Photo by Vlad Kutepov on Unsplash

Bats' unique immune systems make them stealthy viral reservoirs

These ecologically important animals have been at the center of many major viral outbreaks, and we are beginning to understand why

In 2001, Nipah virus emerged in India, causing an estimated 66 cases and 45 deaths after people unknowingly drank contaminated raw date palm sap. In 2002, SARS (a coronavirus termed Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) arose in Asia, resulting in 8,000 infections and almost 800 deaths globally. And from 2014-2016, the Ebola virus outbreak shocked the world, sickening over 28,000 people and killing over 11,000 across Africa.

Coronaviruses (a family of closely related respiratory viruses) have now made headlines again, in the form of 2019-nCoV, the new coronavirus that emerged in Wuhan, China. As of February 2nd, there have been 14,564 cases and 305 deaths from 2019-nCoV, with cases confirmed in 25 countries. All of these alarming outbreaks have one intriguing factor in common: bats.

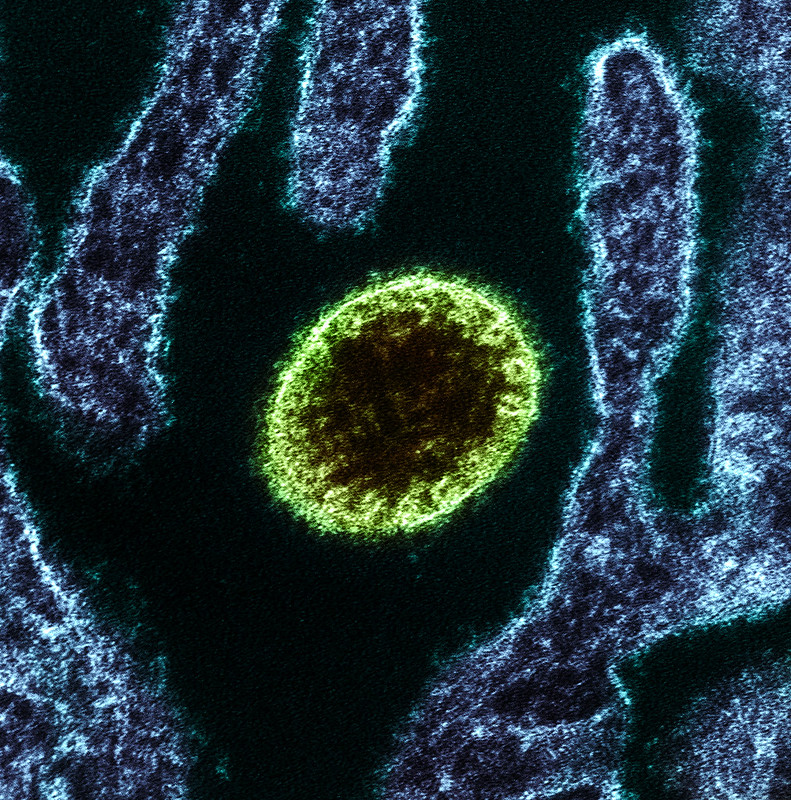

Nipah virus is one example of a bat-borne disease that can spill over into humans

NIAID on Flickr

We have known for quite some time that bats were the primary source of both the SARS epidemic and the Nipah virus. The Ebola virus also originates in fruit bats, which can infect other forest animals who then pass the virus to humans. And evidence strongly suggests that bats have played this same role – which scientists term the "reservoir species" – in the coronavirus outbreak. There are over 1,300 known species of bats, making them the second largest group of mammals on Earth. But their strange immune systems that make them the reservoir species for so many viruses are what make them truly special.

Humans aren't constantly exercising; we jog, or work out for a bit, but then we stop. As a result, unless we are very sick, our body temperature stays around 36.4 degrees Celsius. If we do have a fever, that stimulates an inflammatory response, and our immune system quickly kicks into action, eliminating the foreign pathogen from our bodies. However, bats are constantly exercising: they fly, which increases body temperature and metabolic rate. This led scientists to come up with an initial theory as to why bats have a strange immune system, known as the "Flight as Fever" hypothesis. Because bats' bodies are often put into what, for humans, is a "fever" state, they may be more resistant to viral damage, allowing them to become symptom-less carriers of viral disease.

In a recent review, virologist Arinjay Banjeree and colleagues summarized the immunological differences between bats and humans to uncover why these animals make such effective viral reservoirs. The first difference they noted was interferon levels. Interferons (IFNs) are an immune substance animals secrete to eliminate viruses. Humans have them, and so do bats. When grown in labs, analysis showed that bat cell lines produce higher levels of type I IFNs than human cell lines. Type I IFN is responsible for a variety of anti-viral jobs including limiting viral replication, killing infected cells, and activating other immune cells. Though wild bats have been shown to carry high IFN levels as well, the link between bat cell line behavior in the lab and bat's natural immune system needs more work.

There's more strangeness, on top of their high interferon levels and flight-induced fevers. A study on Big Brown Bats revealed that bats have lower levels of inflammatory cytokines in their blood than we do. Inflammatory cytokines are substances in our bodies that race to the site of an infection, bringing immune cells with them, which helps to quench it locally before it can spread. This allows infected bats to keep spreading diseases to other animals without becoming victims themselves.

Bats are ecologically important and fascinating animals, but we must be conscious of limiting human-bat interactions to stop the spread of diseases

Environmental stressors – such as drought or extreme temperatures – can increase the rate at which bats pass diseases to humans. Not only does stress in general tend to reduce animals' immune functions, but stressors such as shortages of food or water can force bats to migrate, spreading disease further. In fact, a recent "spillover" (the passing of a virus from a reservoir species into a new host) of Hendra virus from fruit bats in Australia correlated with a food shortage for local bats due to a climate shift. Because the bats were under nutritional stress, they were more infectious, which coincided with their moving into new territories in search of food. This created a perfect storm of new hosts and infectious reservoirs, resulting in an outbreak of Hendra among horses.

Attempts to study bat immune cells in the lab haven't made much progress. Many bats do not develop the symptoms of the viral diseases they carry, and when they do, attempts to culture their cells in the lab have been unsuccessful (essentially, the cells cannot survive in a laboratory environment, and they die). In 2018, a Gammaherpesvirus was isolated from Big Brown Bats and maintained in tissue culture, representing a huge leap forward in bat-virology research. However, progress has been slow and restricted to just a few cells types from a few species of bats.

With the great diversity in bat species, their unique immune adaptations that support asymptomatic carriage of viral diseases, and the fact that bats are in close contact with humans around the world, it is no great surprise that bat-borne diseases have followed humans throughout history. From Ebola to herpes, bats represent a reservoir for a number of devastating diseases and viral outbreaks due to these animals is likely to continue increasing. With so much left to learn and discover about these little creatures, it's no wonder they remain at the forefront of human health headlines.

Hi Marnie: great job on this! I have one question about the ‘Flight as Fever’ hypothesis. If all the systems in the bat allow them to clear viruses (more IFN, uninhabitable temperstures etc) how does the virus persist? Something like the gammaherpesvirus makes sense because it can go into latency or ‘hide’ but for ebola, coronaviruses, hendra virus etc they can’t do that. So the bat is built to clear viruses more efficiently, how does that coincide with their ability to pass viruses along?