Lab Notes

Short stories and links shared by the scientists in our community

Catch Mercury crossing in front of the Sun, or wait 'til 2032 for your next chance

From about 7:35AM to 1PM EST, a tiny dot will chug across the Sun

Every year there are special astronomical events. This one only happens a handful of times a century. A tiny, tiny, small, smol dot, the planet Mercury, will transit across the Sun the morning of November 11th, like an eclipse in miniature. Look up (with proper eye protection), or wait until 2032 for your next chance to see it. The picture above is of the last transit in 2016 (here's a fun, dramatically-scored video of it, just for fun).

Check out more info from NASA Jet Propulsion Lab here.

By tracking star "pollution," scientists have found exoplanets similar to Earth's structure

Using oxygen pressure as a measure, scientists examined the structural properties of white dwarfs

NASA Goddard

Humans have been wondering whether we truly are alone in the universe for millennia. Part of our quest to understand our place has involved searching for other planets like Earth in the Solar System and beyond — but that's much easier said than done. Space, as it turns out, is big, and other planets are far, far away. Studying them in detail, then, is tricky.

A new study in Science gets around this roadblock by studying white dwarfs, which are not an obscure fantasy reference but are actually the remnants of low and medium mass stars. By studying the "pollution" in these white dwarfs, which occurs when rocky bodies crash into the stars earlier in their lives, Doyle and colleagues were able to estimate the rocks' geochemical and geophysical properties — specifically, what was are they made of and what their structures involve.

To estimate these properties, Doyle and colleagues relied on a key geochemical indicator: oxygen fugacity, which is a measure of the partial pressure of oxygen in rocks as they form. They measured six elements as oxides, including magnesium, silicon, aluminium, calcium and iron. As these oxides must have been in thermodynamic equilibrium with oxygen during formation, their abundances can be used to estimate an overall oxidation state. That estimate can then be linked to atmospheric composition, the geochemistry of its crust and mantle, and even the size of its core.

Ultimately, Doyle and colleagues determined that these rocky exoplanets were similar to Earth and Mars in terms of both composition and structure. So there are some exoplanets like ours in the universe...and this brings us one step closer to knowing how we fit in the universe.

Mice need microbes to forget their fears

Germ-free and antibiotic-treated mice have impaired fear extinction

Image by Alexas_Fotos from Pixabay

Halloween can be a fearful time for many. Ghosts, ghouls and goblins run around on Halloween night, spooking children and adults alike. But once we get used to them and realize that they do not pose a threat, the brain can get rid of, or extinguish, that fear memory. Now that it's November, you've probably forgotten all about any Halloween frights.

Neuroscientists have long been interested in the processes that allow the brain to eliminate fear memories, since problems with "fear extinction" are linked to post-traumatic stress disorder and other anxiety disorders. Now, a new study sheds more light on how the billions of tiny microbes in the body may play an important role in getting rid of fear.

NIH

The "microbiota" encompasses all the microorganisms that live on and in your body. The recent study looks at how getting rid of the microbiota affects fear extinction in mice. The researchers exposed mice to a tone paired with a shock, which after many exposures, leads the mice to create a "fear memory" and freeze in response to the tone. Fear extinction then happens when the mice are repeatedly exposed to the tone without the shock and eventually forget the fear memory. To examine the role the microbiota play in fear extinction, researchers treated adult mice with antibiotics to reduce their microbiota or used mice that had been microbe-free since birth. Although antibiotic-treated and microbe-free mice created a fear memory as well as the control mice, they continued freezing even during extinction, meaning they were not able to get rid of the fear memory.

When researchers looked at the brains of the antibiotic-treated mice, they found that there were significant differences in the expression of genes and of neural activity in the cells of the medial prefrontal cortex, a brain area critical for fear extinction. Among other changes, researchers found that changing the microbiota led to alterations in microglia, the immune cells of the brain. Microglia eat up dendritic spines, which are small protrusions off of neurons that receive input from other neurons. The researchers identified that there was more spine elimination in the antibiotic-treated mice, suggesting that learning might be affected by an imbalance in spine elimination due to microglia alterations.

When researchers analyzed the brain fluid of these mice, they found that there were four chemicals that were decreased in the microbiota-less mice. Researchers think that these chemicals might be an important way that microbes influence brain function. These findings shed new light on the ways that the microbiota can extinguish fear.

TikToks are teaching Generation Z about science

Yes, you can share funny clips on TikTok, but what about communicating science on this platform?

By Afif Kusuma on Unsplash

Teenagers across the world use the short video-sharing app TikTok to escape their schoolwork. Or, that's what teachers thought. Surprise! Creators on the app are now using it to teach Gen Z-ers everything science — ranging from genetics, to squid biology, and even science policy.

TikToks are easily digestible, 15 second videos which are accompanied by a song or audio-clip. The platform is geared towards entertaining middle and high schoolers. Nearly half of users are 10-20 years old, and the average user spends 53 minutes on the app every day. Scientists have spotted a niche in the TikTok market, and are starting to build science communities around the app, such as the Let’s TikTok about Science Twitter account.

What sort of videos have creators made so far? Here are a few examples.

Darrion is a Research Technician at Baylor College of Medicine, and uses a Nicki Minaj meme to explain gene expression:

Sarah McAnulty is a squid biologist and assistant research professor at the University of Connecticut, and in this video, uses Willow Smiths' dulcet tones to soundtrack a sea cucumber.

Megan McCuller specializes in non-molluscan invertebrates at a natural history museum, 1001 jars, and shows something which defies explanation.

Dr. Robert Lepenies is a research scientist in Berlin specializing in policy, environment, ethics, who wants to show other scientists what they are missing.

Reddit's r/science community is one of science writing's biggest outlets, with the stats to prove it

At ASHG 2019, Jennifer (Piper) Below shares the numbers behind r/science's global reach

By Kon Karampelas on Unsplash

When scientists look to sharing their newly published research, they often turn to media outlets with large audiences. But at the American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG) 2019 conference in October, I realized that Reddit's r/science community is the front page we may all be missing out on.

In case you haven't already stumbled on to the site, Reddit – “read and edit” – is a news aggregation social media platform which is often referred to as the front page of the internet. It's composed of over a million subreddits (communities), where the 13-year-old r/science is “a place to share and discuss new scientific research." Fun fact: r/science has over 22.6 million subscribers, making it the fifth largest subreddit on the site.

Jennifer (Piper) Below is an Assistant Professor of at Vanderbilt University Medical Center – and is also one of the 1,500+ moderators on Reddit's r/science community. At ASHG’s communications workshop, Below shared that in September 2019 alone, the r/science community “averaged 5.6 million unique users and 29 million page views” – which happens to be a larger circulation than all top ten US newspapers' weekday circulation (including USA Today, The New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal).

At r/science, Below says that there are three goals: to normalize interactions with scientists, to illuminate the processes of science (rather than only the results) and to promote disintermediation (i.e. skipping news outlets to go straight to the scientists). Below says that r/science does this in three ways: user-submitted links to research, hosting a monthly science discussion series (replacing the old Ask-Me-Anything format) and by verifying users.

As per Below, in September 2019 alone, the r/science community “averaged 5.6 million unique users and 29 million page views” – which happens to be a larger circulation than all top ten US newspapers' weekday circulation (including USA Today, The New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal).

By AbsolutVision on Unsplash

Below says that “presenting your work in an r/science discussion is likely the largest audience you will ever have in your career” and hopes that science discussions on Reddit will become a culturally expected next step for scientists once they publish an “important” paper. For example, r/science has hosted discussion series on climate change, concussion injuries right after the 2019 Super Bowl and a conversation with the research group of Frances Arnold – the 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry winner, where the climate change science discussion had around ten million impressions and over 183k views.

Submissions requirements and comment rules help keep r/science conversations polite and scientific. In fact, by verifying their expertise and displaying an educational flair (e.g. “Grad Student | Physics”), Below says that Reddit users can help provide the context behind research, including methodology and statistics. Of r/science's 5,000+ verified users, 31% have a Bachelor of Science degree, where an additional 4% and 24% identify as professors and graduate students. Biology (19%) is the largest verified field, followed closely by engineering (16%) and medicine (12%). Journalists, writers and university press relations can also request flairs.

Interested in exploring r/science? Below recommends creating a Reddit account – and to consider adding an educational flair to your account or hosting a discussion series. After all, if you truly want to communicate your science with the public, why not head directly to the front page of the internet?

Human disturbance is drying out forests

Thinning out the canopy impacts the water cycle within a forest, causing more moisture to be lost to the atmosphere

New research from northern Michigan shows that when a forest's canopy structure is disturbed — when leaves and branches thin out and provide less coverage — it's not just the view that's affected. The forest's water cycle is affected, too.

Researchers studied two areas of the forest at the University of Michigan's Biological Station. One area had been intentionally disturbed a decade ago by killing certain species of trees to thin out the canopy. One area was an undisturbed control area. Researchers found daily and seasonal differences in the movement of water in these different areas of forest. The strongest differences in water cycling occurred during the summer when evapotranspiration rates were highest. Forest areas with more open canopies showed more mixing between the air above the forest and the air within the forest, suggesting a greater degree of connectivity between the land, forest, and atmosphere. This meant that the air within the forest was drier. Canopy structure, then, serves as a sort of regulating mechanism for moisture release to the atmosphere, with dense treetops holding moisture closer Earth's surface.

Photo by Casey Horner on Unsplash

Water stress is already a substantial problem in many areas of the world, and the problem is likely to get much worse in the coming decades. Since changes to canopies can be driven by both humans (forest management and logging) and climate change (ecological succession), is it important to understand how changes in the canopy structure impact the water cycle in a forest, and, in turn, how this affects regional water stress.

Photo by Wendy Scofield on Unsplash

Ed: All this week Massive is marking Halloween with stories of scary, witchy, and downright ghastly stories from nature.

If you walk around an old cemetery, you might notice tombstones that have sunk into the dirt, tilted to the side, or even appeared to move across the ground since they (and their owners) were first placed. This is because these gravemarkers are heavy and the dirt under our feet is often unstable over long time periods. The tread marks left behind have inspired spooky urban legends.

Unfortunately for those that love ghost stories, there’s a scientific explanation behind the phenomenon of moving tombstones. It’s got the wonderfully spooky name of "downhill creep" (or soil creep), and also explains natural phenomena such as bending trees on a hillside or depressions in mountainsides.

There is even a physics formula that explains downhill creep. Called diffusional sediment flux, this is calculated as the product of hill-slope and a value called the diffusion constant. Those values multiplied together yields the speed at which a given tombstone (or any physical object on a hill) moves over time. In addition to just modeling tombstone movement, this formula has also recently been used to calculate how erosion rates change with precipitation.

So if we calculated this value for the average tombstone on a hill, it is pretty clear that it will always be gently moving, tombstone owner beneath be damned.

Just in time for Halloween, the spookiest primate tricks the world with a hidden thumb

The aye-aye has been hiding a secret all this time: a sixth pseudodigit

By nomis-simon

Ed: All this week Massive is marking Halloween with stories of scary, witchy, and downright ghastly stories from nature.

The aye-aye (Daubentonia madagascariensis) is an incredibly specialized primate. For one thing, it's the only living representative of its family of lemurs. It also has rodent-like ever-growing incisors and bat-like ears that it uses in combination with an extra-long third digit to tap on trees, listen for the grubs inside, and then extract them with that spindly finger.

And these features make it look pretty creepy. So creepy, in fact, that seeing it is traditionally considered a bad omen or a direct cause of bad luck in its native country, Madagascar.

Given the aye-aye's specialized hand anatomy, it seems like anthropologists would have already investigated that structure pretty thoroughly. But it turns out the aye-aye's hand has been hiding a secret - a sixth pseudodigit!

Frank Vassen on Flickr

In a new study published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, a group of researchers investigated the hand anatomy in one immature and six adult aye-ayes using traditional dissection digital imaging techniques. Like the famous "thumb" of the giant panda, the aye-aye also has a radial sesamoid bone in its wrist that seems to help it compensate for the grasping ability the aye-aye lost when its third digit became specialized for probing out insect larva. Sesamoid bones form within tendons, typically where they cross joints, and the aye-aye's is both enlarged and has muscles attached to it to help it function like a faux-thumb.

This is the first accessory digit found in a primate. By understanding how these different structures integrate in the aye-aye's hand, we may gain further insights into the evolutionary history of the pseudothumb - and the fascinating and endangered aye-aye species.

Climate change threatens bats — and tequila

Climate change could destroy the delicate partnership between agave plants and the bats that pollinate them

Photo credit: Big Bend National Park

Ed: All this week Massive is marking Halloween with stories of scary, witchy, and downright ghastly stories from nature.

Changes in temperature and precipitation associated with climate change alter the habitable ranges for many species. This becomes especially problematic for species that depend on mutualisms — relationships where both species benefit — for existence. Not only are plant-pollinator mutualisms vital for survival of the species involved, they also provide us with numerous economic and cultural services to boot.

We often hear about how climate change threatens bees, our most iconic pollinators, but rarely do we think about the pollinators of the night — bats. Mexican long-nosed bats pollinate the agave plant during their migration from central Mexico to the Southwestern United States every spring — following the blooms of their primary food source. By pollinating the agave, these bats provide us with sweeteners, biofuels, building materials, and most notably tequila.

Photo by Francisco Galarza on Unsplash

Mexican long-nosed bats are currently listed on IUCN Red List as endangered due to habitat loss, agricultural practices, and human disturbance. But a recent study published in Scientific Reports shows that climate change also poses a threat to the already perilous existence of the Mexican long-nosed bat. Researchers found that climate change is poised to reduce the overlap in the suitable range of the agave and the Mexican long-nosed bat by at least 75%, putting this already fragile partnership at risk of disappearance.

As the range for the agave plant shifts to higher elevations and cooler temperatures, this primary food source sustaining the bats during migration will vanish from their route. Maintaining the bats’ migration corridor is key to the preservation of both the partnership between these species and the species themselves; for the tequila and bat lovers out there, it’s non-negotiable.

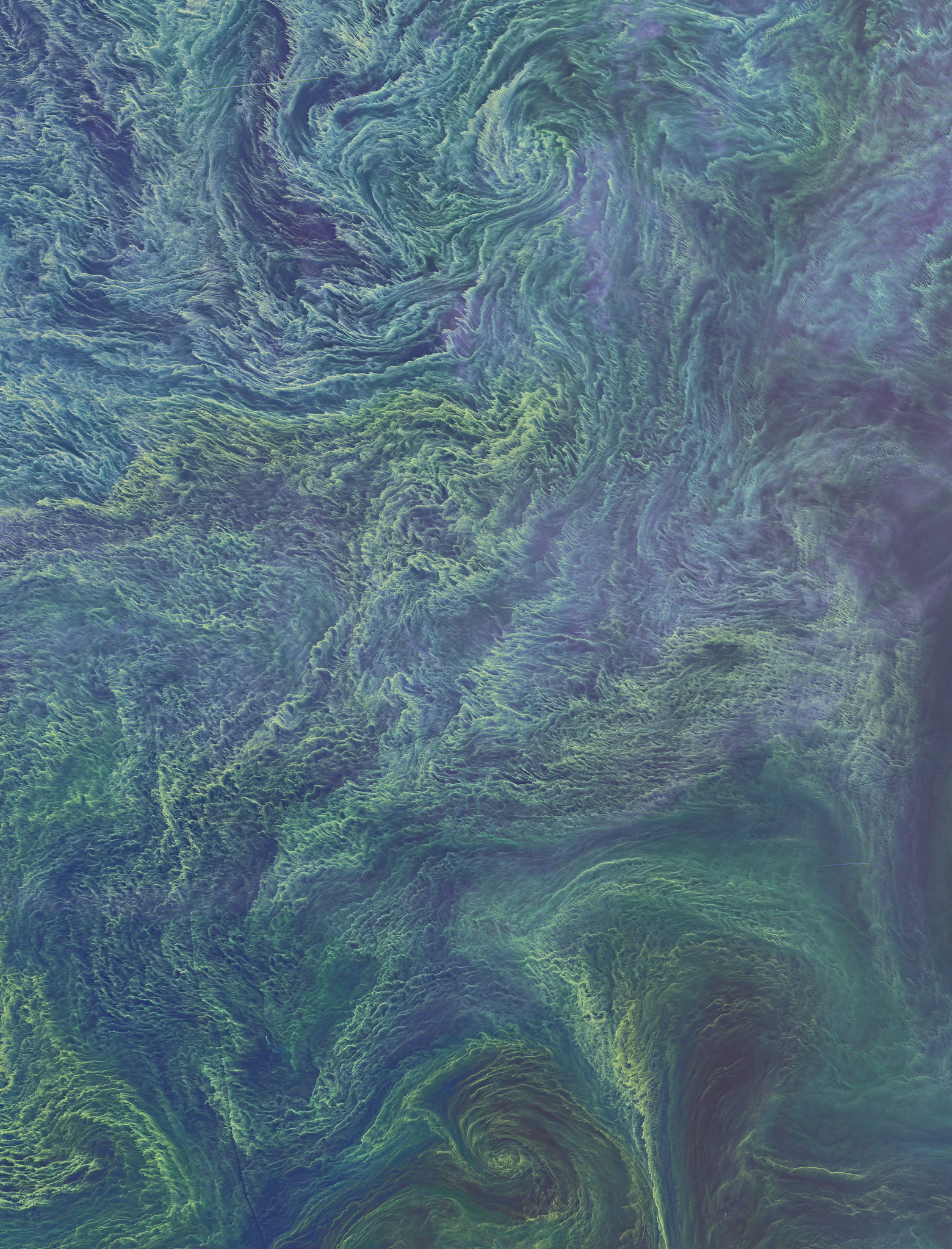

Neurotoxins in the water supply worsen the impact of Zika virus

A neurotoxin produced by cyanobacteria may help explain patterns of Zika-associated microcephaly in Brazil

Photo by Егор Камелев on Unsplash

Zika virus is transmitted by Aedes aegypti — a mosquito that also transmits dengue and yellow fever. In some people, the virus causes symptoms that are very mild. Other cases, however, are dramatic — fetuses that are infected inside the womb can develop microcephaly, a condition in which the baby's head is much smaller than expected. Unfortunately, many cases were reported in Brazil during the recent outbreak of the disease.

The situation motivated Brazilian researchers to search for answers. Some were found quickly: in 2016, a paper described how the virus affects the development of brain organoids. But a big question remained unsolved: why were the microcephaly cases concentrated in northeast Brazil when Zika was spread throughout the country?

Various hypotheses were on the table: folic acid deficiency in pregnant women in northeastern Brazil, coinfection with other mosquito-transmitted viruses, extreme poverty, or even the use of pesticides in agriculture. But nothing seemed to explain why there were so many cases of microcephaly in this particular region.

An interdisciplinary team lead by neuroscientist Stevens Rehen, from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, recently published a preprint that adds one more piece to that puzzle. The group investigated how environmental factors can influence the development of microcephaly.

Northeastern Brazil suffers from drought periods, which can lead to blooms of cyanobacteria. Those microorganisms often produce toxins that can be harmful to human and animal health.

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

The new hypothesis to explain the microcephaly boom in northeast Brazil involved saxitoxin, a neurotoxin produced by the freshwater cyanobacteria Raphidiopsis raciborskii. Perhaps because of a severe drought in the region from 2012 to 2016, there was a higher saxitoxin occurrence in the drinking water supply of northeast Brazil compared to the rest of the country.

In the lab, the team showed that the presence of saxitoxin doubled the cell death rates in progenitor areas of human brain organoids infected by Zika virus. Scientists now believe that this might explain why microcephaly was worse in the northeast region.

Due to the complexity of the Zika outbreak in Brazil, the scientific community had to exercise true detective skills. Scientists had to go beyond their own lab walls and connect different knowledge areas to solve the puzzle. Hopefully, these new findings will help to prevent future cases of Zika-associated microcephaly.

A parasitic flatworm is one of nature's spookiest creatures

Leucochloridium paradoxum is a parasitic flatworm that uses both mind control and mimicry to trick birds into eating it

By FlyNoch.

Ed: All this week Massive is marking Halloween with stories of scary, witchy, and downright ghastly stories from nature.

Larval Leucochloridium paradoxum, more commonly known as the green-banded broodsac, is a parasitic flatworm ingested by snails feeding on bird feces. As the parasite grows, it comes to take over the snail's tentacles, leading to one to two appendages resembling wriggling caterpillars or maggots — known as mimicry.

Mimicry is an umbrella term used to describe when organisms look like other things. For example, insects can look like twigs or leaves to blend in with their surroundings, anglerfish attract prey by wiggling their esca (an adapted spine) to resemble a smaller fish, and some flowers are shaped like female insects to attract males for pollination. L. paradoxum takes mimicry a step further by drawing the snail out into the open to increase its chances of getting gobbled up by a bird.

A land snail with Leucochloridium paradoxum inside its left eye stalk.

By Thomas Hahmann.

Researchers have also found snails infected by L. paradoxum tend to stay in open, better-lit places and on higher vegetation, making them an irresistible snack for birds. Once in the bird, the parasites continue their life cycle, turning into adults, reproducing, and laying eggs. These eggs are released through bird droppings, and the cycle continues!

But the green-banded broodsac is not the only parasite that uses sinister mind control or mimicry to make its way through life. Toxoplasma gondii causes behavioral changes in mice to make cats eat them, and Myrmeconema neotropicum infects worker ants, causing a berry-like blob that will attract birds.

The worst mimicry of all? Raisin cookies that trick me into thinking they're chocolate chip.

Ed again: The views shared by the author in this article do not reflect the cookie-related positions of Massive. We support oatmeal raisin cookies.

Have you ever wondered why it's harder to maintain your weight as you get older?

New research shows that as you age, the rate at which lipids are removed from your fat tissue decreases

Have you ever wondered why athletes often cannot maintain their weight as they get older? Could the culprit be their newly discovered passion for binge-watching while eating fast food? Or could it be that they changed…nothing at all? Interestingly, new research shows that as you get older, the rate at which lipids are removed from your fat tissue decreases, which may explain why maintaining weight is harder as you grow older.

Our white adipose tissue, the main fat-storing tissue in human adults, is one of the main targets when tackling obesity or weight changes. Its size is determined by a phenomenon called lipid turnover – the balance between how much energy your body stores as fat and how much it burns of the stored fat.

This means that, as you age, if you keep that exact same (now not-so-perfect) diet, your lipid uptake will get higher than your lipid removal and you will gain weight.

By Brenda Godinez on Unsplash

Imagine you have a high lipid turnover. Then, the average time lipids spend in your adipose tissue is low. Now imagine you have matched that with the perfect diet. As long as your lipid turnover doesn’t change, your weight will stay the same. The caveat comes with your ever increasing age.

The researchers had been following adults for up to 16 years and continued to measure the lipid turnover of their subcutaneous fat. They discovered that, irrespective of long-term changes in body weight, initial age or even level of exercise, the rate of lipid removal from their fatty tissue was decreasing with age. This means that, as you age, if you keep that exact same (now not-so-perfect) diet, your lipid uptake will get higher than your lipid removal and you will gain weight. In fact, participants who didn’t change their diet during the study period saw their weight increase.

How can you cope with this? To put it simply, the fat that gets stored in your body mainly reflects the amount of food you eat (and not only extra fat, but also extra sugar, gets stored as fat!). Although other factors, such as exercise or the composition of your diet, may eventually also influence fat deposition, this will not alter your rate of lipid removal. So, until other therapeutic approaches come out, we may have to accept that, as we age, we may need to lighten our diets if we want to avoid those extra pounds.

Being reminded of bias makes students treat female professors fairer

Students who read a bias reminder rated their female professors 10% higher

Photo by Mikael Kristenson on Unsplash

Student evaluations help to determine whether professors get hired and promoted. But are they fair to professors? Probably not: multiple studies show that student evaluations are biased against women and people of color.

A new study shows that it may be possible to decrease evaluation bias against female professors by making students aware of the problem.

Researchers tested a method for reducing bias by including a short message about bias in the evaluation forms. This “bias reminder” message explained that evaluations are influenced by students’ unconscious biases about race and gender of instructor. The bias reminder then suggested that students should resist stereotypes about instructors and instead focus on the content of the course.

Photo by Sharon McCutcheon on Unsplash

The researchers tested the effect of this bias reminder in four college courses: two taught by women and two taught by men. For each class, the researchers randomly split the student evaluators into two groups: a control group which received the typical student evaluation and a treatment group which received an identical student evaluation, except that it included a bias reminder.

Researchers found that students who read the bias reminder rated their female professors 10% higher than students in the same class who did not read the bias reminder.

One major limitation of this study is that it only tested the effect of the bias reminder on gender bias. All of the evaluated professors were white. Future studies will need to test the effect of a bias reminder on student evaluations of professors of color.

Increasing diversity among college faculty is an important goal and a complex challenge. However, some changes are easy to make. This study shows that a simple reminder to students could help decrease systemic bias against female professors.

Scientists have created the first-ever 18-carbon ring, a major feat of molecular architecture

They used electric currents and high-resolution microscopes to remove individual oxygen atoms from a larger carbon molecule

Steve Jurvetson on Flickr

Gene manipulation paved the way for a brand-new chapter in science. Could atom manipulation lead to the same revolution? Would it allow us to create new and exotic molecules? Apparently so!

Chemists have been long fascinated by the idea of manipulating carbon atoms and add to the list of carbon allotropes. These type of structures should theoretically exist; however, making them in the chemistry lab has thus far resulted in little success. The main problem is the high reactivity of carbon rings with oxygen, which causes them to quickly undergo chemical reactions and break down into other compounds once they are formed.

But now, chemists at the University of Oxford and the IBM research lab in Switzerland have successfully used an atom manipulation technique to create a new chemical structure fully made of carbon, called a carbon ring.

Engineering the carbon ring was a delicate process. First they created a carbon-oxygen structure, which they laid on a copper plate covered with sodium chloride, or common table salt. Then, they applied an electric current to the structure to remove the oxygen atoms one by one and obtain the circular 18-carbon ring. They did all of this while peering through special high-resolution microscopes that allowed them to see individual atoms, approaches called scanning tunneling and atomic force microscopy.

The carbon ring is called a cyclocarbon, and early analysis has found that this molecule acts as a semiconductor - meaning that it could be very useful in the future as a tiny transistor. More importantly, this new atom manipulation technique may lead to a burst of new research, and potentially the generation of other new molecules.

Genomics has a diversity problem. Here's how scientists are tackling it

At ASHG, researchers are seeing that using only data from white Europeans is leading to incorrect conclusions

Photo by Tim Mossholder on Unsplash

This week, over 8,300 researchers, exhibitors, and journalists arrived in Houston to attend the 2019 American Society of Human Genetics’ (ASHG) Annual Meeting to learn more about cutting edge research in the field of human genetics and genomics. Interestingly, one issue kept popping up throughout the ASHG meeting: the lack of diversity in human genomics research.

This isn’t a new issue.

The human reference genome — the sequence to which all DNA is mapped in reference to — is largely based on individuals of European descent, making it difficult for individuals from under-represented groups to benefit from current progress in genomics. In fact, 70% of the human reference sequence actually originates from a single individual. While this reference genome has helped pushed the field forward, it doesn’t accurately represent our global genomic landscape.

Researchers are aware of this issue — and here’s how they’re tackling diversity in genomics research.

One remarkable effort is being carried out by the Human Hereditary and Health in Africa (H3Africa) consortium, which was launched in 2013 to address the under-representation of African individuals in genomics. H3Africa, with support from the National Institutes of Health, sequenced the entire genome of 426 individuals from 13 different countries, providing a more complete picture of Africa’s genomic diversity.

In the opening ASHG plenary session, Neil Hanchard, assistant professor at the Baylor College of Medicine, shared that this large-scale sequencing effort identified over three million novel single nucleotide variants — which have not yet been observed in current (largely European) genomic databases. For example, surveyed populations from Mali and Botswana had at least 6,000 novel common variants. This concept of "rare" and "common" variants is particularly important since how frequent a variant is in a population is often used to infer pathogenicity (i.e. how damaging it is). The H3Africa consortia’s initial findings show that some previously classified pathogenic variants are in fact not rare and are found in variable frequencies across African genomes.

“This is a starting point,” said Hanchard at the plenary meeting. “African genomes have the potential to inform the [genomics] field more globally.”

In a similar vein, a group of US researchers sequenced over 300 genomes from around the world, including both male and female individuals from different sub populations. By looking at breakpoints and sequence content, the researchers were able to use a technique called de novo assembly to align unique sequences (which previously could not be mapped) to the reference genome, thus constructing a more representative, and detailed, reference genome.

In addition to ongoing efforts like the ambitious All of Us program, these efforts can together help us move towards a future where people everywhere — regardless of their geographic location or ethnicity - will all be able to reap the benefits of human genomics research.

The Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources is unique among international environmental agreements

But that doesn't mean that it's perfect — getting nations to agree requires both formal and informal negotiations

Photo by Derek Oyen on Unsplash

The Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) entered into force in 1982, with the express purpose of ensuring “the conservation of Antarctic marine living resources.” This focus on conservation was revolutionary because other similar international environmental agreements took single-species approaches to regulating fisheries, whereas CCAMLR took an ecosystem-based approach to preserving the Southern Ocean as a whole. In its opening lines, the convention insisted on the “importance of safeguarding the environment and protecting the integrity of the ecosystem of the seas surrounding Antarctica.”

While the text of the convention endorses taking an ecosystem-based approach to protecting Antarctic marine living resources, implementing these principles has been a more gradual process. Initially, CCAMLR focused its attention on immediate concerns such as managing krill fisheries and then in the 1990s on reducing illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing within the Antarctic. In the last two decades, however, CCAMLR members have sought to more fully implement the holistic management principles articulated in the early 1980s by establishing a representative network of marine protected areas (MPAs), with two major successes: the designation of the South Orkney Islands Southern Shelf and the Ross Sea Region MPAs.

Despite these successes, other threats remain. In particular, some member countries have sought to advance their own agenda and engage in unrestricted fishing by reinterpreting the Convention and downplaying its roots as a conservation instrument. While the Convention’s definition of ‘conservation’ does include ‘rational use,’ it so strongly lays out the limited circumstances under which fishing may take place that this further highlights the intent of the original architects of the agreement, who intended for it to be a conservation-oriented instrument consistent with the principles of the Antarctic Treaty System. These efforts to undermine the convention have not gone unnoticed, and other parties have pushed back to ensure that CCAMLR remains able to protect the Southern Ocean ecosystem.

Hammering out international environmental agreements and keeping them up to date is no easy task, and one that I explain more in a new paper, published in Aquatic Conservation. It examines the process of reaching consensus on proposed conservation measures to better understand the role of informal and external drivers in establishing large-scale networks of MPAs. Based on these insights, I also outline a series of recommendations for transboundary conservation efforts, which are likely to become increasingly more important as we tackle climate change and other large environmental issues.

Vaccine-laced snacks are being scattered in the wilderness to protect wildlife from rabies

700,000 oral rabies vaccine baits are being distributed in southwest Virginia this fall

Photo by Quinten de Graaf on Unsplash

While rabies is relatively rare in humans in the United States, it's much more common in wildlife like raccoons, skunks, and bats. In fact, rabid raccoons have been identified in every state along the Atlantic coast. Since no wild raccoon wants to be trapped and stuck with a needle, the vaccines are instead put into baits, which the raccoons find and eat. Now, scientists and wildlife managers in Virginia are distributing a vaccine for raccoons that could prevent them from getting rabies. These baits have been used in the United States in one form or another since the 1990’s in foxes and coyotes as well as raccoons — but the project only recently came to southwest Virginia.

U.S. Department of Agriculture

Although rabid animals are found across the country, so far raccoon rabies is limited to the Eastern Seaboard, and wildlife managers are hoping to use these vaccines to make sure it stays that way. Rabies is a pretty scary disease, so limiting its spread is extremely important. Symptoms, which may not develop for weeks or months after a bite from an infected animal, start off seeming like the flu — a fever, chills, muscle weakness, a headache — but quickly get much worse. The rabies virus attacks the brain and nervous system, and as the disease progresses patients may have anxiety, confusion, psychotic symptoms, a fear of water, and sometimes paralysis before they fall into a coma and die.

Most residents of first-world nations with advanced medical systems rarely worry about rabies because vaccines are readily available for both them and their pets. However, rabies remains a significant threat worldwide, particularly in rural areas of the Global South. Every year more than 59,000 people die from rabies, about half of whom are children under the age of fifteen. Globally, 99 percent of human cases are caused by contact with rabid dogs. Although they have not yet been widely implemented, studies on similar vaccinated baits have shown promise in combating rabies in dogs and thus in reducing risk to humans.

Meet the friendly vampire bat: they drink blood, cuddle and even groom fellow bats

Researchers tried to understand what motivates vampire bats to do nice things, like grooming each other

Vampire bats (Desmodus rotundus) do drink blood, which can be off-putting. However, vampire bats are also very cuddly, at least with one another. Female bats cluster together for warmth, share food, and groom their cuddle-mates by licking each other’s fur. Being groomed can reduce stress, lower heart rate, and promote cooperation.

It’s clear that bats benefit from being groomed, but not why others volunteer to be the groomer. Bat grooming often prompts animal behavior researchers to ask: why do animals do nice things, like grooming?

To study when bats are willing to groom one another, researchers at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute set up two tests for a colony of female vampire bat. In the first test, scientists rubbed water on the fur of each bats’ back, and then measured the amount of time each wet bat spent being groomed by other bats.

As expected, bats were groomed more after getting wet. So, it appears that vampire bats will help out a friend in need. However, the second test showed that groomers weren’t only motivated by helping one another.

A vampire bat in action.

By Uwe Schmidt

In the second test, scientists grouped a few female bats in clear cages for 30 minutes at a time, watching for each moment when one bat groomed another. The scientists noted what was happening just before each grooming event to measure how often the bats were grooming themselves before leaning over to spare a lick for a friend.

The researchers found that one bat is most likely to groom another if the groomer has just been grooming herself. In short, some bats agree to groom others just because they like to lick. Perhaps the act of grooming reduces anxiety, just as being groomed does.

Studying the details of how animals cooperate is useful for understanding how social groups stay together in nature. For vampire bats, grooming isn’t all about utilitarianism or the fear of punishment. Sometimes, bats groom because they want to.

A catastrophic power outage darkens California while horny spiders invade

Tarantulas, fire-inducing weather, and failing infrastructure make for a spooky October story

Photo by Christos Politis on Unsplash

I saw a tweet the other day that sent chills up my spine.

I'm a field biologist, so I've spent plenty of time in the company of creepy crawlies, and I wouldn't call myself an arachnophobe, but something about sitting in a room where the lights have been shut off to prevent massive fires driven by a climate change-induced drought surrounded by migrating tarantulas sounds like my "The Day After Tomorrow" nightmare.

The mass tarantula migration is actually the least worrisome part of this story. Male tarantulas across the western part of the United States are migrating right now in search of mates. Tarantulas, with their huge, hairy bodies, look intimidating, but actually are not dangerous to humans. They have intricate courtship rituals that occasionally end up with the male as a meal instead of just a mate. And although this year's migration is slightly larger than it usually is, this is a normal phenomenon that happens from about mid-August to mid-October each year. Even if you (understandably) don't want to share your space with these eight-legged furballs, experts say that if you spot one you should just leave it alone.

But something much more frightening than migrating tarantulas is happening in California at the same time. Pacific Gas and Electric Co. (PG&E), the main power company for much of the heavily-populated Bay Area, has shut off power to 800,000 customers in the region in the face of a red-flag wildfire and wind warning. High winds and increasingly dry weather caused by climate change mean that the entire area is — again — at risk of going up in flames.

And this lack of preparation is, on some level, just a combination of greed, incompetence, and willful disregard for the environment. PG&E was found responsible for last year's deadly Camp Fire in Paradise, California, after faulty power lines sparked the blaze. And in April, the company was admonished by a judge for paying out shareholder dividends instead of trimming trees around dangerous lines. Now a large portion of California residents are paying the price as they spend unknown amounts of time in darkness.

U.S. infrastructure is simply not prepared for climate change. Hundreds of thousands in California are now reaping the whirlwind of that inaction. PG&E's sloth and ignorance put people, particularly those that rely on electricity for medical devices, in grave danger. There's many horrifying aspects of this story, but the one that stands out to me is that the only backup plan for people who need power for life sustaining medical equipment is for them to call an ambulance (presumably on their own dime).

As many have said time and time again, the most vulnerable among us will be the first to experience — and are already experiencing — the impacts of climate change. People are going to suffer and die, and it won't just happen in huge dramatic ways like hurricanes and drought. It'll happen in lots of mundane, insidious, and unnecessary ways. Like not having access to electricity to power a breathing machine, or not having an air conditioner during a heat wave.

So by comparison I'm fine with the tarantulas.

Fact check: Those red blobs aren’t oxytocin

An amazing image has been making the rounds on social media, but the researcher who created it has set the record straight on what it shows

Photo by Luma Pimentel on Unsplash

In 2015 MIT cognitive neuroscientist Dr. Rebecca Saxe took a magnetic resonance image (MRI) of herself kissing her son, the first of its kind in the world. Writing about the experience for Smithsonian Magazine, Dr. Saxe said that she and her collaborators took the image “because we wanted to see it.” This arresting image, the MRI Mother and Child [you can see it at the Smithsonian link above], is both extremely modern, captured with cutting edge technology, and timeless in its imagery.

Now, four years later, a version of the image with red blobs lighting up the brains of both the Mother and Child, has gone viral again. Some posts about the image falsely conclude that the bright colors reflect the biology of the parent-child bond, mainly the release of hormones like oxytocin (the so-called ‘love’ hormone). Recently, Dr. Saxe took to Twitter to set the record straight.

The ‘blobs’ in the image aren’t hormonal at all, but are results from a scientific study on how infant brains process visual information conducted by Dr. Saxe herself. The colors on the image reflect parts of the brain that used more oxygen (in that actual infant and mother) while viewing faces compared to oxygen use in brains viewing natural scenes. In fact, there isn’t yet any way to directly measure the release of oxytocin or its levels in the brains of living humans. The closest we can come is to measure its levels in blood or saliva, or to measure how brain activity changes when we give someone oxytocin. Developing methods to measure oxytocin in human brains is an area of active research, but it will probably be many years until we’ll be able to use them to study infants.

You should wash your rice to reduce heavy metal contamination

Yes, washing rice involves sacrificing some of its nutritional value, but it also reduces the level of heavy metals present

Photo by Pille-Riin Priske on Unsplash

Have you ever wondered why you wash your rice — or soak it overnight — before cooking it? Perhaps you wash your rice grains to enhance taste, reduce starch levels, or maybe that's just the way your family has always prepped rice. Thanks to a tip from science communicator Samantha Yammine — who came across Dr. Nausheen Sadiq's neat finding while live-tweeting a forum on Diversity and Excellence in Science — it turns out there is another reason why, as washing rice actually helps reduce the concentration of heavy metals, like chromium, cadmium, arsenic, and lead.

Heavy metal contamination in crops can be caused by human activities, such as mining, fertilizers, pesticides, and sewage sludge. Compared to most cereal crops though, rice (Oryza sativa L.) actually accumulates more heavy materials, like cadmium or arsenic, where long-term heavy metal intake can cause health risks. For example, long-term arsenic exposure leads to skin disease, high blood pressure, and neurological effects. This is especially important to consider as rice is a staple food across the globe.

Heavy metal contamination in crops can be caused by human activities, such as mining, fertilizers, pesticides, and sewage sludge.

Photo by TUAN ANH TRAN on Unsplash

In a recent study, researchers investigated the effects of different cooking methods (normal, high-pressure and microwave cooking) on the concentration, bio-accessibility and health risks posed by three heavy metals (cadmium, arsenic and lead) in two strains of brown rice. After cooking 100 grams of brown rice grains, researchers evaluated bioaccessibility (i.e. how much of the heavy metal is released for absorption) by mixing rice samples with simulated gastric fluid, and then used spectrometery to measure heavy metal concentration. Lastly, the researchers calculated the health risk posed by the heavy metals by calculating values such as the average daily dose.

Overall, the researchers found that instead of the three different cooking methods, it was the washing process which significantly reduced concentrations of cadmium, arsenic and lead, suggesting that the reduction may be due to rice morphology. For example, lead is found largely in the outer compartments of rice kernels, so lead is more likely to be removed during rice washing.

In contrast, the three cooking methods did impact bioaccessibility i.e. how much of the heavy metal would be released for absorption by the body. Here, washing and soaking isn't enough as rice absorbs water poorly at 25°C. This finding was also reflected in calculated values: the average daily doses of cadmium, arsenic and lead were lower in washed and cooked rice, compared to raw rice.

It's worth noting that the European Commission has enforced limits on heavy metal levels - for example, arsenic is currently limited to 200 parts per billion (ppb) for adults and 100 ppb for infants. Both the U.S. and Canada currently have no limits in place for arsenic in food — though Canada is currently reviewing a proposal to add maximum levels for arsenic found in white and brown rice, while the U.S. FDA has previously released a (non-binding) risk assessment, suggesting the same 100 ppb levels as Europe.

So the takeaway here is that yes, your family and all those professional chefs have been right all along. Yes, washing rice involves sacrificing some of its nutritional value, but doing so means you can reduce the levels of heavy metals present in grains, and still enjoy dishes like rice cakes. And returning back to Yammine's reporting, Saudiq actually shared that by soaking and washing rice for ~5 mins, you can get rid of 50-100% of these elements. (Thanks Sam!)

Meet the colour-changing green forester moth: a living water vapour sensor

Researchers used microscopy techniques to understand how the green forester moth changes from a shiny green to a rusty red colour

Charles James Sharp (Sharp Photography)

We often think of moths as boring and plain, especially in comparison to their more colorful siblings, the butterflies. However, moths can be just as colorful, and the green forester moth (Adscita statices), with its shiny green body and wings, is a great example of this. But this particular moth doesn’t always have its brilliant green colour. In fact, if you were to spot it early in the morning, it might have a rusty red color. It changes its color to green during the day and when night falls, the green forester moth will turn red again.

In a new study, researchers from the University of Fribourg and Lund University investigated this curious phenomenon. They used electron microscopy to look at what the tiny scales on the green forester's wings are made of, and a combination of microscopy techniques and optical modelling to figure out how the moth achieves this colour change.

The researchers found that the moth wing scales contain a pigment which gives them their colour, like in many other insects. Interestingly, the green forester moth has two distinct types of scales: black ground scales, and coloured cover scales which have minuscule holes (50-300 nm wide) in the scales that can take up water. When these holes in the scales fill with water, it causes a distortion of the light and turns the moth from green to a rusty red. Because of this dynamic colour changing, the researchers have dubbed these moths ‘living water vapour sensors.’

_ventral.jpg)

Charles James Sharp (Sharp Photography).

This ability allows the moths to be camouflaged in the morning and evening using the red colour in its native habitats, such as the reddish brown stems of meadow plants. On the other hand, the green colour both signals to birds that the moth is poisonous, and to potential mates that they are a good mate choice. However, it does come at a cost. The water vapour that gets trapped in the wings will make the moths heavier and will therefore make flying harder.

How exactly the moth evolved this humidity-dependent colour-changing ability — despite it causing problems for flying — is still an open question to be answered by the scientists.

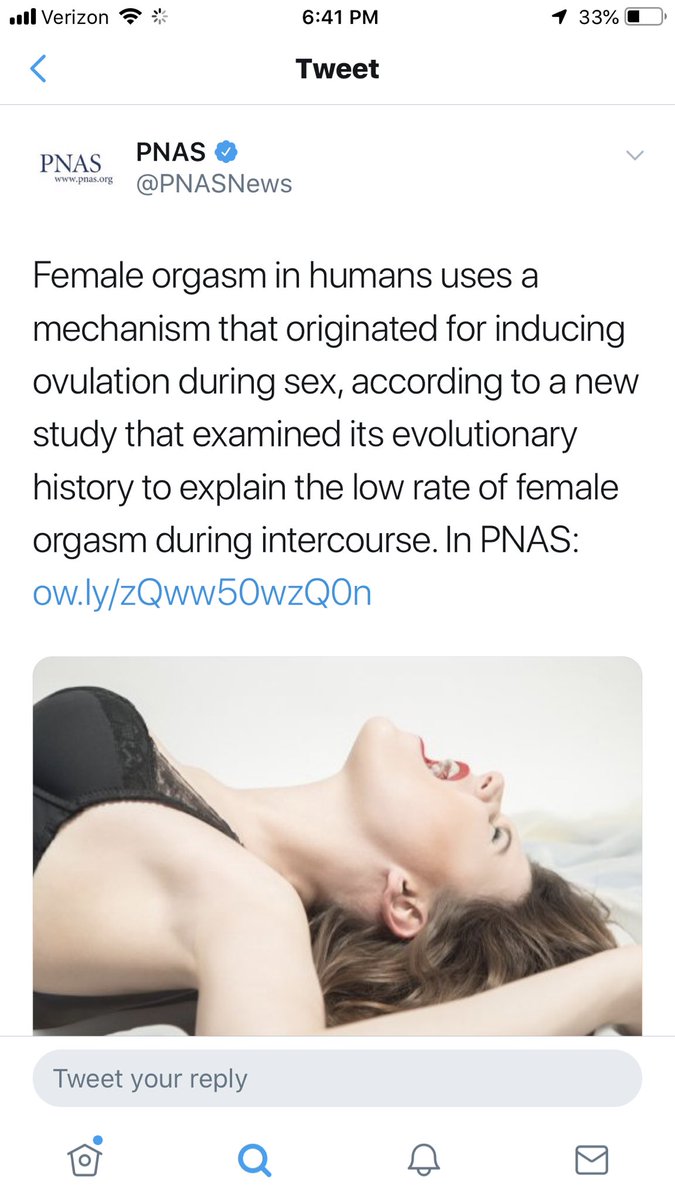

Scientists and journalists are furious at how PNAS promoted a recent study on female orgasms

What makes matters worse is that the study was done IN RABBITS!

By Eliza Diamond on Unsplash

A recent study in the journal PNAS injected rabbits with hormones to look at a potential link between the female orgasm and ovulation. The stock images (as seen below) used to promote the study had scientists and journalists up in arms on Twitter.

A screenshot of how PNAS used stock images to promote a recent study.

Twitter: @JNRutherford

I'll let the tweets speak for themselves:

On 6th October (9:24 PM EST), the PNAS journal offered an apology and took down the offending tweets.

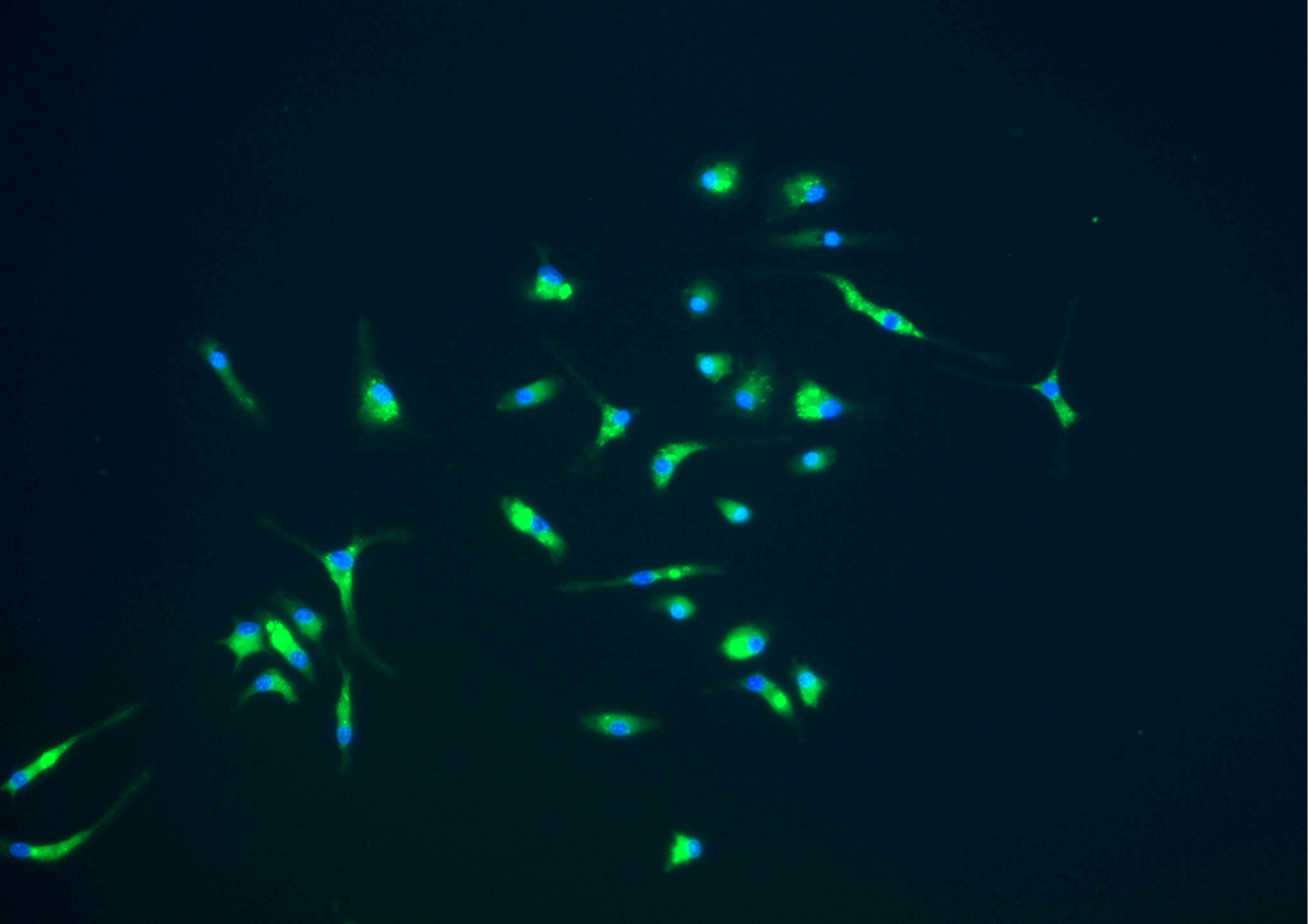

Certain vaginal bacteria could help protect women from STIs

Some species of Lactobacillus appear to be protective against chlamydia

Photo by Christopher Boswell on Unsplash

Reports of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) like chlamydia are on the rise. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), chlamydia is the most common notifiable disease in the U.S., and among the most prevalent of all STIs in the world.

STIs are a serious public health matter, and chlamydia in particular is associated with a host of devastating burdens to individuals and society as a whole. Patients with chlamydia often do not present clinical symptoms, a dangerous feature of this infection, as untreated cases of chlamydia can lead to serious health outcomes for young women, including pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy and infertility. It has been reported that this inflammatory condition may facilitate other infections such as HIV.

Exactly how the cervicovaginal microbiome (the microbial community in an individual's cervix and vagina) might affect a woman's susceptibility to STIs is poorly understood. But, a type of bacteria called Lactobacillus are thought to play a protective role in the cervicovaginal environment. Researchers from the University of Maryland School of Medicine set out to understand the relationship between host and vaginal microbiome in an effort to identify how Lactobacillus might protect a woman from contracting chlamydia.

Photo by Louis Reed on Unsplash

They found that Lactobacillus species that produced a specific shape of lactic acid molecule (called an isomer, in this case called D(−) lactic acid) were associated with protection against chlamydia and lower epithelial cell proliferation rates. One specific type of this bacteria, Lactobacillus iners, that did not produce D(-) lactic acid also provided little protection against chlamydia.

Our immune systems and microbiomes work hard to protect us from infection, and this paper is a great reminder of that. Further research is needed to improve our understanding of the role of the cervicovaginal microbiota in protection against STIs. This understanding could help us develop therapeutic strategies to minimize the burden of STIs and improve women’s health.

Out in the jungle, looking for a cave? Machine learning and lasers can help

New techniques are helping field researchers locate hard-to-spot caves

Gabriela Serrato Marks

In densely vegetated tropical forests, caves can be incredibly difficult to find. The entrances are sometimes tiny, just big enough to squeeze into, or covered with branches and leaves. Even when you have exact GPS coordinates, caves that haven’t been visited in a while can blend into the rest of the environment.

Leila Donn (orange and blue gear) with other researchers walking past a cave wall.

Gabriela Serrato Marks

That means that it’s particularly difficult to find unmapped caves. Unfortunately, those undisturbed caves can also be the best places to find geological or archeological samples. That’s why Leila Donn, a graduate student at University of Texas - Austin, is trying to find a better way to search for caves. We first met last year, when we went caving in Belize. She’s a great caver because she is an accomplished rock climber, knowledgeable geologist, and pretty much completely fearless. I wasn’t at all surprised to hear that she had been finding caves in Belize that hadn’t been visited by humans for centuries.

Although you may think that geologists just go out to the field with rock hammers and whack stuff, Donn’s work is extremely computational — she’s using machine learning to find the unmapped caves. Her approach combines LiDAR images (using lasers to create 3D maps) with other information about the terrain, like slope and distance to streams. Though the research hasn’t been peer reviewed yet, it has been tested (cave reviewed?): she successfully used the machine learning to find caves and sinkholes during a summer of ground-truthing.

Stalactites and stalagmites.

Gabriela Serrato Marks

Now that Donn knows her algorithm works, she’s going to add more training data and expand her analysis area. In the future, this research could be used to find more caves, but also to better manage wide swaths of forested areas.