Produced in partnership with New Harvest

Lab-grown meat could bring about the next agricultural revolution

Cultured meat would require less land, less water and potentially produce less greenhouse gases

There are two major arguments often made in favor of cultured meat: First, it eradicates a tradition of food production that involves animal suffering. Second, it's a more environmentally sound method of producing meat.

In 2011, one of the first studies of its kind found that cultured meat production would have a substantially lower environmental impact than conventional production. This study examined how cultured meat production would impact energy use, greenhouse gas emissions, and land and water use. "Despite high uncertainty," the authors write, "the overall environmental impacts of cultured meat production are substantially lower than those of conventionally produced meat."

Allan Lasser

The researchers estimated these metrics for conventional meat production in three different parts of the world: Spain, California, and Thailand. Because we still lack data on large-scale meat culturing, the researchers projected estimates for required resources based on pilot, small-scale experiments at the University of Amsterdam. They then compared their results with previous data on the environmental impacts of European beef, pork, poultry, and Atlantic salmon production. While the researchers acknowledged their results have a lot of uncertainty, they found that making cultured meat would use less energy than traditional beef, pork, or salmon production (but more than poultry). It would also produce 78 to 96 percent less greenhouse gases, as well as requiring 99 percent less land and as much as 96 percent less water. That's even without considering the huge environmental costs of deforestation associated with animal agriculture (for instance, beef production alone accounts for anywhere from 60 to 70 percent of a country's deforestation, depending on the country). While the study did not consider the impact of transporting animals compared with transporting a cultured product, research from 2015 has shown that the bulk of emissions from the entire American food industry comes from its production—a whopping 83 percent. (Transportation, in contrast, weighs in at just 11 percent.)

The devil, of course, is always in the details; though cultured meat requires less land and water, it does require more energy. That same study published in 2015 found that cultured meat could require both more energy inputs and land than previously suggested. The 2015 study developed an updated computer model of cultured meat production, and compared their results to earlier studies. The results suggest that cultured meat could require more energy than conventional meat production—but agreed lab meat would require less land, less water and potentially produce less greenhouse gases.

Both studies, however, emphasize that much more empirical data on the costs and impacts of cultured meat production is needed. The technology is just too new—and so far only performed at small scales—to make definitive judgments possible.

But while cellular agriculture may offer environmental advantages, these will only become salient if lab meat makes it through some major hurdles: government regulation, further technological development in order to lower costs, and of course, widespread public acceptance. If however, these challenges are overcome, cultured meat could bring almost unimaginable cultural changes.

Meat production worldwide currently takes up about one third of the world's ice-free land. Meat is a major component of cuisine in nearly every human culture. Agriculture employs one in four people in the global workforce (a large proportion of whom are women), and animal rearing and feed production are large parts of this system. These are mind-boggling statistics, and their implications are equally staggering. A future with a cultured meat industry will have to deal with the large-scale disruption in traditional food production, including unemployed farmers, large changes in feedstock production, and significantly altered land management. These are hardly changes that will come about easily.

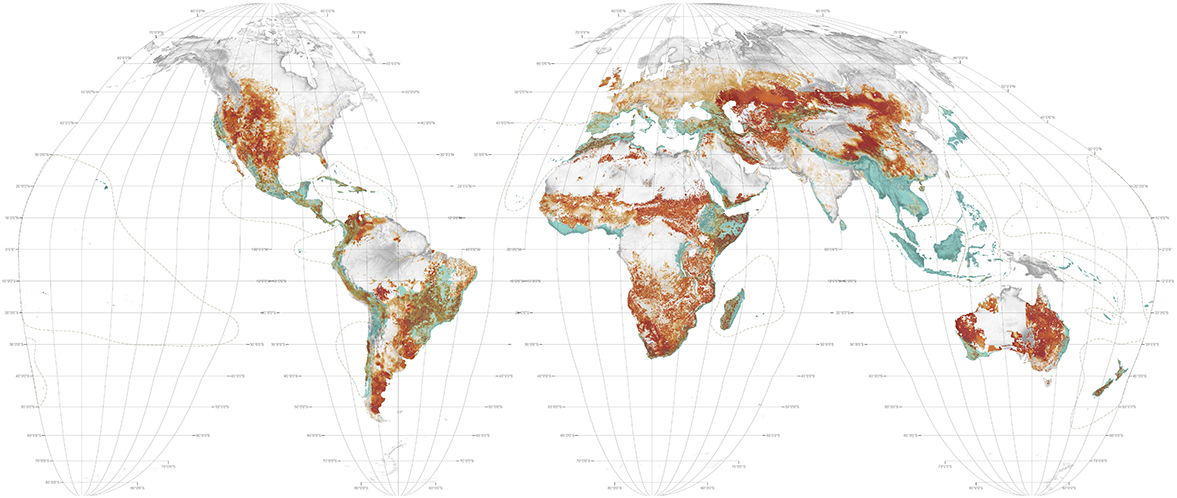

A map of the world's meat production. The darker red color represents grazing land use up to 100% of total land use, while the teal color represents a biodiversity hotspot—a place with high biodiversity that's lost over 70% of its native habitat.

Until now, the evolution of domesticated animals has been closely tied to human societies. Changing this relationship raises important ethical considerations, and right now, there are more questions than answers. What responsibility do humans have to breeds of cattle and poultry whose existence is almost entirely dependent and predicated on agriculture? Conversely, would it be a moral victory to be free of the necessity of killing other animals for our survival? What does such a judgement mean for the morals of the millions of people currently involved in meat production? And do we have the mechanisms to ensure that land freed from animal agriculture is used in an environmentally beneficial manner, rather than being snapped up for more damaging industrial processes?

On the flip side, researchers point out that cultured meat could also lead to more personalized food choices, where nutrient compositions could be tailored to suit individual biological needs. If animal slaughterhouses become replaced by cultured meat, would that result in a general acceptance of animal rights? And will these changes increase or decrease the inequality between the Western and the developing world?