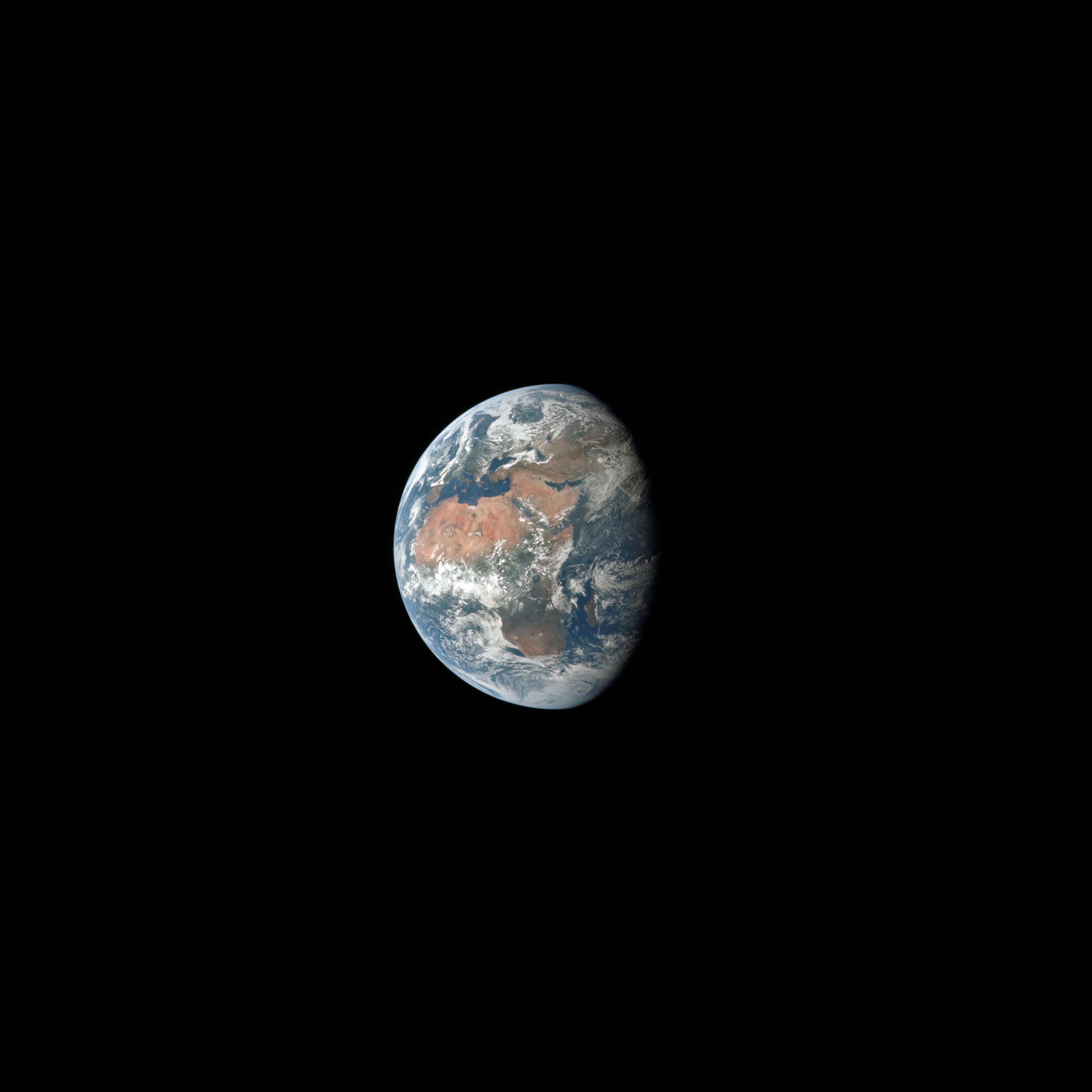

Apollo 11 changed the world forever

Working together, there's no reason we can't change it again

NASA/Michael Collins (id as11-44-6626)

50 years ago today, millions watched grainy images of Neil Armstrong descend down the ladder of the lunar module. With a final push, Armstrong fell to the surface of the moon, becoming the first human to walk on the Moon, and uttered those famous words, “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

NASA/Michael Collins (id as11-44-6667)

While the moon walks are the first things to come to mind when recalling the Apollo missions, their impact extended beyond the moon. The Apollo missions created a need for technologies that revolutionized our world, which eventually led to the device you are using to read this article. The missions also produced stunning images of our planet, leading to environmental movements and conservation efforts to protect our only home. Perhaps most importantly, the Apollo missions were a springboard for our other explorations, including landing multiple rovers on Mars, landing a probe on a comet, sending a probe to Pluto, and even sending the Voyagers into interstellar space.

NASA/Michael Collins (id as11-36-5355)

As we reflect on the historic achievements of the Apollo program, we must remember that it all started with a vision and broad support from public and private entities. In order to tackle the problems of our age, we must adopt a similar strategy. Just as reversing climate change may seem impossible today, landing a man on the moon was once seen as impossible. And yet, 50 years ago today, we did just that.

Would you trust an artificially intelligent doctor?

AI is reading CT scans to more efficiently detect bone fractures in osteoporosis patients

CT scans enable doctors to see 3-D X-ray images of inside the body. Now, artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms are successfully reading CT scans to spot bones at risk of breaking – even if the scan was originally taken to look for something completely different.

Spine fractures are a symptom of osteoporosis, a condition that makes bones more fragile and likely to break. Often, patients with this disease can suffer fractures without even noticing. However, it’s important to spot them and begin treatment as early as possible, before they lead to bigger issues and more broken bones.

Nurses in Oxford, United Kingdom recently used the Zebra Imaging Analytics Engine to re-analyze the CT scans of nearly 5000 patients. They were all classified as either positive (signs of fracture) or negative (no fracture). The nurses verified each result and found that the AI didn’t miss a single fracture. It did err on the side of caution though – about 30% of the scans that were reported as positive by AI were actually nothing to worry about. A similar study has also recently been done by researchers at Dartmouth College.

Overall, the software saves a lot of time for the nurses, as they can now just review the positive scans instead of studying every scan in detail. It has helped identify over 100 patients with previously undetected fractures. Thanks to AI, these people have been able to receive early treatment for osteoporosis, protecting them against broken bones caused by the disease.

The #BetterPoster debate rages – should you redesign your presentations?

Biologist Lauren McKee chooses to reserve judgement – for now

There are two ways that we share our scientific findings at conferences: We give oral presentations and we make posters where we illustrate our questions, methods, and results. The poster is a great opportunity to be creative and show off your work in visually interesting ways. But not all of us researchers are good with – or have time to dedicate to – “the creative stuff," rendering many posters just ugly walls of text. That's not very enticing for conference attendees, especially in a hall of 200 posters.

But psychology PhD student Mike Morrison at Michigan State University recently caused a stir on science Twitter when he unveiled his #BetterPoster. He proposed a radically different design for scientific posters, and made a Youtube video to explain his idea. The new layout has big friendly letters in the middle that broadcast the main message. Along one side are small supportive figures. The design is bright and uses negative space to draw the eye.

It turns out that #ScienceTwitter has opinions about this new design. Some researchers think it will revolutionize the poster session, letting us visit more posters in a session by helping us find the ones we should really see. This is certainly the stance that NPR took in their coverage of the debate. Others were up in arms about the lack of actual information on Poster 2.0, with some even calling it anti-scientific to make a poster Tweetable but not very informative. And some had a lot of fun taking the design to extremes.

I totally agree that Mike's #BetterPoster has visual appeal, and that showing one big central message could make it easier to find the posters I really need to see – although perhaps not, if everyone starts using this new format. On the other hand, most of the time when we make posters it’s because we want to show our work to other experts, who will expect to see the data that we have to back up our big flashy claims. I’ll reserve judgement until I see a Poster 2.0 in the real world.

Apollo 11 was just one space achievement of many in 1969

There was the Crab Nebula, Apollo 12, and more

NASA and ESA; Acknowledgment: J. Hester (ASU) and M. Weisskopf (NASA/MSFC)

Apollo 11 was the biggest news story of July 20th, 1969. But, the whole year was a bumper crop of mind-blowing space discoveries. One of the better summaries of the year, oddly, is Richard Nixon's January 1970 report to Congress summarizing them. Nixon's image in my mind as a cold, paranoid man is hilarious to square with the sunny tone of the report.

Nevertheless it's a great document filled with outstanding bits of trivia. Nixon happily reports that Apollo 11 successfully landed four and a half minutes ahead of schedule, and splashed into the ocean upon return from the moon 41 seconds earlier than planned.

Nixon also described the Crab Pulsar (pictured above), a neuron star in the Crab Nebula. The pulsar was first detected in November 1968 but confirmed in January 1969. Nixon writes (emphasis mine):

"Space astronomy has made major advances in 1969. Observations of the Sun and other stars are being made in wavelength regions that are inaccessible to astronomers using Earth-based instruments. For example, ballon- and rocket-borne instruments have discovered that the pulsar in the Crab Nebula emits powerful X-ray pulses. Each pulse contains as much energy as could be produced by collecting the entire electrical output of our present terrestrial civilization for 10 million years, but this pulsar produces such an X-ray pulse 30 times each second. The study of such extraordinary extraterrestrial phenomena will lead to a new understanding of physical processes that may help us to improve life on Earth."

To illustrate how cool the Crab Pulsar is, here's a time lapse photograph of it:

Pulses from the pulsar (the bright dot just below the center of the picture) ripple through the Crab Nebula.

NASA and ESA; Acknowledgment: J. Hester (Arizona State University)

The president reported on the three other crewed spaceflights that year, Apollo 9, 10, and 12:

"Apollo 11 was one of four successful manned Apollo flights during the year. Others were Apollo 9, during which a manned LM [lunar module] was first tested in space; Apollo 10, in which an LM carried two astronauts to within 47,000 feet of the lunar surface; and Apollo 12, the second Moon landing mission, which was piloted by the astronauts to a precise landing on the lunar surface on November 19, 1969. In subsequent Apollo launches, the astronauts will stay longer on the lunar surface and carry on more extensive investigations."

Don't sleep on Apollo 12. It launched on November 14th, 1969. The second manned mission to the moon worked on the surface for about eight hours (versus just two and a half hours for Apollo 11). They also lost power during the launch after being struck by lightning but were able to get back online within one minute.

The fight for Mauna Kea and the future of science

Native Hawaiian consortium scientist Sara Kahanamoku redefines science in the shadow of Mauna Kea

Photo by Conner Baker on Unsplash

Vigils are once again being held to protest the construction of the world’s largest ground-based telescope on the summit of Mauna Kea, a place of great cultural and cosmological significance to many kanaka ‘ōiwi (native Hawaiians). At face value, these protests may seem like a clash between science and religion. Proponents of the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) claim it will help astronomers explore the universe’s past in order to uncover its origins, while kiaʻi (guardians) advocating for the protection of sacred places are painted as impediments to scientific progress. This false dichotomy glosses over the fundamental issues at stake: who gets to make the decisions for people, for land, for the future?

To me, this debate is not about science vs. culture: in my practice of science, the two are inextricably linked. I am kanaka ‘ōiwi, and I do science because I am Hawaiian. I research out of aloha ‘āina, a deep familial love for the land. My cultural upbringing allows me to walk in the space between Western science and traditional ways of knowing, a duality that enriches the questions I ask and the techniques I use to answer them. I urge supporters of the telescope's construction to employ a similar duality in order to critically examine the colonial history of astronomy in the Hawaiian Islands in the same way that we are beginning to acknowledge other aspects of science’s dark past.

I envision a future where the practice of science is truly ethical: where human rights, including the rights of indigenous people to self-determination, are upheld through the practice of science. I envision a future where scientists value human relationships in the same way that we value critical thinking and curiosity, because I believe that we are all driven to research by aloha—love for people, the natural world, or human knowledge. At this moment, we have an opportunity to change the way that we do science. To me, Mauna Kea is a battle for our future. We scientists can change the course of this debate. We can shape the future to make it equitable, to instill it with aloha.

Apollo 11 brought messages from Earth to the Moon and then almost forgot about them

A gold olive branch, an Apollo 1 commemoration, and messages from world leaders were tossed off the lander's ladder

Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin had a pretty simple task on their to do list when they landed on the Moon: they had to be leave behind a few mementos on the lunar surface. One was a patch commemorating Gus Grissom, Roger Chaffee, and Ed White, the Apollo 1 astronauts who died in an accident. Another was a silicon disk with words of peace from world leaders inscribed on it. Another was a gold olive branch, which according to NASA, "[represented] a fresh wish for peace for all mankind."

They almost left the Moon without leaving the mementos behind. Here's a transcript which doesn't quite do justice to what I imagine the situation looking like in my head:

111:36:38 Armstrong: How about that package out of your sleeve? Get that?

111:36:53 Aldrin: No.

111:36:55 Armstrong: Okay, I'll get it. When I get up there (to the porch). (Pause)

[In his 1973 book Return to Earth - repeated in Men from Earth - Buzz states that, when he was halfway up the ladder - that is, at about 111:26 - Neil reminded him to take care of this task. Clearly, the reminder came a little later than Buzz remembered but, as Journal Contributor Jim Failes notes, "it was a busy EVA".]

[Aldrin - "We had forgotten about this up to this point. And I don't think we really wanted to totally openly talk about what it was. So it was sort of guarded. And I knew what he was talking about..."]

[Armstrong - "About it being on your sleeve."]

111:37:02 Aldrin: Want it now?

111:37:06 Armstrong: Guess so. (Pause)

[From Neil's actions in the TV record, it appears that Buzz has tossed the package down to the surface. It falls to Neil's right. He turns and, apparently, moves it slightly with his foot.]

A replica of the gold olive branch.

NASA, ID: S69-40941

Emphasis is mine. Buzz Aldrin casually tosses a package of absolutely singular, cosmic importance casually out of the lunar lander, Neil Armstrong kinda nudges it with his foot, and they leave.

Cats are like tiny, judgmental camels

Hailing from the desert, cats sneer in the face of heatwaves

Humans, as many of us in the eastern U.S. and Canada learned this week, start feeling uncomfortable when our skin temperature hits 100°F (38 °C), just slightly above our normal core body temperature.

At 38°C, fur and all, your house cat is cool and relaxed, and probably doesn’t even notice it’s much warmer than usual. She won’t even get irritable until her skin hits about 126°F (52°C).

As usual, cats are far superior to people.

It’s a testament to the ancient origins of the house cat. Over 9000 years ago, farmers in a region of the Middle East called the Fertile Crescent entered into a business arrangement with local wildcats that expertly kept pesky mice at bay.

As agriculture grew, and permanent human settlements started to spread, so did their Chief Mousers. Now as many as 600 million cats live as pets worldwide. They haven’t lost their hunting instincts, and certainly haven’t done away with millions of years of adaptation to the desert.

Cats are like tiny, judgmental camels. Owing to their super-efficient kidneys, the “treasure” they bury in the litter box has much less water in it than what we flush down the toilet. Their kidneys are so good that a cat can get all the water they need from a hearty meat-based diet. They can even drink seawater and re-hydrate themselves with no ill effects.

Cats can sweat through tiny glands on the bottom of their paws. They’ll also lick their fur and let the saliva evaporate off to cool down. When all else fails, they’ll even lower themselves to panting like those goofy dogs.

But most pet cats, especially those in the places where air-conditioning is common, rarely resort to these drastic measures.

In a warming world, cats will probably keep their cool.