Lead poisoning hits low-income children harder than their affluent neighbors

Children living in poverty suffer greater cognitive and physical effects from lead exposure than children from richer families, even if they live in the same area

In 1904, John Lockhart Gibson, an Australian ophthalmologist, published a study blaming lead present in paint as the reason for impaired eye motion and sight in children. More than 100 years later, lead is now known as one of the most toxic and harmful environmental insults to humans, particularly to children. A new study published in Nature Medicine on Monday shows that two factors — lead exposure and poverty — may be interacting to further impair cognition and brain development in children.

Ayratayrat on Wikimedia Commons

Lead accumulation leads to lead poisoning, which can include symptoms like abdominal pain, headache, anemia, kidney dysfunction, and memory problems in adults. But, unfortunately, as Gibson saw a century ago, the highest risk of lead poisoning falls on children. Children’s growing bodies absorb more lead and, due to their exploratory nature, they tend to come into contact more with their surroundings, which potentially exposes them more.

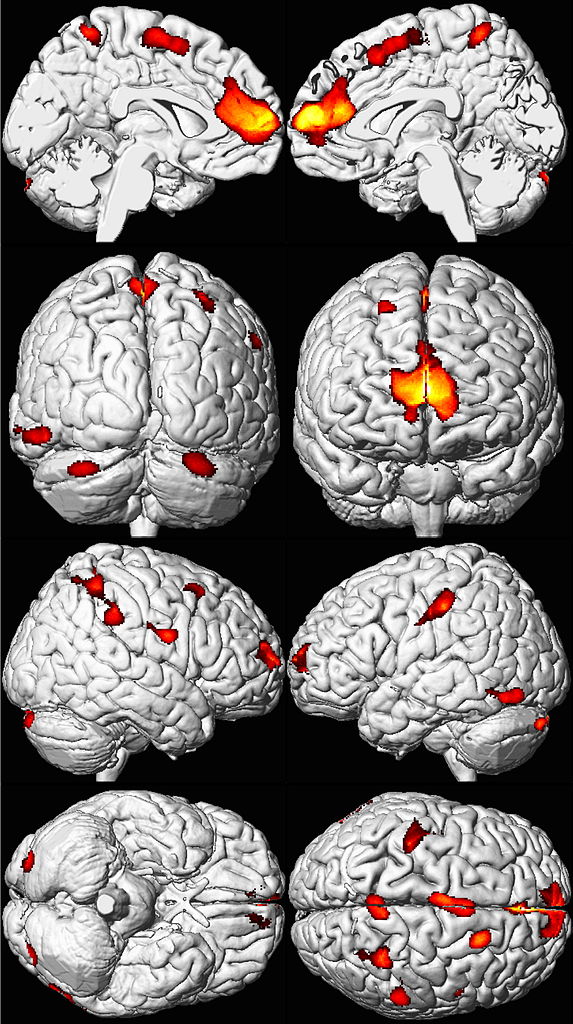

Lead poisoning in children sets off a cascade of negative behavioral outcomes and intellectual disabilities, all linked to brain development. Adults who were exposed to lead during their childhood have decreased brain volume, specifically in areas that are in charge of executive functions and decision-making such as the prefrontal cortex.

However, other factors also affect brain development, among them socioeconomic status. For example, socioeconomic status plays an important role in determining cognitive performance in children.

The study, led by Elizabeth Sowell, Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Southern California, used data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, one of the largest studies of childhood brain development. From this data, they obtained demographic, cognitive testing, and brain imaging data from 9,712 children nine to 10 years of age across 21 different sites in the United States.

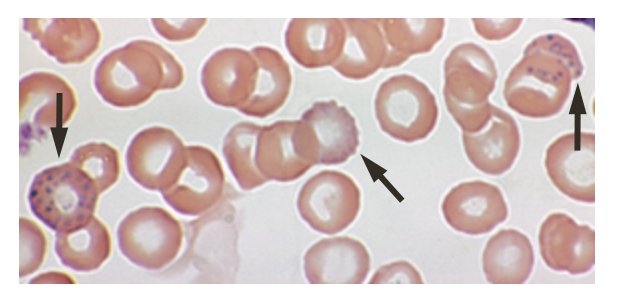

"Stippling" (indicated by arrows) of red blood cells suggests toxic lead exposure.

H.L. Fred and H.A. van Dijk, via Wikimedia Commons

The goal of the study was to examine how socioeconomic status, in this case family income, played a role in determining cognitive performance and brain development in light of exposure to lead. Unfortunately, this dataset does not contain information on the blood lead levels present in the children. For this reason, the authors calculated a "lead risk score" based on residential census tracts which predicts the risk that the children were exposed to lead throughout their lifetime based on where they lived. Although the authors used a proxy for actual blood lead levels, the lead risk score they calculated significantly associates with the average blood lead levels seen in that particular area, suggesting it works as a good substitute.

The study replicated previous findings that show that children from the low-income group have lower cognitive test scores than children from middle or high-income families. The authors also examined brain imaging data, looking at the thickness, surface area, and volume of the cortex, the outer layer of the brain responsible for many higher-order functions. They found that children from low-income families had decreased cortical area and volume.

In previous study, childhood lead exposure was correlated with a significant loss in brain volume in the areas highlighted in red and yellow.

K.D. Cecil et al., 2008 in PLoS One

However, what was most interesting about this study was that they found a negative association between lead risk and cognitive test scores and brain morphology — but only in the low-income group. With increasing risk of lead exposure, cognitive test scores and brain volume decreased. The analysis revealed that there was an interaction between lead exposure and family income that determined worse outcomes of cognitive testing and brain structure in children.

Children from low-income families living in high-risk areas had lower cognitive test scores and smaller cortical volume than children from high-income families living in the same areas. Although these differences between low and high-income children were also present in areas that had a low risk of lead exposure, they were not as dramatic, meaning that poverty worsens the effects of lead exposure on the brains and behavior of children.

This suggests that children from low-income families may be more susceptible to toxic environmental hazards such as lead exposure and that children from higher-income families may be protected.

Recently, health and environmental agencies have attempted to significantly curtail exposure to lead by setting important limits. For example, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) set the baseline of “elevated” blood lead levels for children to 5 micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood (μg/dL), decreasing from the previous value of blood lead level of "concern" of 10 μg/dL.

In spite of more regulations, poor governmental decisions continue to plague low-income communities. One important case of lead exposure is the Flint water crisis. In 2014, the city of Flint, Michigan, changed its water source and began to obtain its water from the Flint River in a move meant to save money. With this change, came undrinkable, foul-smelling water and disease. Flint residents complained about water quality, but their objections fell on deaf ears.

Only after Virginia Tech researchers started testing the water and proving that lead levels were much higher than normal, did government officials take action. But it may have been too late. Elevated blood lead levels were found in 4.9% of children in comparison to 2.4% prior to the water source change. Children from disadvantaged neighborhoods had the greatest blood lead level increases.

This new study is important to cities like Flint, where approximately 40% of residents live in poverty. As of now, we do not know how lead exposure will affect Flint's children, particularly those in low-income communities. Seeing as there exist socioeconomic disparities in toxic exposure to lead and other environmental pollutants in the United States, more studies need to be done to assess how these factors interact to affect brain and behavior in children in response to toxic insults. Further, using these results, it is imperative to address lead poisoning by implementing policies that have these vulnerable communities at the center.

Lead exposure in low income areas is definitely something that has hit the media recently, as succinctly put in the article, as in during the Flint lead contamination case. However, Claudia takes this one step further, suggesting evidence recently found that low income children in the same area as high income children are more affected by environmental lead contamination. What an interesting find, and something desperately needing more research. A well laid-out piece with great real-world examples, highlighting a finding that I believe is the tip of the iceberg on this research.